This article explores the relationship between identity, heritage, and place in the villages of Akhali Khulgumo and Tambovka near Paravani Lake. It highlights the social change these villages have experienced since 1991. It examines how the interplay between memory of the past and the changing dwelling practices of the Dukhobor houses in Tambovka is constitutive of broader socio-cultural transformations, positioning the two villages also within current (geo)political dynamics and new identity negotiations.

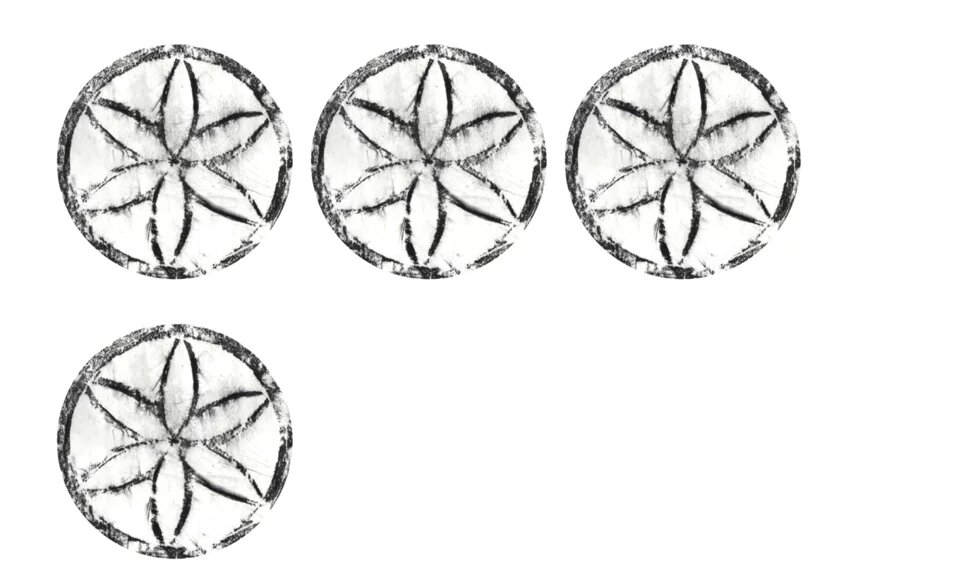

The article is based on a small collaborative research project that combined ethnographic and visual methods. Between August and November 2024, the authors conducted three weeks of ethnographic fieldwork in two villages in the Paravani area supported by Heinrich Böll Foundation. The work consisted of three eight-day field trips, each involving participant observation, using oral history method, one workshop, and visuals such as photographs, videos, and graphite stencil activities. Laura Mafizzoli wrote the article, analysing the material gathered with Giovannino Gabadze. Giovannino Gabadze, besides gathering ethnographic data, took the pictures and contributed to structuring and revising the article.

An Afternoon coffee: dwelling in the past and the future

On a sunny day in August 2024, the west bank of Paravani Lake sparkled under a clear, light blue sky. We had set out for a brief sightseeing trip to a Bronze Age settlement and its adjacent kurgan, located on the surrounding volcanic plateau at 2,100 meters above sea level1. As we walked down the hill, leaving the megalithic stones behind, we admired the stunning landscape. The plateau steppe seemed endless, and the lake’s colors mirrored the arid terrain. As we continued our walk toward the village of Tambovka, more stones emerged, revealing remnants of a cemetery belonging to the Dukhobor religious minority. Below the cemetery, along the shore, the first houses began to appear. The initial striking contrast that caught our curiosity was between two houses facing each other.

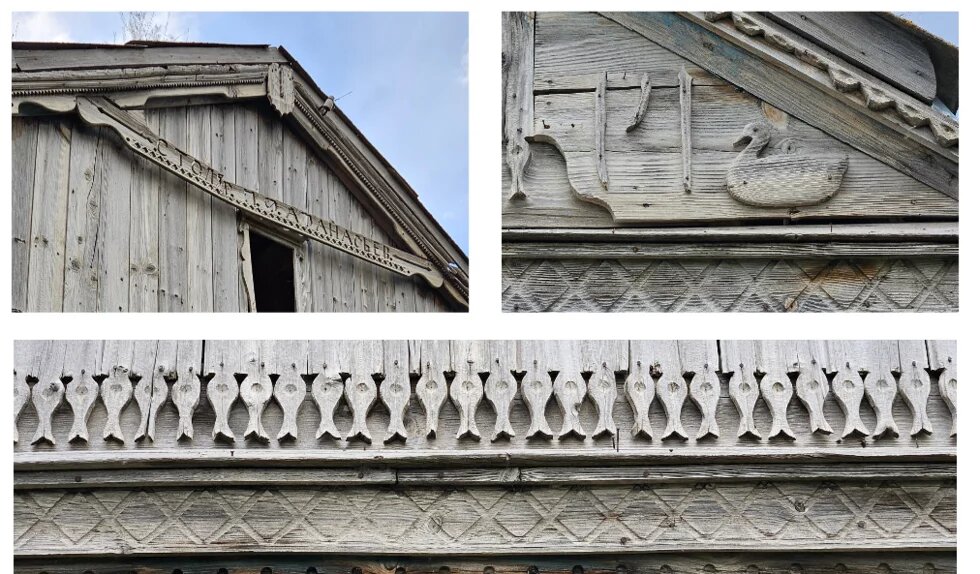

The first house was beautifully decorated in the typical Dukhobor style, featuring a sod roof and white and light blue patterns painted on the wooden façade. The second house, located directly across the road, had the same structure but one significant difference: instead of the traditional wooden façade adorned with white and blue ornaments, it was covered entirely in dark concrete. We later discovered that the first house belonged to Ms. Lena, the only Dukhobor left in the village, while the second house belonged to Ms. Mariya, a 60-year-old ethnic Armenian woman and a close friend of Ms. Lena’s2.

