This article critically discusses feminist foreign policy and applies a comprehensive understanding of it to Azerbaijan’s foreign policy and the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. While the article explores alternative rethinking of foreign policy, it acknowledges that the pursuit of a feminist foreign policy by Azerbaijan in the near future is not expected. The author rather discusses what feminist foreign policy is, why it is important, and how it can theoretically be applied in the case of Azerbaijan.

Azerbaijan’s foreign policy needs a rethink. The Second Karabakh War in 2020, ongoing hostilities, including Azerbaijan’s aggression towards Armenia in September 2022, and aggressive rhetoric by Azerbaijani officials, not only towards Armenia but most recently towards Iran as well, increase the need for a peace agenda. The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict is one of the priorities of Azerbaijani foreign policy, and analytical and academic discussions around it are usually limited to mainstream approaches to conflict and international relations. However, the slow progress in negotiations, re-occurrence of violence, and increased hatred on both sides show that the mainstream realpolitik approach to foreign relations does not deliver the desired results.

This article offers an alternative reading of foreign policy, which should be understood in the framework of feminist utopia. In the Hobbesian masculinist understanding of the world stemming from the belief that men are like wolves to each other – hostile and dangerous – international relations are chaotic. Everyone is perceived as an enemy, and only a Leviathan-like state can tame the individual evil that is inside us. In contrast, the feminist political imaginary envisages the world as utopias, not dystopias, based on the possibility of comradeship, cooperation, and solidarity rather than hostility. Therefore, feminist foreign policy relies on the understanding of comradeship rather than enmity and cooperation rather than competition.

This article explores the prospects for an alternative foreign policy of Azerbaijan, with a focus on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Discussing the feminist approach to foreign policy in relation to the conflict, the article acknowledges that the adoption of a feminist foreign policy is not expected any time soon in Azerbaijan, and these views are presented rather as alternative solutions to the ongoing processes.

Feminist Foreign Policy: A Critical Review

Many countries in recent years adopted feminist foreign policies. Among them are not only Western liberal democracies but also countries from the Global South, such as Mexico. This trend requires a careful examination of the feminist foreign policies adopted by these countries. The main concern of some feminist observers is that while the feminist approach has great potential for radical change, it has been co-opted by the institutions of the hegemonic patriarchal system, which has not always been accommodating to feminist movements and academia, where these ideas emerged from.

At different periods, some directions of the foreign policies of Canada, Sweden, and France claimed to be feminist, advocated for the integration of women and girls into the decision-making, and centered policies around their needs. They also claimed to be intersectional and considered oppression from different standpoints. However, these foreign policies mostly prioritized women’s participation, representation, and gender equality in their relations with foreign states, without addressing the systemic roots of gender oppression. Moreover, they continued to sponsor or cooperate with authoritarian governments oppressing their own people and women in the first place. One of the vivid examples is Sweden – while claiming a feminist foreign policy, Sweden is among the 25 largest arms exporters. Sweden’s top three arms recipients are Pakistan, the United States, and Brazil – countries with significant women’s rights limitations, such as restricted access to abortion (U.S., Brazil), honour killings, and child marriages (Pakistan). Another example is Mexico. While pursuing a feminist foreign policy, on the domestic level, Mexico continues to downplay the gender-based violence in the country.

Consequently, the critical question is whether there is a potential for going beyond the feminist foreign policies currently applied by states and instead employing a more comprehensive approach. Such an approach requires re-thinking the main concepts such as state, enemy, and peace/violence based on the feminist principles of non-binary thinking, cooperation/solidarity, care, and bridging the personal with the political.

Feminist states – wishful thinking or transformation? The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the COVID-19 pandemic intensified the debates around the crisis of the globalized agenda and the importance of nation-states as the most effective formation instead of regional (i.e., EU) or global institutions (i.e., UN, WHO). These developments require rethinking the power dynamics between gender, patriarchy, and the state. Feminist literature on international relations and state theory has differing approaches to the discussion. While some believe that states can be transformed and become less patriarchal and emancipatory for their citizens, others argue the opposite – states cannot be reformed, as patriarchy is rooted in the concept of the state. For example, some grassroots movements do not enter the state apparatus and create alternative platforms for political action and challenge local politics.

In such a context, grassroots activists in Armenia and Azerbaijan should identify whether they want to cooperate with the state in the context of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict or build alternative spaces for dialogue and pursue an independent agenda that better serves the purpose of peace.

Overcoming dichotomies. Feminist literature opposes binary and dichotomic thinking and rather sees problems as continuums. Hence, peace is not only the absence of war but a broader concept, including peace during wartime or violence during peacetime, such as domestic violence. Feminist literature also rejects the division between the personal and the political, claiming that any personal problem is political, requiring collective resolution. The same is applied to the foreign/domestic dichotomy. Therefore, overcoming the binary thinking which separates foreign and domestic policies is essential. As we see in the example of Mexico, the implementation of a credible feminist foreign policy should start with a feminist approach to domestic policies. Hence, in the case of Azerbaijan, commitment to eradicating violence on the domestic level can be the first step towards a feminist foreign policy.

