The theme of Armenian Genocide is currently taught in Armenian schools in eighth grade history classes.[1] The National Standard document for Armenian History instructs that the theme of Armenian Genocide, referred to as “Medz Yeghern,” should be taught as a subchapter within the chapter “The Armenian People during the years of World War I.” The subchapter should contain knowledge on the following: the term “Genocide”; The Young Turks’ planning and implementation of the Genocide of the Armenians; the effects of Medz Yeghern and the lessons learnt; and self-defense (resistance) battles fought in 1915, and their significance (2012, 9). In a similar vein, the World History textbook presents information on the Armenian Genocide as an auxiliary text to the main themes surrounding World War I (Stepanyan et al. 2013, 209; 218-219). However, historical education is conducted not only through lessons on national and world history, but also through national language (literature) subjects, as well as subjects related to nature, music, art, etc. Particularly, the National Standard for the subject Armenian Language and Literature contains several literary works directly concerning episodes of the Armenian Genocide (2011). These textbooks refer to the Genocide and its context also within the biographies of many writers of the modern era, some of whom were killed in the Genocide (ex., 8th grade).

Historical education, in fact, starts much earlier than the teaching of special subjects: it starts from the very beginning of school education through the ABC, Native Language, Me and the Surrounding World and Music and Art subjects. This article focuses on the educational content and practices regarding the memory of the Armenian Genocide which appear before (in terms of students’ age) the subjects of national and world history enter the curriculum. It is based on field data gathered by the author in Yerevan from 2011 to 2013 as well as the review of textbooks officially used in Armenian schools for the academic years 2011-2013.

The review of the textbooks found that, up until the fourth grade, official curriculum made no mention of the terms “Armenian Genocide,” “Medz Yeghern” or any other direct mentioning of the events of 1915, neither within chapter and lesson titles, nor within the themes and plots of stories and poems. One prompt “reminder,” however, was mentioned in the fourth grade textbook Me and the Surrounding World within a passage referencing Armenian writer Hovhannes Tumanyan. Having mentioned his merits as a writer, the text also says: “Tumanyan has been with his people during the hardest times. He was spending his whole time with the Armenian refugees, survivors of the 1915 Medz Yeghern” (Hovsepyan et al 2010, 98). Another small “iconographic memory spot” within the textbooks is met by students in the second grade language textbook (Mayreni) in the form of a picture of the monument dedicated to the victims of the Armenian Genocide. This image is placed within a collage of pictures consisting of symbols of the Yerevan, which itself is illustrated by a text entitled “Yerevan” (Sargsyan et al 2010). Thus, in a general sense, official educational content used in elementary education does not refer to the memory of the Armenian Genocide. It is only starting from the fifth grade (which is officially the first year of basic level of general education in Armenia)[2] that textbooks mention the Armenian Genocide, as demonstrated by the subject Hayrenagitutyun. Both versions of the subject textbooks refer to the theme, one using the wording “Medz Yeghern,” and the other, the wording “Armenian Genocide.” In one textbook, the first mention of “Medz Yeghern” appears within the theme of Armenian language and invention of the Armenian alphabet. The reference is intended to express the value and spiritual implications of the language, calling forth the example of the medieval manuscript Mšo čaŕntir and the door of the Mush Araqelots Church, which was carried and brought to Yerevan by Armenian survivors during the Medz Yeghern (Danielyan et al. 2007, 34). The other version of the textbook introduces the topic of the Armenian Genocide within a wider theme of Armenian history, presenting it as an example of a time in the history of the Armenian people when the country was weak and unable to repel invaders.[3] The Armenian Genօcide is mentioned also within the biography of the famous cultural figures, including Martiros Saryan[4] and Komitas.[5]

April 24 is officially recognized as the Armenian Genocide Commemoration Day in Armenia. It is a non-working day. Since April 24 1968[6] people have gone to the memorial in Tsitsernakaberd to lay flowers. Since the mid-1970s the commemoration day starts with an early morning pilgrimage of the government (at the time, leaders of the Communist Party ruling the Armenian SSR) to pay tribute to the victims of the Genocide (Marutyan 2008, 121). The monument complex itself is treated as a ‘cemetery’ and there is observed many ritualistic elements typical to the practice of visiting cemeteries for remembrance the dead on April 24 of each year (Marutyan 2008:125). On the official commemoration day, the people’s “pilgrimage” to the monument in Tsitsernakaberd in Yerevan includes different conferences and exhibitions dedicated to commemoration anniversaries. Books relating to the occasion are published and presented.

All these make the day a “place of memory,” to use the concept of P. Nora (Nora et al 1999:17-50). This specific “place of memory” is an indelible part of school education in Armenia. It is common for children in Yerevan to join their family members on the April 24 “pilgrimage” to the monument. My field observations showed a considerable presence of groups of school children, especially on the following day (April 25), including elementary students, on their way to the monument and its surrounding territory (Marutyan 2008, 125).