That afternoon, we knocked on Ms. Mariya’s wooden door. As her dog barked aggressively, warning of our presence, she came to the door and invited us into her small, one-story Dukhobor house, where she made us a pot of Turkish coffee. While the TV behind us played the news in Russian, Ms. Mariya shared part of her story. She grew up in Akhali Khulgumo, a village, as we shall see, located on the other side of the river, approximately 250 meters from her current house. After marrying the cousin of Ms. Lena’s second husband, she moved to Tambovka, the village on this side of the river. Her husband, an ethnic Armenian, had grown up in Tambovka. Ms. Mariya's house had been purchased by her husband’s ancestors after the Dukhobor owners, presumably related to Ms. Lena, passed away.

While Ms Mariya was explaining the intricate history of Akhali Khulgumo and Tambovka, a couple of her statements struck us as significant in understanding the sociocultural changes the villages were experiencing. In this context we understand such social change as the alteration of social norms and social relationships in everyday life that are intertwined with historical, demographic, economic, and political changes. Specifically, when we asked Ms. Mariya why she did not paint the house in the Dukhobor style, she mentioned that she did not like the ornaments and floral decorations and that she preferred a more “normal” look. Secondly, she consistently referred to Tambovka, the village's name, as something from the past, as if it no longer existed. She used the name Akhali Khulgumo for both villages, suggesting that the village “on the other side of the river” had absorbed Tambovka. She stated, “Now there are no more Dukhobors. Only Armenians live here”.

This statement was surprising to us for three main reasons. First, it suggests that Ms. Mariya views Ms. Lena as part of a culture that no longer exists. Second, it shows a specific relationship with the past, indicating that living in a house initially built by the Dukhobors does not necessarily mean reproducing the Dukhobors’ heritage of homemaking practices. Third, it illustrates a fracture between the past and the present, showing how a former two-village area had transformed into a place that was perceived as distinctly Armenian due to the absence of the Dukhobors, despite the material presence of the houses being an evident sign of Dukhobor's heritage.

Dominant understandings of heritage, such as those promoted by UNESCO, often portray it as something to be protected, surrounded by practices aimed at preservation, imagined as enduring unchanged over time3. This preservationist logic freezes heritage in the past, presenting it as evidence of cultural authenticity, “community,” and a claim to state and official recognition. In contrast, anthropological approaches consider heritage not as an object or set of monuments but as a dynamic, socially embedded system of practices: something lived, negotiated, and continually reconfigured in the present. As scholars have argued, heritage is deeply entangled in current sociocultural, political and economic conditions. It is both a site of contention and a tool for self-representation4. Once something is identified as “heritage,” it can become both empowering and exclusionary, used to assert belonging but also to create boundaries. In this sense, heritage is not simply a reflection of the past but a terrain for imagining futures, often amid marginalisation and uncertainty5.

Our analysis is guided by this anthropological perspective. We understand the heritage-making practices we observed in Akhali Khulgumo and Tambovka not as passive preservation but as forms of active negotiation of identities and place, through acts of care, reinterpretation, abandonment, or resistance. These practices carry both reflexive and political elements, opening space for residents to engage with, question, or redefine their relationships to place, history, and the Georgian state. What are the everyday narratives and practices that shape the place for its inhabitants? What does it mean to dwell in the present in the ruins of previous settlements and how does it influence the relation with the past and the future?

To answer these questions, in this article, we will analyse the social change reflected in Ms. Mariya’s statements to explore the practices of dwelling and heritage-making imbued in the transformation of Tambovka into Akhali Khulgumo. Due to limited resources and time constraints, we did not conduct archival research for this article. Instead, we rely on oral history and testimonies to reconstruct the historical and sociocultural dynamics of the two villages. Our findings are based on oral testimonies and participant observation we conducted during our stay in Tambovka and Akhali Khulgumo.

Tambovka and Akhali Khulgumo: layering history

The existence of numerous minority groups in Georgia, and more generally in the Caucasus region, is nothing new. Among these groups, Armenians currently make up the third largest ethnic population in Georgia, following the Georgians and Azerbaijanians. The Samtskhe-Javakheti region, due to its border with Armenia (and Turkey), has the highest density of the ethnic Armenian population, particularly in the municipalities of Akhalkalaki and Ninotsminda6. However, Samtskhe-Javakheti territory has been crossed and inhabited for millennia by different cultures. The area surrounding Paravani Lake in the Ninotsminda municipality crystallizes the layers of history that are characteristic of the Samtskhe-Javakheti region. As we mentioned at the beginning of this article, the area surrounding Tambovka and Akhali Khulgumo contains settlements that likely date back to the Middle Bronze Age (II millennium B.C.E), along with adjacent kurgans linked to the Trialeti and Martyopi cultures7. While conducting a small archaeological excavation in one of the villagers’ gardens, archaeologists Darejanashvili and Pataridze found that the majority of Tambovka’s area was built above the ruins of a Georgian Medieval village (X-XII century) typical of the Javakheti region8. The area was almost left uninhabited for centuries, except for being used to access other locations in Georgia. Only in the 1840s was the area repopulated, and the area surrounding Paravani Lake became the “land of the Dukhobors”9.

