The pipeline wars in South Caucasus and Georgia

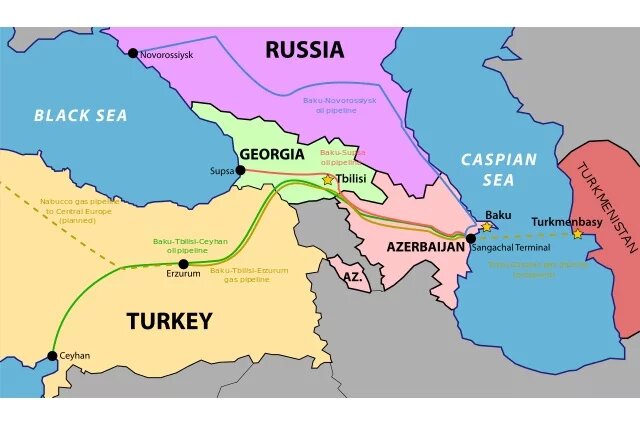

Georgia's unique location at a strategically important crossroads makes it a country of key geopolitical interest to Russia, Turkey, USA and the EU. It is located in a region known for its volatility due to the existing ethnic, religious, political and military tensions after the collapse of the Soviet Union.[1] Neighbouring Azerbaijan holds part of the vast Caspian energy resources that constitute around 3-4 % of the world reserves. Driven by US and EU special interests, Azerbaijan managed to establish a transit route for energy resources to the Black Sea and on to the Mediterranean bypassing Russia.Georgia has become an essential part of Caspian energy transit architecture, hosting sections of two major pipelines: Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) and Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum. For the US and EU Georgia “matters because of its importance as a transit route for energy goods from the Caspian Sea region”.[2]

The new route has been recognized as “destructive” for Russia’s South Caucasus policy as it undermines Russia’s ambitious goals of monopolizing hydrocarbon routes from East to West and expanding its influence towards the Middle East. Oil and gas revenues represent almost half of Russia’s budget, and have allowed it to rebuild and grow during the last decade, increasing its ambitions to change the rules of the game on a global scale. The energy sector is more than just a commercial asset - it is one of the pillars of Russia’s stabilization and its own political influence in the world.[3] This is why Russia has even physically attacked energy infrastructure that goes against its interests. During the August 2008 war with Georgia, it bombed the Baku-Supsa and Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipelines. Later, in 2015, South Ossetia, a Russian-backed separatist region, expanded its de facto border deeper into Georgian territory, taking over a short section of the Baku-Supsa pipeline that brings oil to the Black Sea Coast. [4]

After the Ukrainian gas crisis in 2006 and the 2008 war, the EU was forced to seek ways to diversify its energy resources and reduce its dependence on Russia's state energy company Gazprom. New elements in the energy market like shale gas, green energy or even the EU’s Third Energy Package – were used by member countries to combat Gazprom’s monopoly over their internal markets. The concept of a Southern Gas Corridor, a “project of European interest”,[5] connecting the countries of the Caspian Sea and the Middle East to the EU by long natural gas pipelines, posed a threat to Russia's monopoly over the EU’s gas market. Russia responded with a number of projects of its own, including the "Blue Stream" pipeline leading first to Bulgaria and then Turkey, whom it considered an energy ally until late 2015.[6]

For Georgia, integration with the EU and Euro-Atlantic structures has served as a red line in all political negotiations. In 2013 Russia heavily pressured Armenia, Georgia and Ukraine not to sign the Association Agreement with EU. Despite pressures such as an accelerated "border" demarcation process around South Ossetia, Georgia signed its Agreement in 2014.[7] It is expected that the country will join the European Energy Community in 2016. This will allow Georgia, in case of Russia’s illicit acts in occupied territories to respond to Russia through the European Energy Community.

Falling Oil Prices

EU and US political and economic sanctions against Russia over its annexation of Crimea coincided with the drop in oil prices that contributed to the economic and financial crisis in Russia. Since June 2014 the global oil price has fallen more than 70 per cent. It has also had a dramatic impact on Azerbaijan. Georgia benefits from savings on oil imports, which fuels economic growth, but low oil prices also have had a negative spillover effect on a country‘s economy. Exports to Russia, Azerbaijan and Armenia have fallen by almost 50 per cent, while remittances from Russia have decreased by as much as 40 %.

Oil prices fell due to the doubled US oil production in the last six years and the steady rise of production by Canada and Iraq. All of that forced traditional suppliers as Saudi Arabia, Nigeria and Algeria to seek new markets for their oil and reduce their prices. Demand in the EU, as well as China, Brazil and India fell significantly due to the slow economic growth and improved energy efficiency. The lifting of sanctions against Iran and the Islamic Republic's return to the international oil market also facilitated the oil glut, which is expected to continue until 2021 unless oil production is halved.

