Discussing the example of Tbilisi, the author analyses some of the major challenges facing contemporary urban policy in Georgia, as well as the evolution of ideas and forms of protest that urban movements deploy to address them. The article also provides – in light of the state of democracy in Georgia – an overview of recent urban protests, major trends in how they changed over time and the problems they faced.

The engagement and the quality of participation of citizens in state and institutional processes is the ultimate yardstick of democracy. The main criterion is the impact of public participation on administrative decision-making and the sway citizens’ priorities hold over the formulation of state policy. David Harvey’s concept of “the right to the city” describes a state of democratic development, in which citizens on the local level are directly involved in improving their residential environment. In a sense, such involvement, shaped and nurtured daily by urban movements, neighborhoods and local communities, is the most tangible, quotidian form of democratic governance.

Urban movements are a recurring feature in Tbilisi’s history, but an exploration of their trajectories reveals not an example of democracy, but its crisis. In Georgia, supporting commercial interests by ignoring the will and the interests of the public and overcoming public opposition through campaigns directed against social movements are a shared legacy of different governments over the years that differ only in methods and tendencies. Replacement of one government with another in 2012 brought with it only new forms of exclusion of civic society from the decision-making process: the pursuit of private interest at the expense of public good intensified. In response, urban movements and their forms of protest had to evolve.

Challenge 1: Chaotic Economic Development

A chaotic real estate development boom in Georgia’s larger cities dates to the early 2000s and has been in full swing since 2006, supported by hefty privileges for the industry and freedom from regulatory constraints. The unravelling of the historically formed fabric of the city, the occupation of green and recreational spaces by unchecked construction, and the superimposition over cultural heritage sites of ad-hoc “euroremont” structures served as shortcuts designed by the government on the way to economic advancement. It is in this period that it became acceptable to build anywhere and at any cost. Neither the value of the territory, nor the historic significance of impacted buildings, can halt construction under the banner of “development.” Environmental considerations and the invaluable attachment of neighborhood communities to the identity of the city are equally ignored. Construction permits are issued everywhere – even in areas where heritage status or environmental concerns seem to preclude the possibility of aggressive interventions.

In 2010, construction began on the central highway that cut through the middle of Mziuri Park in the Vake district of Tbilisi; at the same time, residential apartment complexes were planned and built in the adjacent basin of the Vere River. Similar projects were initiated in the historical Old Tbilisi districts. New development threatened the understated pride of the city – Gudiashvili square. Unregulated development even resulted in a hotel project springing up in Vera Park, beloved by generations of Tbilisi’s residents. Thus, creeping construction transgressed all boundaries of the city.

Response 1: The First Wave of Urban Movements

In response to these developments, public anger and protest began to simmer, later giving rise to the first wave of urban movements. Campaigns like Save Mziuri, Protect Gudiashvili, Saving Vake Park and others had mobilized groups of residents in the affected central districts to protest. Activists such as Hamkari, Guerilla Gardening and other groups, grew popular, adding to this wave. They articulated their positions in reference to universal environmental values, while threading their public messaging through notions of individual environmental responsibility.

These protest campaigns voiced concern about the loss of the city’s identity. They organized street festivals, art events and collective gardening. The messaging usually revolved around the protection of a specific location and these progressive demands attracted many in their communities and across neighbourhoods. That these protests concerned some of the most popular, identity-defining and beloved places in Tbilisi helped mobilize the public. They attracted people outraged by the numerous threats that development posed to their favorite places in the city. It is also important to note that the forms of protest chosen – campaigning through festivals – were novel and exciting to most Tbilisians. These factors helped propel the first wave of urban protests.

Challenge 2: The Real Estate Industry in Government’s Clothing

2012 heralded the first peaceful transition of power in Georgia. The new ruling party was vocal and aggressive in its critique of the economic, political and cultural policies of its predecessor, the National Movement party. On urban issues, Georgian Dream promised to prioritize environmental considerations and the protection of cultural heritage. It declared that it will not repeat the mistakes of the previous government and will not allow construction to take place in Vake Park or the Gudiashvili Square.[1] A public reversal of the ruling paradigm and the unity of urban activists, as well as permanent campaigns in the courts and on the street, did make it possible to save these parks from construction. But Tbilisi’s urban movements soon faced familiar threats in new forms.