The Dukhobor community, originally based in the Russian Empire, underwent a significant transformation in the 1840s as a result of imperial religious policy. When Nicholas I succeeded Alexander I, the state adopted a harsher stance toward non-Orthodox religious groups, labeling them as “sects”. In 1839, the tsar issued a decree mandating the deportation of the Dukhobors from the Melitopol district to the Transcaucasus10. The deportation aligned with a broader policy of relocating sectarian groups to the empire’s newly conquered southern territories, distancing them from the Orthodox population and facilitating control over peripheral regions. Although the resettlement was ordered in 1839, implementation was delayed due to logistical issues, including a lack of available land. The decree stipulated that only Dukhobors who refused to convert to Orthodoxy would be deported; those who accepted conversion could remain11. According to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, 217 Dukhobors converted officially12.

The forced migration unfolded in three waves beginning in 1841, with the Akhalkalaki district in the Georgian-Imereti province (present-day Georgia) designated as a primary destination. The first convoy of 795 people arrived in Tbilisi in September 1841, though only 773 completed the journey. The broader relocation process extended until 184513. Communities were founded in the regions of Javakheti and Dmanisi in Georgia as well as in Kedabek in present-day Azerbaijan and Kars in present-day Turkey. In the Ninotsminda district, there were eight Dukhobor villages: Bogdanovka (known today as Ninotsminda), Gorelovka, Tambovka, Orlovka, Spasovka, Troskoye (or Kalinino, currently Sameba), Yefremovka, and Rodionovka (currently Paravani). Four hundred ninety-five families, amounting to 4,097 Dukhobors, settled in the Javakheti region, while around a thousand individuals moved to the present-day Dmanisi district14. According to archaeologists, the Dukhobors who relocated and founded the village of Tambovka used materials from the remains of Georgian medieval settlements to create the architecture to form the typical Dukhobor one-story houses15. Such use of the remnants of materials from previous settlements suggests a “continuity in the discontinuity” of the social order, thus showing how the meanings of these material forms undergo material shifts that enable different forms of social life16.

The area surrounding Tambovka experienced another wave of resettlement a few decades after the Dukohbors settled. The remnants of materials from the past again became an important aspect of creating new socialities. When Javakheti became part of the Russian Empire after the 1828-1829 Russo-Turkish War, approximately 58,000 Armenians migrated from Ottoman territories to the region. Another wave of migration then followed the First World War and the Armenian Genocide in 191517. Some of these Armenians settled in the village of Khulgumo, near Akhalkalaki. According to historical sources and our informants, some Armenian families from Khulgumo moved to Tambovka around 1924 and built the first houses on the left side of the river, naming the village “Akhali Khulgumo” (New Khulgumo)18. Some of these houses were inspired by the Dukhobor style and used materials from the surrounding area, including large stones likely taken from medieval settlements. Over time, more Armenian families arrived from Akhalkalaki, and many local men married women from surrounding villages such as Aspara, Rodionovka, Akhalkalaki, and Bogdanovka, increasing the number of Armenian families in the area. According to our interlocutors, Dukhobors in Tambovka and Armenians in Akhali Khulgumo found a way to coexist despite initial disagreements. Probably also because of the construction of the common school and the House of Culture during the Soviet period on the empty land between the two villages, the two villages developed a new form of sociality. Some marriages between the two communities also took place, including Ms. Lena marrying Ms. Mariya’s cousin. After the fall of the Soviet Union, the number of Dukhobor families in the region declined as many moved to other cities or emigrated from the country19. As the villages experienced this demographic shift, many Armenians purchased the abandoned Dukhobor houses. In 1990, three hundred Dukhobors lived in Tambovka, but by 2006, only nine remained20. When we conducted our field trip in 2024, only one person, Ms. Lena, remained from the Dukhobor community, while 35 Armenian families lived in Akhali Khulgumo and Tambovka. At the time of our research, many of these families in Tambovka lived in houses originally built by Dukhobors, such as the one Ms. Mariya mentioned at the beginning of this article. As we can see, the area of these two villages has, over the centuries, been inhabited by different groups, and the material traces of earlier settlements have been adapted to meet the present-day needs of new settlers. Here, heritage emerges not as a set of practices and objects to be preserved untouched, but as a continuous renegotiation of space and place among groups shaped by experiences of displacement and various forms of marginality.

The fading border between Akhali Khulgumo and Tambovka

When we arrived in September 2024, all the inhabitants, from different generations, in Tambovka and Akhali Khulgumo, showed us with pride the pictures and the videos of the Centenary of Akhali Khulgumo (100 years since its foundation in 1924) they celebrated on the 6th of July 2024. Almost 400 people participated. It was such a big event that even relatives living in Russia came for the celebration. It was a self-organized event, each family contributed to the organisation with 500 GEL, and the only person who did not participate in the celebration was Ms. Lena, the only Dukhobor left in the village. This celebration was, to us, but also to the villagers, perceived as a turning point to state the new identity of the village(s) as Akhali Khulgumo. This celebration was also the culmination of the demographic changes that occurred since 1991 which led to a new composition of the villages. This new composition meant for the ethnic Armenian residents to live in one village, that is Akhali Khulgumo, and Tambovka was already becoming part of the past. According to our interlocutors, Ms. Lena and her colourful Dukhobor house were the only living remnants of Tambovka. This perception of Tambovka as past history was evident in the vague ways our interlocutors defined the border between Tambovka and Akhali Khulgumo.

Some inhabitants identified the river Shashka (or “Chachka”) as a physical border, linking it to the temporal moment when Armenian settlers founded Akhali Khulgumo on the river’s west bank in 1924. Others, however, pointed to the Russian school, opened in the 1980s, and the adjacent House of Culture as marking the spatial division. Still, we had the impression that these responses were less about deeply held beliefs and more about offering an answer to outsiders.