Contrary to expectations that low oil prices would decrease investment in renewables, investments in renewable energy hit of record $329.3 billion in 2015.[8]There are strong calls for the EU to reduce the share of gas in its energy consumption by 2030 and not subsidize new gas pipelines and LNG projects, as doing so would contain the risk locking in dependence on fossil fuels, in contravention of the Paris Talks outcomes[9] and “rolling out the red carpet to Gazprom”.[10]According the European Court of Auditors, the European Commission “has persistently overestimated gas demand. The only way out is to focus renewables and energy efficiency to meet the EU’s s climate targets and reduce its dependence on foreign energy supplies”.[11]

Human rights organisations heavily criticise the EU’s stance towards the Southern Gas Corridor as its implementation would strengthen the dictatorship in Azerbaijan and thus worsens the human rights situation there. This in turn would create political instability in the country and in the broader region which could be used by Russia to push the EU out. Azerbaijan is alarmed by instability near its borders, be it in Iraq, Syria or Turkey. In addition, any internal political change in 2016 in Georgia due to the parliamentary elections will directly affect Azerbaijan. Unlike Azerbaijan and Russia, Iran openly acknowledges the needto improve its own human rights record and promised to pursue dialogue on this issue with EU "in a spirit of mutual respect and without preaching".[12]

New political reality and resistance to Russia’s interest in the region

Russia continues to fight for its influence in South Caucasus and tries to check Iranian power. It tries to increase its soft power in South Caucasus, especially in Georgia, through supporting political movements and civil society groups sympathetic to the Eurasian Union. As a part of this game, it tries to control the supply of Iranian gas to Armenia and even attempted to propose lower prices to Georgia in comparison to State Oil Company of the Azerbaijan Republic (SOCAR) in November 2015.[13] The signature of a memorandum on synchronizing electricity transmission systems between Russia, Georgia, Armenia and Iran in December 2015, serves Russia’s interest in establishing a single energy corridor stretching from the Black Sea to the Persian Gulf.

Russia, which traditionally supports Armenia over Nagornyy Karabakh issue, recently started sending signals to Baku that it may oversee a change in the conflict's status quo in favour of Azerbaijan as a way to keep Baku from swinging too close to the West or Turkey. As expected, Armenia has reacted negatively to this news.

Russia’s involvement in the civil war in Syria in support of the Bashar al-Assad regime had led to a harsh dispute between Turkey and Russia, increasing the security risks in a region. After Turkey downed a Russian Su-24[14]that had briefly intruded into its airspace in November 2015, Russia increased its military presence in Armenia and South Ossetia. Meanwhile, Ankara has begun to seek diversification of its natural gas supply away from Russia, which now provides for about 55 % of Turkish demand, against of 10 % from Azerbaijan.

It is clear that falling energy prices do not deescalate the situation in the South Caucasus. Therefore Georgia should be very cautious in approaching the prospect of a new energy deal with Russia. While Russia will not easily give up its military and energy plans in region, it has number of vulnerabilities that need to be exploited and Georgia needs to draw up plans for various scenarios. After joining of European Energy Community, Georgia should do its utmost - together with the EU, the other South Caucasus countries, Turkey and Iran - to find ways for sustainable energy policy development in the wider region. It should strengthen cooperation in order to reduce political risks through a human rights-based approach.

[1]There is a frozen conflict Armenia and Azerbaijan over the Nagornyy Karabakh region that began in 1988 and has been under fragile cease-fire since 1994. Turkey closed its border with Armenia in solidarity with Azerbaijan and has no diplomatic relations with Armenia. Armenia represents Moscow's only strategic partner in the region and hosts a large Russian military base in Gyumri. Azerbaijan has been supported by Turkey and has strong religious and linguistic ties to Iran. Georgia has tense relations with Russia, which has backed its separatist regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, recognising them as independent states. Georgia classifies Russia's support for these statemets and its military presence there as the "occupation" of 20 % of its territory.

[2]Lynch, D. (2006) Why Georgia matters, Paris: EU Institute for Security Studies, pp. 1-96.

[4] Project operator, BP said that it had already been unable to access part of the pipeline since the 2008 war.

[5]EU (2006) Decision No. 1364/2006/EG of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 September 2006 laying down guidelines for trans-European energy networks, Brussels.http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32006D1364

[6]The European Commission in June 2014 intervened to halt construction of Blue Stream pipeline from Russia to Bulgaria. In December 2014, Russia announced Turkish Stream, a project of similar dimensions that would bring gas across the Black Sea to Turkey for delivery to Europe at the Greek border.

[7] Russia also plays a negative role in EU-Armenia and EU-Ukraine relations. In 2013 Armenia was forced to reject signing an association agreement and instead to join the Russia-led Eurasian Union. For Ukraine the story ends when President Yanukovych fled to Russia due to the popular Euromaydan movement created after his refusal to sign agreement. This was followed by the annexation of Crimea by Russia and war between the Ukrainian government and Russian-backed separatists in Donbass.

[14]24 November 2015