To summarise, feminist foreign policy has potential beyond mainstream co-optation in the form of women’s integration into the existing system under the name of their emancipation. Such potential requires a critical analysis of the state and its role in international relations, identifying other forms of violence and oppression besides physical violence during war, and thinking beyond the dichotomic distinction to bridge the personal and political, peace/war, foreign/domestic into a continuum.

Feminist Foreign Policy in Azerbaijan: The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict

The integration of women into negotiation processes reflects the common understanding of the feminist foreign policy in the South Caucasus. The previous section discussed the possibility of thinking in feminist terms beyond the integration of women into the established systems. In the context of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, bringing women to the table of negotiations will not radically change the discourse of the states or offer an alternative solution to the conflict unless we commit to critical peace and trust-building among people. Hence, this section discusses the feminist alternatives to the current peace process.

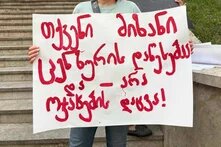

The fragile peacebuilding process was one of the first victims of the second Nagorno-Karabakh war and still awaits its re-animation. After the war, the institutionalized peacebuilding community almost disappeared. Only a group of non-established young activists, mainly from feminist and leftist ideological worldviews, voiced their opposition to a vast majority of people who support the idea of a military “solution.”

In general, there is a massive mistrust of peacebuilding and peacebuilders, negotiations, and diplomatic resolution of the conflict in the wider Azerbaijani society. The authorities, political analysts, and general public opinion were increasingly convinced that the negotiations process and peacebuilding efforts failed for 30 years. In Azerbaijan, this was used to legitimize the war.

Admittedly, careful examination of the negotiations process starting from 1992 (establishment of the OSCE Minsk Group) and peacebuilding activities from the 1990s leave us with few tangible results. The negotiations process over the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict was one of the most closed and secretive peace processes. The track two peace process conducted by civil society was not supported by an effective track one process on the level of officials. Usually, civil society representatives who participated in dialogue meetings and advocated for peace were perceived as traitors or agents of foreign interests. Another reason for the unsuccessful peace process was its detachment from local voices. After the collapse of the USSR, the region became another market for liberal peacebuilding, the rule of law, and democratization projects. In the following decades, civil society became mere implementers of the liberal peace agenda, gradually depriving local communities of their agency and voice. Over time, civil society became elitist and detached from the communities and their needs.

Thus, civil society actors could not build genuine trust between the conflicting parties. Only a limited number of individuals with shared values and ideologies trusted each other and objected to the 2020 war. After the war, these individuals grouped, and small grassroots peacebuilding and dialogue initiatives emerged, such as Caucasus Talks, Caucasus Crossroads, Bright Garden Voices, Post-Soviet Peace, and Feminist Peace Collective.

In such a context, feminist foreign policy can offer an alternative imagining of the peace process and discourse. In a different Azerbaijan, the principles of feminist foreign policy could be applied around the following issues:

-

De-militarization of the official discourse, education policies, and broader societal dynamics instead of building new military parks, exalting fallen soldiers’ photos, or glorification of war on public TV/radio, etc.

-

Re-orientation of state budget funds in favour of social issues.

-

Supporting the funding of and not limiting grassroots-led peace and dialogue initiatives by the state and international organizations.

-

Joining and supporting global peace and solidarity by the state.

Demilitarization. Militarization is not only armament but also cultural and material preparation for war, such as hostile and aggressive discourse, material symbols, education, and media coverage. In Azerbaijan, after the Second Karabakh War in 2020, the militarization of the official discourse increased, followed by the opening of new military and victory parks and monuments. This process is also supported by militarized education and state-controlled media coverage.

Applying feminist foreign policy in this context implies a demilitarization process starting from internal policies of decreasing the domestic military symbols and the hostile rhetoric, which can naturally lead to a decrease in military funding and disarmament on a foreign policy level.

Re-orientation of funds. Since funds are never endless, the prioritization of war and military or law enforcement institutions decreases the opportunity for social services and other spheres to develop. A decrease in military spending can be achieved only by rethinking international relations. The realist understanding of international relations, the prevailing worldview, assumes threats and enemies on the international level. While not advocating for ignoring real threats, Azerbaijan should change its foreign policy vision from enmity to comradeship. Currently, based on the enmity vision, the domestic discourse and media propaganda produce hostile rhetoric and environment. Rethinking the securitized discourse around the threats in the region and turning the discourse into comradeship rather than enmity can decrease the need for securitization and funding military and law-enforcement agencies, which consequently can lead to re-orientation of funds to social and more immediate needs.