For instance, Ms. Mariya’s would interchangeably use “Tambovka” and “Akhali Khulgumo” as if they were the same village. She would use “Tambovka” when talking about the past, when Dukhobors were the primary inhabitants, and she would call Tambovka “Akhali Khulgumo” when talking about present issues. Many inhabitants of Tambovka and Akhali Khulgumo shared Ms. Mariya’s view. Whenever inhabitants talked about Tambovka and Akhali Khulgumo, they spoke about the history of Tambovka and they knew about its past, yet it was a past that did not belong to their new history because Akhali Khulgumo celebrating 100 years became a marking point to state that Akhali Khulgumo could begin a new chapter of history. Moreover, the elderly still had their identity cards listing Tambovka as their birthplace instead of Akhali Khulgumo, remarking “the government is slow to recognise the changes occurring in this part of the country”. Yet, the young generations already had Akhali Khulgumo in their birth certificates and on their identity cards, showing state recognition of the new identity of Tambovka as Akhali Khulgumo.

From Dukhobor to Armenian dwelling practices

At the time of our fieldwork, many houses built by the Dukhobors had fallen into disrepair, with damaged roofs and crumbling walls. Some were abandoned, while others were inhabited by Armenians. Aside from Ms. Mariya’s house, which featured an altered façade, most of these houses showed clear signs of decay. Visually, they could be seen as a spatial border between Akhali Khulgumo and Tambovka, as some of our interlocutors suggested. Yet their deteriorated state also reflected deeper social and economic shifts, such as unemployment, poverty, but also migration, as we shall see in the next sections.

The state of decay of the Dukhobor houses was particularly distressing for Ms. Lena, the only remaining Dukhobor in the village. Ms. Lena became our window into a disappearing world. A very active woman in her 70s, she was often seen painting her house, hosting guests from nearby villages, or chatting with tourists who admired her blue home. When we visited in September 2024, she had just finished repainting it; the bright blue paint looked fresh and vibrant. She spoke of the challenges faced by the Dukhobors who settled around Lake Paravani in the 19th century, rebuilding their lives after resettlement and adapting to the harsh climate. Since the area lacks trees, wood was imported from the Bakuriani region. Flat stone slabs and clay were used for roofs, later topped with grass, which served as insulation against cold and moisture. These houses needed annual maintenance to withstand the harsh Javakhetian winters, with temperatures dropping to -20°C. Ms. Lena explained that checking the roof before the first snow, usually in November, was essential to prevent collapse under heavy snow. She proudly recalled how Dukhobor families worked together from mid-September to early November to prepare for winter.

One such communal practice was whitewashing the outer walls of the houses. Ms. Lena nostalgically recalled how Dukhobor families in Tambovka would gather and paint their homes, giving them an “ethereal appearance.” She remembered sharing a house with her mother-in-law and another bride, each responsible for painting a section within three days. The striking white houses stood out against the dark landscape surrounding Lake Paravani and were affectionately nicknamed “white swans.” Women would sometimes use blue dye to create ornamental patterns. Once all the houses were painted, the village held a celebration, Kazanskaya, on November 7th, marking the end of this important collective effort. For Ms. Lena, this work was not just about maintenance; it reinforced a sense of community and reproduced the village’s social structure

When speaking about this lost community, Ms. Lena expressed sadness and frustration at what she saw as a lack of care shown by the Armenian families now living in the Dukhobor houses. She emphasized that the biodegradable materials required regular maintenance to prevent decay. For her, this caretaking was not just practical, nor merely a cultural marker, but something deeply tied to the Dukhobor past. It was rooted in the hardships her ancestors faced when they had to resettle and build their homes from scratch. The fragility of the materials used to construct the house, along with the yearly maintenance, revealed a delicate balance that reflected the experiences of the Dukhobor settlers who had to adapt to a new environment and make use of the limited surrounding materials they had to withstand the harsh climate around Paravani Lake. For Ms. Lena, continuing the home maintenance and the practice of whitewashing was not only an act of proud resistance to a future in which her ancestors’ homes were decaying, but also a way to preserve the memory of their struggles.

For Armenian residents, however, the houses did not represent such struggles. The houses represented functionality, a source of shelter and warmth. Many expressed the need to “modernize” them. Dukhobor-style houses often featured new, Euro-style plastic windows in place of the original wooden frames. When asked why she does not whitewash or decorate her house in the “Dukhobor style,” Ms. Mariya responded:

“They [the Dukhobors] have different tastes; mine is different. I do not like my house painted. Who will take care of it? Who will paint it? I do not have time for this. I do not like it, and it is hard to do. To continuously do it, you must love doing it. I changed my house in this way for that reason.”

Her statement illustrates that for Ms. Mariya, the house was a structure to adapt for comfort and efficiency. Similarly, many Armenian residents altered their houses while keeping their basic structure. Sod roofs were replaced with modern materials that required less upkeep. Others installed new doors to improve security, important for families who left the village in winter to live in cities like Ninotsminda and Akhalkalaki. This seasonal migration became common in the last decade, especially among elderly residents seeking more comfortable living conditions.

These changes demonstrate how contemporary needs—economic, climatic, and social—shaped the ways in which Dukhobor houses are reused. For Armenian residents, modern materials represented progress, enabling new ways of living. Just as the social and demographic boundaries between Tambovka and Akhali Khulgumo were shifting, so too was the built environment. The decaying Dukhobor houses stood as reminders of a distant and largely unknown past, while their repurposing marked a new chapter in the village’s history. This transformation embodied new memories and forms of sociality, shaping how the Armenian community related to the past and imagined the future of Akhali Khulgumo, with modern houses and better life conditions.