Corporate forces, entrenched within the government, had continued to seek support for their commercial projects and had mobilized the entire administrative capacity to this aim. The case of the Sakdrisi Gold Mine, albeit taking place out of the city, became the first episode that undermined the new government’s embryonic recognition of its environmental responsibility. As RMG Gold, a company directly affiliated with the leaders of the ruling party, prepared ground for a resumption of operations in Bolnisi, including within the territory of an ancient mine. The Ministry of Culture, municipal governments, the Government of Georgia and the entire state apparatus worked in unison – and in breach of legal norms and regulations – to support the mining company.

In 2013, a company affiliated with Bidzina Ivanishvili, Georgian Dream’s founder known as the informal ruler of Georgia, initiated a massive, contextually disproportionate project – Panorama Tbilisi, consisting of number of upscale residential and commercial developments in the city centre and the hills above, connected by cable transit. The decision-making process around Panorama Tbilisi proceeded in the context of total public opposition and substantive restrictions placed on public participation. To limit the involvement of civil society, the government re-assigned the responsibility to approve the project from the Tbilisi City Hall to the Ministry of Economy and the move helped sidestep stiff resistance by professionals who had access to participatory bodies within the City Hall and the City Assembly. The Ministry proved to be impenetrable for the project’s opponents. At this point, it became clear to urban activists that the new government had chosen to remain loyal to the policy of chaotic urban development initiated by its predecessor; the government worked hand in had with powerful corporate forces giving them full support – a circumstance that will later contribute to the weakening of the ability of the civil society to resist.

Response 2: The Second Wave of Urban Movements

The unmasking of the true nature of the new government, as well as the discovery of direct and substantial commercial interests of its representatives, expressed in pernicious and illegal urban development projects, meant the rekindling, with renewed urgency, of the long-standing threats to the city. Tried and tested campaigning methods of urban movements – organizing festivals and street protests, emphasizing individual environmental responsibility – began to seem inadequate. In the face of this new crisis of democracy, urban movements were revealed to be especially vulnerable. At this inflection point, fragmented urban movements and activist groups spent a lot of time analyzing past mistakes and critiquing the forms and content of past campaigns. In the process, new and relatively well-organized alliances of like-minded groups began to take shape. Young, left-leaning activists filled their ranks. Their messaging transcended exclusively urban and environmental issues and incorporated attempts to re-articulate urban problems from a social perspective. They demanded the addition of social issues to the agenda and relied on explicitly leftist imagery, integrating social and environmental themes. When placing responsibility, they pointed the finger at unregulated capital. In contrast to their critique that took aim at the totality of the social system, established movements of the past had preferred zooming in on particular issues and building campaigns around specific concerns, relying on a narrowly conceived, issue-specific argumentation and a corresponding plan of action.

The divergence of old and new urban movements was most pronounced in the struggle against Panorama Tbilisi. As part of this campaign, diverse activists formed a united front and established a broad coalition Ertad (United). The coalition organized a single, but crucially important demonstration, a march that opposed the rampant disruption of Tbilisi’s historic district as the result of new and unseemly development projects in the city centre and the hills above. This demonstration turned out to be the last example of a united effort by the activists of the old and new waves. The demonstration revealed the inertial nature of the alliance and an ongoing process of ultimate fragmentation, as well as significant disagreements over ideas and ideology, forms and content of protest. In the aftermath, it became impossible to put together a strong and united protest front against Panorama. Perhaps even a united front would have been unable to resist a cohesive and forcefully mobilized joint interests of the state and capital. The giant main building of the project is now wedged into the heart of Tbilisi’s historic centre.

Challenge 3: The Restriction of Participation and the Simulation of Responsibility

The municipal elections of 2017 led to turnover in the Tbilisi City Hall. From this point forward, it became clear that the national government assigned responsibility for addressing urban campaigns and protests to the municipality. The environmentally focused electoral campaign of the new mayor, Kakha Kaladze, replete with notions of care for the city, is a clear proof of this dynamic. According to Kaladze’s campaign, the mayor fully recognized the importance of protecting green spaces and the city’s cultural heritage, admitted to past mistakes (excluding Panorama Tbilisi, which he supported publicly on multiple occasions, arguing that it is a progressive business project) and promised their remediation.