Field observations and interviews with teachers conducted over 2011 to 2014 also showed that one or two days before the official memory day, teachers tend to reflect on the theme with a short introductory “speech” (as they named it) as a tribute to the memory of the victims and reflection on the current social situation. They did, however, try to keep the talk very short and in a mild tone, first of all taking into consideration the children’s age and psychology. An important aspect of the research was to discuss the teachers’ discourse.[7] It cannot be claimed, however, that the full range of perceptions and interpretations could be revealed. Neither is quantitative data available. However, provided here are some pieces of the discourse, or those typical, oft-repeated versions of teachers’ practices of interpretation and perception, which affect the teaching process. For example, there can be mentioned an approach that can be summarized the following way: “They are the future citizens of Armenia and should know everything from the beginning and as it was so; no need to hide the cruel reality from them anyway they get to know if not from us, then from outer world.” There were also teachers believing that they should also introduce to the pupils the notion that Armenians have not only been victims of slaughter. According to this approach, teachers try to change the perception that Armenians had no victories during their history, emphasizing cases of resistance and self-defense during the years of the Genocide and future victorious moments in Armenian history.

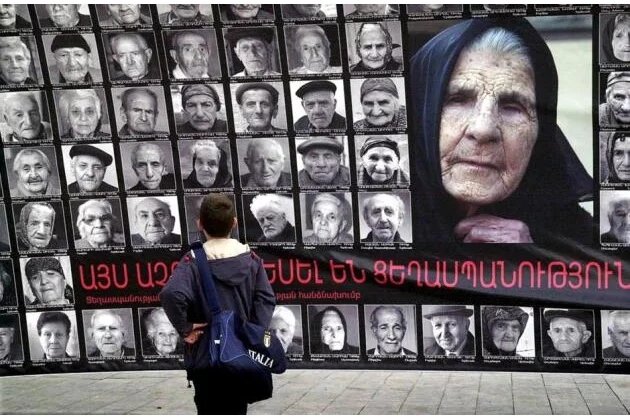

The memory of the Armenian Genocide concerns primary school students through school iconography as well, namely through wall posters, boards and in some cases paintings bearing written and image-based information on the Armenian Genocide, usually with the year 1915 highlighted. They are either prepared by students of higher grades during the learning process, or are posters that have been used for an on-stage or literary event dedicated to the memory of the Genocide. They are not in the classrooms for elementary grades, but in the school foyer or corridors and in sight of the students on a daily bases.

According to the recent field observations, the 100th anniversary commemoration reveals a considerable shift from what used to be, something, which deserves deeper analysis in the future. For example, groups of school children starting from the second year of primary school appear at the Memorial Tsisternakaberd to pay tribute to the victims of the Genocide weeks before the commemoration day (April 24). School iconography includes new items; posters, installations and interior decorations are being created day-by-day to commemorate the 100th year of the Armenian Genocide with inclusion of an official symbol, the flower forget-me-not, and the slogan: “I remember and I demand” in schools (see details at http://armeniangenocide100.org/en/materials/). These and many other newly-emerged practices and rituals are open for future research.

[1] The theme is present in the high school curriculum within a wider context, with more detail provided in the textbooks of the eleventh grade.

[2] The state provides twelve years of free general education for all its citizens. The National Curriculum for General Education introduced in 2006/07 is based on a twelve-year general education programme; compulsory education consists of primary education (grades 1 to 4) and lower secondary education (grades 5 to 9) (UNESCO Report, Armenia 2011).

[3] The text reads: “...The hardest strike the Armenian people received was in 1915-1916. In Western Armenia as a result of the Genocide conducted by Ottoman Turkey the Armenian people were deprived of most of their homeland” (Hovsepyan et al. 2007,15).

[4] The textbook tells of M. Saryan, who, being a patriot, left his life in Moscow and came to Edjmiadzin to assist the refugees who survived the 1915 Medz Yeghern, taking care of the sick and hungry children (Danielyan et al 2007, 120).

[5] About Komitas, an Armenian musician, the textbook says, “Komitas was a great patriot. ...Horrible views of the crime conducted towards the Armenian people in 1915 that Komitas witnessed, impressed him so much, that he felt into the state of mental instability ” (Danielyan et al. 2007,112).

[6] For a long time in Soviet Armenia the theme and memory of the Armenian Genocide had been a taboo, never mentioned in official history. However, family memories were being transformed through oral history as well as in the form of literature and biographic memoires, stories about the childhoods of the writer-witnesses in description of the native lands they left without putting an accent on the descriptions of the actual massacres. These reflections in literature have been replaced with other direct reflections about Genocide in Soviet Armenia. In 1960s the “national theme” has blossomed in Armenia, when mass demonstrations in the streets of Yerevan occurred in April 1965, on the 50th anniversary of the Genocide (Marutyan 2008, 119).

[7] According to the World Bank database, 99.7 percent of primary school teachers (1-4 grades) in Armenia are female (World DataBank 2011). Of the total number of teachers in general education institutions in Armenia, 75.7 percent are aged above 35 (NCET Armenia ... 2011).