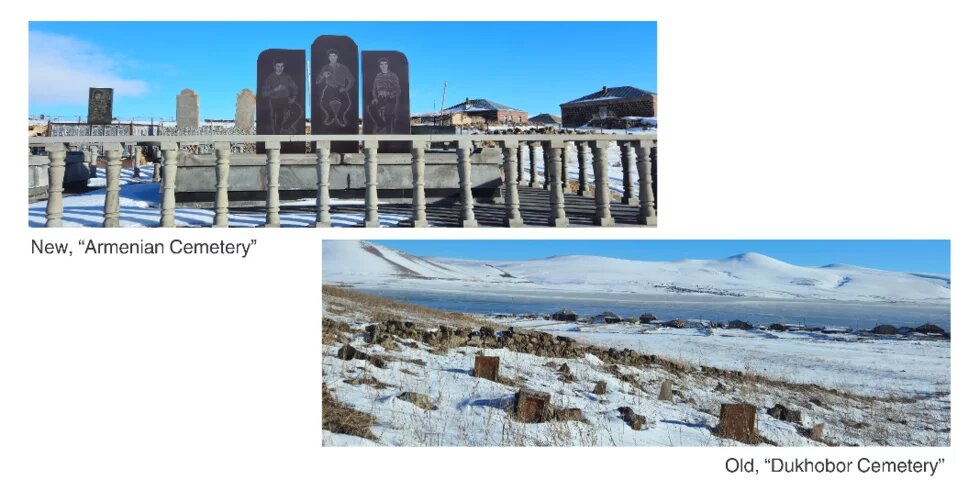

Armenian and Dukhobor Cemeteries

Just as the shifting village identity was reflected in the neglected state of many Dukhobor houses, it was also visible in the condition of the cemeteries. The newer cemetery, located near Akhali Khulgumo, served the Armenian community, while the older cemetery, situated about 150 meters uphill at the edge of Tambovka, had been the Dukhobor burial ground. Their peripheral locations echoed the historical separation between the two groups. However, by the time of our fieldwork, the demographic change of the village and the near absence of Dukhobors in Tambovka had become starkly visible in the contrasting conditions of the two cemeteries. The Armenian cemetery was well-maintained, enclosed by a protective fence, and adorned with modern gravestones featuring laser-engraved portraits and colorful artificial flowers. Bowls of water were placed near candles to prevent fires, reflecting ongoing care and attention. In contrast, the Dukhobor cemetery was overgrown and neglected. Wildflowers, nettles, and weeds had taken over, and cattle and wild animals roamed freely. Village children occasionally used it as a playground or picnic spot.

This transformation of a sacred space into a “recreational” one is not, however, merely a matter of neglect, as Ms. Lena told us. It reveals a deeper insight into how heritage is closely tied to the present and is a lived experience. Namely, the Dukhobor cemetery is used as a space for the Armenian children to play, or occasionally as a picnic spot, and also as a space to take the cattle to pasture. In this way, it becomes embedded in everyday practices that fall outside the domain of death, illustrating how the Armenian community coexists with the remnants of the Dukhobor community through their daily activities. Consequently, the Dukhobor cemetery does not function as a site of ancestral significance for the Armenians and therefore does not occupy the same moral or symbolic horizon. It has been assimilated into the routines of daily life, recast through practices that engage with the material remains of the past, transforming a site once regarded as sacred by the Dukhobors into one redefined through new purposes and meanings by the Armenian community.

Navigating place: between isolation and inclusion

As Tambovka was becoming Akhali Khulgumo socially, culturally, and ethnically, new negotiations of place and identity emerged while we were on fieldwork. For instance, one evening, as we ate cake with our neighbor Ms. Anastasiya, a 45-year-old woman, and her 16-year-old daughter, Tatyana, Ms. Anastasiya lamented not knowing the Georgian language. She is ethnically Armenian and speaks Armenian, Turkish, and Russian21. She studied Armenian at school and recalled struggling to learn Russian as a child, eventually picking it up through everyday conversation with the Dukhobors from Tambovka. When asked why she now wanted to learn Georgian, she explained: “I have health issues and frequently visit Tbilisi, where I struggle to communicate with doctors about my condition.” To navigate this linguistic barrier, she relied on a relative who had recently graduated from a university in Tbilisi. When asked whether he spoke Georgian well, she laughed and said, “He is like a Georgian,” noting that he had attended a Georgian kindergarten and school. Tatyana joined in, playfully adding, “We are Georgians, too!”

Despite numerous integration efforts by both the Georgian state and international organizations, our interlocutors conveyed a deep sense of isolation and feeling of being left behind by the state. This sense of marginalization and isolation was reinforced by poor infrastructure, scarce employment opportunities, and, most critically, the alienation caused by not speaking Georgian language. Currently, Georgian is taught for only two hours per week at local schools, with even fewer learning opportunities for adults22.

Ms. Anastasiya was not alone in expressing frustration and a desire to learn the Georgian language. For many people of her age, Georgian language is a practical necessity for accessing medical care, handling bureaucratic procedures, and engaging with the state agencies. Among the younger generation, however, this sense of belonging appeared more assertive. Tatyana’s remark, “We are Georgians, too,” marked a shift in how their identity of being Armenians with a Georgian passport was being negotiated and perceived. Many young people in the village expressed aspirations to attend university in Tbilisi. Tatyana, in her final year of school, was worried about her proficiency in Georgian and the upcoming national exam. Another girl, Kristine, aged 15, spoke Georgian more fluently, thanks to frequent visits to her grandmother in Guria. She emphasized the importance of speaking both Armenian and Georgian, unlike her parents, who mainly spoke Armenian, Turkish and Russian, because she identified as both. She felt that the Turkish and Russian languages no longer reflected her current identity.