On the political agenda, urban issues clearly moved from the purview of the central government to that of the local municipality. As a confirmation of his commitment to his campaign promises, Mayor Kaladze vowed to abolish the Zoning Council. The Zoning Council was a consultative body within the City Hall that was directly and immediately implicated in the most egregious decisions fueling Tbilisi’s chaotic urban development. Representatives of the real estate industry, who held majority in the council, had been unhindered in shaping zoning laws, adjusting permitting coefficients, making decisions that allowed for unchecked construction with little to no regard for public interest and opinion. Despite all this, the Zoning Council retained some space for public participation. When they were able to overcome resistance and barriers imposed to limit their involvement, members of the public were able to voice their arguments at the sittings of the Zoning Council.[2]

After the Council was abolished the mayor set up no substitute bodies to ensure effective and flexible public participation. The Architecture and Urban Development departments now publish information regarding some of their decisions online, which is supposed to support public participation in the decision-making process. But using the municipal website requires technical expertise, competence and professional connections among Tbilisi’s architects. It is even more troubling that City Hall had almost abandoned the practice of arranging public sittings to discuss construction permits, which meant that citizens are made aware of certain municipal decisions, including the issuance of construction permits, only after the fact.

As he was shutting off public participation mechanisms, the mayor declared the protection of Tbilisi’s green spaces his policy priority and embarked on renovating existing public squares and parks. Such works are still, at the time of writing, commonly undertaken without the involvement of local residents, and often with no project plans at all.

Unfortunately, the urgency of issues regarding Tbilisi’s urban ecology did not prompt the government to address the pressing concerns. Instead, it led to the creation of a simulated sense of responsible governance.

Response 3: Neighbourhood Activism

In response to the shift of urban policy making from the central to the local government, activism, too, went local. At this stage, a new, embryonic channel of resistance appeared in the form of neighbourhood activism. Neighbourhood communities suffering as a consequence of some of the most egregious decisions by the Zoning Council began independent campaigns for safeguarding their urban environment. In contrast to urban movements of the past, these neighbourhood groups lacked recognizable public figures, consisting of regular citizens standing up for their communities. Their main instrument was public and vocal resistance to the decisions of the policymakers and a personal, emotive and visceral articulation of their opposition.

It was this kind of neighbourhood activism that made it possible to protect a crucial environmental resource – the Dighomi Forest Park. A company with ties to the government had planned to construct a massive high-end residential building on a plot bordering the park. Mayor Kaladze was direct in his criticism of the Young Greens who had come together to protect the park. The activists, through voicing their concerns in an organized and systematic way, were able to mobilize a large group of residents and members of the local community, turning the case of the Dighomi Park into a re-invigorating spark for the emaciated activist scene. The City Hall retreated and scrapped the planned project.

Despite this success, neighbourhood activism still faces the problem of the intermixing of municipal and corporate interests. Where corporate projects can count on political support, activists find it harder and harder to engage in effective forms of resistance. A neighbourhood community group has been demanding a place at the table in the decision-making process regarding the Soviet-built Hippodrome grounds since City Hall announced its rehabilitation project in 2020. Its opponent in this struggle is not just Tbilisi City Hall, but also the Cartu Foundation, closely affiliated with the ruling party. A neighbourhood group in a different stretch of the same Saburtalo district, along Vazha Pshavela avenue, is facing similar problems. There a recreational space has been paved over in the name of renovation, covering mature plants with cement. Noone consulted the local residents. Of course these cases present a small sample of active (at the time of writing) neighbourhood groups campaigning in Tbilisi.

With a View to the Future, and as Best We Can, We Refuse to Give Up Our Right to the City

Observation of the rise and transformation of urban movements in Tbilisi shows that they evolve in response to the degradation of democratic institutions and the diverse forms of preempting public resistance deployed by the government. The government has the capacity to alter the course of reactive movements and responds with its own set of strategies. Despite scattered examples of success, in the long run, the government successfully stifles dissent. Considering the state’s total disregard of democratic norms, it is difficult for urban movements to find a recipe for effective action. But one strategy they have yet to try is that of developing an independent agenda and of moving from a reactive to a proactive regime of campaigning. Such a strategy is not without its own challenges – proactive campaigns require adequate preparation, human and financial resources, unity, effective organizing and the existence of democratic spaces. Georgia’s local and national governments are encroaching on the latter day by day.