Grassroots-led peacebuilding. As mentioned above, several grassroots organizations emerged after the war. They do not have a wide audience, but these groups came together without any external support, which was not the case for many years. This was voluntary self-organizing by young people sharing the same values and worldview. Peacebuilding led by these groups has greater potential as they share the same values, are organized voluntarily, and do not have a hierarchy between them and local communities. A feminist foreign policy would suggest supporting such groups, providing them with broader space, and cooperating with international organizations to involve them in peacebuilding activities.

Solidarity. The concept of transnational solidarity is important because changes in the vision from enmity to comradeship can be achieved only as a collective effort. Individual states cannot pursue a friendly relationship with states that reject it. Therefore, adjusting foreign policies in the direction of joining global struggles and showing solidarity in cases of aggression or violence should be a priority for the Azerbaijani state rather than pursuing a neutral strategy. In a broader understanding of solidarity under a feminist foreign policy, selling arms or any other cooperation with states that oppress their own people or, even worse, have imperial ambitions and oppress others should not be supported.

To summarise, feminist foreign policy in the context of Azerbaijan is a long-run utopia. While the hostile political environment does not leave a chance for alternative political imaginations to emerge and spread, such discussions open a prospect for non-binary critical thinking regarding foreign policy. This can stimulate solutions for ongoing problems that have never been discussed or thought of by the authorities.

The content of the publication is the responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to express the views of the Heinrich Boell Foundation Tbilisi Office - South Caucasus Region

Bibliography

-

‘A Vision for A Feminist Peace Building A Movement-Driven Foreign Policy’ (Grassroots Global Justice Alliance, MADRE, Women Cross DMZ 2020) <https://www.feministpeaceinitiative.org/pdf/index/visionfempeace.pdf> accessed 2 November 2022

-

Daniela Philipson Garcia and Ana Velasco, ‘Feminist Foreign Policy: A Bridge Between the Global and Local’ (Yale Journal of International Affairs, 2022) <https://www.yalejournal.org/publications/feminist-foreign-policy-a-brid…; accessed 1 November 2022

-

Elizabeth Fuller ‘Azerbaijan’s Foreign Policy and the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict’ 2013. <https://ciaotest.cc.columbia.edu/wps/iai/0028455/f_0028455_23134.pdf> accessed 2 November 2022

-

Emma Klever, ‘The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan: An Overview of the Current Situation’ 2013. European Movement. <https://europeanmovement.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/2013.09-Current-…; accessed 2 November 2022

-

Gamaghelyan P, ‘Caucasus Edition: Decentralized Transnational Network as a Pivotal Structure for Peacebuilding in Non-Democratic Environments’ 2022. Action Research 147675032110705

-

Martha Delgado, ‘Mexico’s Feminist Foreign Policy’ (Martha Delgado - una política con causa) <https://martha.org.mx/una-politica-con-causa/mexicos-feminist-foreign-p…; accessed 1 November 2022

-

Merlyn Thomas, ''‘Sweden ditches ‘feminist foreign policy’'' 2022. BBC News. <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-63311743> accessed on 16 November 2022

-

Nancy Fraser, ‘Feminism, Capitalism And The Cunning Of History’ 2009. New Left Review 97

-

Pieter D. Wezeman, Alexandra Kuimova And Siemon T. Wezeman, ‘Trends In International Arms Transfers, 2021’ (SIPRI 2022) Fact Sheet <https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2022-03/fs_2203_at_2021.pdf> accessed 1 November 2022

-

Scott Burchill, Andrew Linklater, Richard Devetak, Jack Donnelly, Matthew Paterson, Christian Reus-Smit and Jacqui True, ‘Realism’, Theories of International Relations 2005. Third Edition, Palgrave Macmillan

-

The Swedish Foreign Service Action Plan for Feminist Foreign Policy 2019–2022, Including Direction and Measures for 2020. https://www.government.se/499195/contentassets/2b694599415943ebb466af0f…c/the-swedish-foreign-service-action-plan-for-feminist-foreign-policy-20192022-including-direction-and-measures-for-2020.pdf accessed on 16 November 2022

-

Thomas de Waal, ‘Remaking the Nagorno-Karabakh Peace Process’ 2010. 52 Survival 159

-

Thomson J, ‘What’s Feminist about Feminist Foreign Policy? Sweden’s and Canada’s Foreign Policy Agendas’ 2020. 21 International Studies Perspectives 424

-

Vadim Romashov, Nuriyya Guliyeva, Tatia Kalatozishvili, Lana Kokaia, ‘A Communitarian Peace Agenda for the South Caucasus: Supporting Everyday Peace Practices’ 2018. 3 Caucasus Edition 8

-

Väyrynen T and others (eds), Routledge Handbook of Feminist Peace Research. 2021. Routledge.