Another aspect underpinning further exclusion at the time of our fieldwork was the uneven literacy levels among different generations in the villages, as well as the challenges related to the oral and written transmission of languages. Younger generations, having attended school, could read and speak Russian and, to some extent, basic Georgian. Most children spoke Armenian (and also Turkish) at home but were unable to read Armenian or Turkish. This gap was even more pronounced among older generations, including their parents, who, unless they had studied at a university in Tbilisi or Yerevan, could read only Russian, but neither Georgian, Turkish or Armenian. As a result, Russian was the only language that the majority of older generations who had not worked outside the villages could both read and speak.

Language exclusion, however, is only one of the many challenges that the villagers face. The harsh climate of Paravani Lake further contributes to their isolation. Situated at an altitude of 2,100 meters on the Javakheti volcanic plateau, the villages are exposed to severe winds and snowstorms, resulting in almost complete isolation during the winter. Many villagers have complained about the lack of state investment regarding infrastructure23. The road connecting the villages of Tambovka and Akhali Khulgumo to the main road is just four kilometers long but in winter is often covered by snow, making it impossible to leave their homes, let alone the villages. Many villagers, for instance, move to the cities of Akhalkalaki and Ninotsminda in winter and return to Akhali Khulgumo and Tambovka in spring. The villagers primarily rely on fishing, cheese making, and cattle farming for their livelihoods. However, the land they have is insufficient to provide a stable income. Due to the high altitude and harsh climate conditions very few agricultural products can be grown, making it challenging for them to achieve self-sufficiency.

Unemployment has been another driver of migration. Some villagers moved to Armenia or Russia in different periods, first in the 1990s and then after the closure of the military base (see below). Yet, some of the villagers we spoke to in 2024 were considering joining their relatives in Russia, where they spoke the same language, making integration and job seeking easier. These long-standing transnational ties to Armenia and Russia, as well as feelings of isolation and dispossession by the state, were shaped by the region’s complex history. In fact, while the new Armenian settlers arrived in 1924 and founded Akhali Khulgumo and started coexisting with the Dukhobors community, the Javakheti region remained isolated from Tbilisi’s central authorities during Soviet times due to its location along the border with NATO-member Turkey. Meanwhile, the open border with Soviet Armenia made it more accessible for the local population to travel there rather than to other parts of Georgia. The region was designated as a restricted border zone, imposing strict travel limitations on outsiders. After the fall of the Soviet Union this area remained restricted due to the presence of the Russian 62nd military base in Akhalkalaki, which limited access to Javakheti for non-residents and those not employed by the base until 2007. The Russian regional military base, first established in the early nineteenth century, housed around 3,000 soldiers, with an estimated half of them from the Javakheti region. Its long-term presence left a “Russianizing” imprint, which continued to shape both political sentiments and linguistic preferences in the region long after its closure24. During our fieldwork, several interlocutors expressed pro-Russian views, but these were deeply intertwined with economic uncertainties, geopolitical anxieties, and the perceived failure of the Georgian state to provide viable alternatives.

These pro-Russian leanings are rooted in the legacies of Tsarist and Soviet rule and are reinforced today by the dominance of Russian media in the region. While some see the EU as a potential protector of minority rights, many ethnic Armenians told us that they hesitated to support EU integration if it threatens their ties with Russia, where they can move for seasonal work and whose language is also familiar. Several Civil Society Organizations like CENN25, UNAG, Civic Integration Foundation 26, ECMI, and SEAG in the past have held meetings in Samtskhe-Javakheti to promote European integration and inform people about the EU-Georgia Association Agreement27. However, ethnic Armenians are generally more cautious about NATO membership, fearing Turkey’s increased military presence in the region. For instance, they did not support closing the Russian military base in Akhalkalaki, viewing it as essential for protection against Turkey and Azerbaijan28. These pro-Russian attitudes must be understood not simply as geopolitical preferences but as part of a broader experience of marginalization of the region that was still ongoing at the time of our fieldwork.

One evening, we were at Ms. Serafima’s house. We befriended her and spent many evenings drinking coffee and gossiping. She kindly hosted us for a week in her home. One evening, she seemed anxious and told us that the house needed major renovations. She pointed at the room where we were sleeping, with its moldy, humid walls. Sighing, she said, “I do not know if and when we will do the renovation. If we move to Russia, we won’t; we’ll leave the house. If we decide not to move, we will start doing the renovation in spring”. Ms Serafima did not want to move to Russia. Indeed, she repeatedly expressed her desire to learn the Georgian language. However, it was not her decision to make. If her husband and son decided to move, she had to follow them. The decision depended on many circumstances; however, it seemed to hinge on the Georgian parliamentary elections on October 26. We were, in fact, in the villages until October 25, and questions about what to do and who to vote for saturated everyday conversations.

There is a general assumption that ethnic minorities, particularly Armenians and Azerbaijanis, unconditionally vote for the ruling party, reproducing a Soviet legacy that is almost essentialist29. Although this might hold some truth, as the October 2024 election results indicated, it is important to contextualize and unpack some of the issues at stake to understand these results30. When we were in Akhali Khulgumo and Tambovka, many of our interlocutors expressed disappointment with the Georgian Dream party, saying that Georgian authorities had completely forgotten them. As previously discussed, this sense of abandonment manifested through inadequate infrastructure, a failing education system, and limited employment opportunities. Many told us that voting for Georgian Dream or any other party was “all the same,” since, in their view, little had changed over the past decades, whether under Saakashvili or afterward. Yet this political indifference coexisted with a desire for participation. Every family we spoke with expressed their intention to vote. This dual feeling, of exclusion and hope, was bittersweet. On the one hand, people felt neglected and saw their participation as meaningless. On the other hand, they were excited to partake in the electoral process, which they perceived as a form of inclusion in Georgia’s political life.