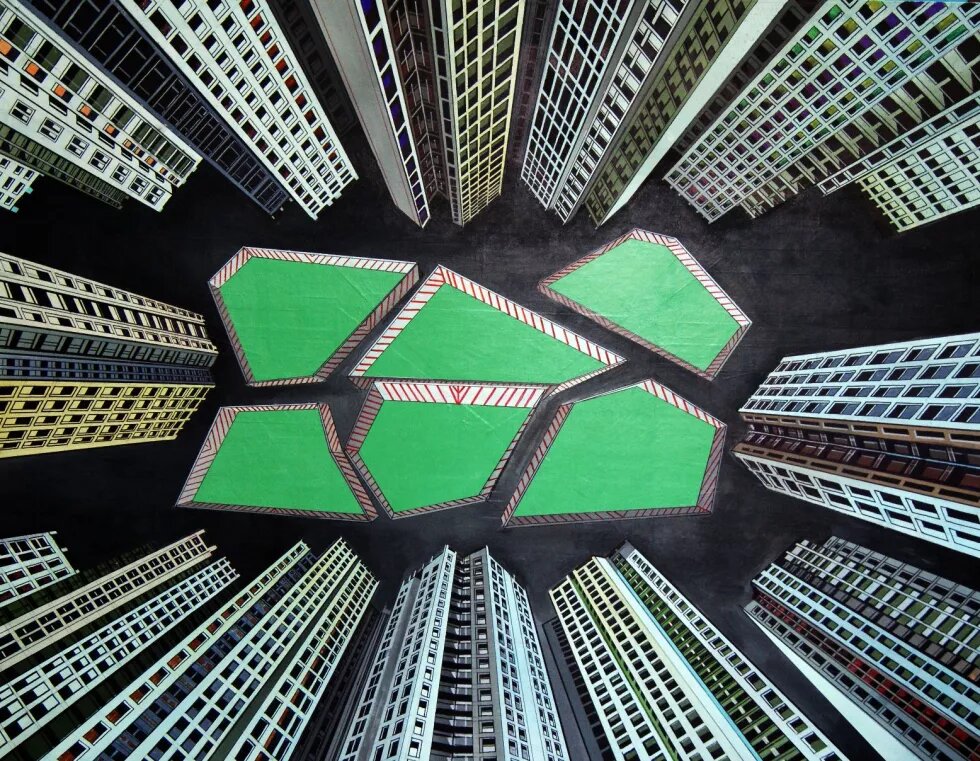

Tbilisi is facing new and alarming threats. Just days before the publication of this article, Tbilisi’s City Assembly greenlighted a plan to permit the construction of several new skyscrapers in, among others, Tbilisi’s historic district. The Assembly approved the simultaneous construction of the massive projects without considering the potential impact of the skyscrapers on environmental conditions, the already noticeable deficit of social and medical infrastructure and the city’s transport network. The approval of the plan, especially the development along Tbilisi’s right bank, according to experts, will wholly overwrite the city’s traditional identity and its aesthetic legacy. The construction of skyscrapers at Heroes Square that will overshadow the spectacular Soviet-built Laguna Vere public swimming pool complex and the 19th century red-brick building of the former silk factory, is a project once again linked to Georgia’s informal ruler Ivanishvili and is among the projects approved by the Assembly. The mobility and transit crisis already evident in the area is predicted to worsen, should the plan be carried out.

The Assembly made its decision on the skyscrapers abruptly and in the middle of August, when a large portion of Tbilisi’s residents usually leaves the city. Some activists were barred from attending the hearing altogether, while those who were able to listen in left under the impression that the decision had been made well in advance of the hearing and that their arguments could have no impact on the Assembly’s decision. All of this is happening because Georgia’s informal ruler is either personally involved in the approved project, or some other corporate actor is able to call on unlimited political support.

It is difficult to assess what form of resistance could have a chance of success against threats of such magnitude. Despite decades of exclusion, repression, and derision, Georgian civil society continues to assert its right to the city.

Content of the article is the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Heinrich Boell Foundation Tbilisi Office - South Caucasus Region.

[1] These promises were made at several public meetings. They were not reflected in the action plan of the Government of Georgia, but their electoral program referenced the goal of sustainable development. It was these promises that later shaped the rehabilitation plan for Gudiashvili Square.

[2] Nutsubidze 77 Square; the square on Tamarishvili avenue; green space located near the university campus on Kavtaradze Street.