Two days before the elections, Mr. Ivanya hosted relatives to discuss the vote over coffee and invited Giovannino, one of this article’s authors, to join and explain the political landscape. Giovannino described the parties, coalitions, and leading figures, sharing charts and posters prepared by online media platforms. However, it soon became clear that Mr. Ivanya and his guests were only familiar with Georgian Dream, UNM, and the Coalition for Changes, and it proved difficult to convey the nuances among the various political alternatives.

“I have to light the fire!”: reproducing isolation

One evening, we were with Ms. Serafima and her husband, Mr. Ivanya, and Mr. Ivanya handed us a newspaper featuring the Georgian Dream’s colours, with a bonus calendar enclosed. The newspaper and the calendar were entirely in Armenian language, with many images showcasing Georgia’s development and achievements under the Georgian Dream’s mandate. Notably, there were no pictures of Paravani or the municipalities of Ninotsminda and Akhalkali. Yet, Ms Serafima and Mr Ivanya, like many other Armenians in the villages, could not read the Armenian language. We spent a few moments watching Mr. Ivanya flip through the pages, interpreting the images that depicted a glorious journey of Georgian economic development and promises for an even brighter future. When asked why the Georgian Dream gave them a newspaper in the Armenian language and not in Russian, Ms Serafima told us, “I don’t know, probably because we are Armenians”. If this response hinted at an attempt by the Georgian Dream to include the Armenian community within the political landscape, what followed was even more contradictory. Ms. Serafima and her husband collected many of these newspapers and calendars, which led us to believe they were major supporters of the Georgian Dream. When we asked why they had so many newspapers, Ms. Serafima replied, “I have to light the fire!”. This small episode demonstrates that, despite the state's attempts at inclusion, not being able to read Armenian led them to treat the newspapers as valuable material for lighting fires, rather than for reading.

The apparent strategic approach by the Georgian Dream to secure the loyalty of villagers through an attempt at inclusion through the newspaper in Armenian language, while simultaneously not knowing that many inhabitants could not read Armenian language, perpetuated instead their destitution and isolation, leveraging the impoverishment of the area31.

Heritage as a lived experience: final remarks

This article explored the social and cultural transformation of the village of Tambovka into Akhali Khulgumo in the highland rural area near Paravani Lake. Once inhabited primarily by Dukhobors, a spiritual ethnoreligious group of Russian origin deported to the Caucasus in the 19th century, the area is now home to ethnic Armenians whose dwelling practices and attachments to place reflect broader shifts in identity and belonging. Drawing on ethnographic and visual research, we explored how the disappearance of the Dukhobor community and the increasing presence of ethnic Armenians have reshaped both the physical and symbolic landscape. Through practices of dwelling and everyday interaction with the material remains of the past, such as Dukhobor houses and cemeteries, we showed how heritage becomes a dynamic and sometimes contested terrain, negotiated through acts of care, neglect, and adaptation.

In tracing the transformation of Tambovka into Akhali Khulgumo, we argued that heritage-making reflects both continuity and rupture, empowerment and exclusion. It provides tools for the Armenian community in Akhali Khulgumo to assert presence and belonging, even as it reinforces boundaries of who belongs and whose past matters. Ultimately, heritage in this context is not simply about the preservation of memory, but about the lived negotiations of identity in the midst of demographic, political, and economic change. By examining the daily discourses and practices of the village’s residents, particularly the Armenian community, we have shown that heritage is not a fixed, immutable entity but a dynamic, socially embedded process. In the case of Tambovka’s transformation into Akhali Khulgumo, heritage-making is intertwined with political, social, and economic realities, reflecting both continuity and discontinuity with the past, and shaping the inhabitants' relationship with their past and their future. Our findings highlight how marginal regions like Javakheti are not merely peripheral but constitute critical sites for understanding national belonging, political participation, and the lived experience of heritage. As the younger generation increasingly identified with the Georgian state, despite marginalisation and isolation, the two villages emerged as spaces of negotiation where new forms of dwelling, identity, and memory continue to unfold.

The rewriting and revising of this article by Laura Mafizzoli, as well as its publication, have also received additional support for the long-term conceptual development of the research organization RVO: 68378076, Institute of Ethnology of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic.

The Content of the article is the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Heinrich Boell Foundation Tbilisi Office - South Caucasus Region

Footnotes

- 1Kurgans are circular burial mounds typical of the Neolithic period and Bronze Age.

- 2All the names of our interlocutors have been changed to keep anonymity.

- 3Macdonald, S. 2018. ‘Heritage’, in H. Callan (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Anthropology, Wiley-Blackwell. p.3

- 4Salemink, O. 2021.” Anthropologies of Cultural Heritage”. In L. Pedersen, & L. Cligget (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of cultural anthropology. Pp. 409-427.

- 5

Kockel, U. et al, 2007. Cultural Heritages as Reflexive Traditions. Palgrave Macmillan.

- 6Moratelli, Francesco. "The Armenian Minority of Post-Soviet Georgia and Its Identity." Thesis, Ca' Foscari University of Venice, 2018/2019. http://dspace.unive.it/bitstream/handle/10579/16819/870244-1235140.pdf?…

- 7For more information about kurgans in Georgia, see: Narimanishvili, G.; Shanshashvili, N & Narimanishvili, D. 2022. The Megalithic Monuments of Georgia. Tbilisi.; Hopper, Kvavadze, Rova, E. (2023) ‘Kurgans, Churches and Karvasla: Preliminary results from the first two seasons of the Lagodekhi Archaeological Survey, Georgia’ in 12ICAANE. Proceedings of the 12th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East 06-09 April 2021, Bologna

- 8This type of settlement is called darani, and it consists of underground shelters linked by each other through tunnels. See: Robinson, Abby; Khaburdzania, Giorgi. 2018. Medieval Underground Shelters (Darnebi) of South-west Georgia in Landscape Archaeology in Southern Caucasia, pp. 119-130, 2018/05/08

- 9https://www.rferl.org/a/georgia-dukhobors-orthodox-sect-pacifist/321612…

- 10See Masimov, A. 2022. “History of the Dukhobor Religious Sect and Its Transformation in Transcaucasia in the Late 19th Century”. Bakuresearchinstitute.org

- 11For more information about the persecution and the deportations, see Tchertkoff, V. 1897. Christian Martyrdom in Russia: Persecution of the Spirit-Wrestlers (or Dukhobortsi) in the Caucasus, London: The Brotherhood Publishing Co. https://iverieli.nplg.gov.ge/bitstream/1234/522860/1/Christian_Martyrdo…

- 12Masimov, A. p.4.

- 13 Masimov, A. p.5.

- 14

Lohm, H, Dukhobors in Georgia: A Study of the Issue of Land Ownership and Inter-Ethnic Relations in Ninotsminda rayon (Samtskhe-Javakheti), ECMI Working Paper #35, 2006.

- 15Beridze, M., Ghutidze, I., Kavrelishvili, R., Gaprindashvili, K., Balasaniani, M., Beridze, M., Metreveli, K., & Khazalashvili, N. (2023). Research and documentation of onomastic material of Javakheti: Ninotsminda Municipality. Tbilisi: Publishing House "Natlismtsemeli", p. 156

- 16Hodder, I. 1994. ‘Architecture and Meaning: The Example of Neolithic Houses and Tombs in Architecture and Order: Approaches to Social Space, edited by Michael Parker Pearson and Colin Richards. London: Routledge, p.77-78.

- 17Blauvelt, K., Berglund, C. "Armenians in the making of Modern Georgia", K. Siekierski, S. Troebst (ed. by), in Armenians in Post-Socialist Europe, Köln, Böhlaup, 2006, p. 71.

- 18Beridze, M., Ghutidze, I., Kavrelishvili, R., Gaprindashvili, K., Balasaniani, M., Beridze, M., Metreveli, K., & Khazalashvili, N. (2023). Research and documentation of onomastic material of Javakheti: Ninotsminda Municipality. Tbilisi: Publishing House "Natlismtsemeli" p. 157-162

- 19By the time of our fieldwork in 2024, the village of Gorelovka had the most active Dukhobor community and was the main one among the eight villages where Dukhobors still live. See: Beard, N. and Grigalashvili, N. “Georgia's Dukhobors: An Orthodox Sect That Believes In Pacifism, Gender Equality? “ 2022. https://www.rferl.org/a/georgia-dukhobors-orthodox-sect-pacifist/321612…

- 20

Lohm, H., p.14, Dukhobors in Georgia: A Study of the Issue of Land Ownership and Inter-Ethnic Relations in Ninotsminda rayon (Samtskhe-Javakheti), ECMI Working Paper #35, 2006 p.14

- 21As the majority of Armenian families living in Akhali Khulgumo are descendants of Armenians who fled the Ottoman Empire to escape the genocide, Turkish was a language spoken by their ancestors and transmitted orally across generations. Many Armenians in Akhali Khulgumo still speak Turkish, as they conduct business with Azerbaijani shepherds, to whom they entrust their flocks during the spring, summer, and autumn for pasturing and transhumance.

- 22Several initiatives have aimed to reform the education system and promote the study of the Georgian language (see, for instance: https://cciir.ge/en/projects-eng/integration-of-society-through-multili…) and, more in general, to face strategically some of the challenges that ethnic minorities in Georgia face on a daily basis. See: Salakhunova, A. 2025. “Georgia's Path to Inclusivity: Integrating Ethnic Minorities through Education and Policy Reform”. Eurac research. https://www.eurac.edu/en/blogs/eureka/georgia-s-path-to-inclusivity-int…. Despite the many projects funded by the Georgian government and supported by U.S. and European organisations, research consistently shows that minorities remain largely alienated from Georgian social, economic, and political spheres. See: Gabunia, K.; Amirejibi, R. 2021. “Georgia’s Minorities: Breaking Down Barriers to Integration”. Carnegie Europe; Berglund, C., Dragojevic, M., & Blauvelt, T. (2021). Sticking Together? Georgia’s “Beached” Armenians Between Mobilization and Acculturation. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 27(2), 109–127.

- 23See also: Khmaladze, M. 2024. “The disappearing villages of Samtskhe-Javakheti” OC Media https://oc-media.org/the-disappearing-villages-of-samtskhe-javakheti/

- 24Berglund, C., Dragojevic, M., & Blauvelt, T. 2021. p. 113.

- 25https://www.cenn.org/bridging-communities-and-democracy-civil-societys-…

- 26https://csogeorgia.org/en/post/ertad-mushaoba-integratsiis-sauketeso-sa…

- 27See also: https://en.heks.ch/sites/default/files/documents/2023-03/Ongoing_0.pdf

- 28See also Øverland, I. “The Closure of the Russian Military Base at Akhalkalaki: Challenges for the Local Energy Elite, the Informal Economy and Stability”, The Journal of Power Institutions in Post-Soviet Societies [Online], Issue 10 | 2009, Online since 07 December 2009, connection on 30 April 2025. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/pipss/3717; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/pipss.3717

- 29See: https://socialjustice.org.ge/en/products/archevnebi-da-etnikuri-umtsire…

- 30https://civil.ge/archives/631386

- 31See also: https://www.e-flux.com/notes/646356/in-the-name-of-peace-georgia-s-post…