Metsamor Hotel, built in the early 1970s to house employees of the Armenian nuclear power plant, is now overcrowded with refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh. This photo story by Khachatur Tovmasyan tells the stories of people who were forced to leave their homes and are yet to see a brighter future.

Built between 1972 and 1975, the Metsamor Hotel was intended to house employees of the Armenian Nuclear Power Plant. For many years the building was unfit for habitation due to its dilapidated condition. During the Second Karabakh War in 2020, the municipality of Metsamor renovated the building to provide shelter for displaced families from Artsakh. The hotel rooms, designed for two people, are now overcrowded; each room accommodates 4-5 people. In total, about 120 displaced people live in the hotel.

“I’d been working as an accountant in Karabakh since 1975. At the time, Zhorik had just returned from Moscow and was looking for a bride,” Karine recalled. “We had a mutual acquaintance who said: “If you want to get hitched properly, I would advise you to find this girl from the neighboring village and win her hand.””

“Ah! That’s how I was forced to marry her, willy-nilly,” Zhorik smiled.

“I was an attractive and well-dressed girl then. My teeth were gold.”

Karine and Zhorik moved to Metsamor from Artsakh a few days after the war broke out, on 19 September 2023. Their daughter Marine moved to Metsamor three years ago. She lost her husband during the 44-Day War in 2020. When the war started, Marine’s husband asked her to leave Artsakh with the children and stay in Armenia until the war ended.

Since 2022, the Metsamor Hotel has become home to people from Artsakh. Over the past three years, some of them managed to return to Artsakh and move to a new house, until a new war forced them to leave their homeland again and come back to Metsamor ‒ this time with no hope of ever returning. The Republic of Artsakh will cease to exist on 1 January 2024.

“My husband lost his leg during the First Karabakh War, in 1992,” Karine continued. “We were afraid that once the Turkish border guards started questioning us, they would realize that Zhorik was a war veteran and wouldn’t allow him to cross the border. We thought it would be right for him to drive the car past the military outpost on the Hakari Bridge and thus go unnoticed. That’s what happened. We were told to walk, while my husband crossed the bridge by car. I covered his legs with a jacket so that they wouldn’t notice anything and ask questions. There were fears that men who had participated in the war would not be allowed out of Artakh, so we were lucky.”

“Things were different back then. There were many Turks [Azerbaijanis] in the village. Our poultry farmer was a Turk, a golden boy, we were very close. I don’t believe he could do anything wrong. He left as soon as the war started in 1992. The Turks forced him to leave. We haven’t heard from him since then… Now my son is calling us to Russia, but I cannot leave my grandchildren. It’s impossible for me not to stay by their side. My daughter’s husband died in the 2020 war. How can I leave them now?”

Marine was sitting at the edge of the bed, holding her little boy Taron in her arms.

“My husband is buried here in Metsamor,” said Marine. “I visit his grave at least two or three times a week. My husband’s friends wanted to bury him in Karabakh, but I didn’t let them. I had a dark sense of foreboding. Now our cemeteries there are probably all destroyed.”

“My dad has a million medals, you know? ” said Tigran, Marine’s eldest son.

“We couldn’t take the medals with us, we left them there,” Marine continued, “so that the border guards wouldn’t find them. We just renovated our house, I have no idea what it looks like now. It’s probably occupied by Turks now.”

“We didn’t have just one house, look how many properties we owned,” Karine said, pulling the title deeds out of the drawer one by one. “They were all ours.”

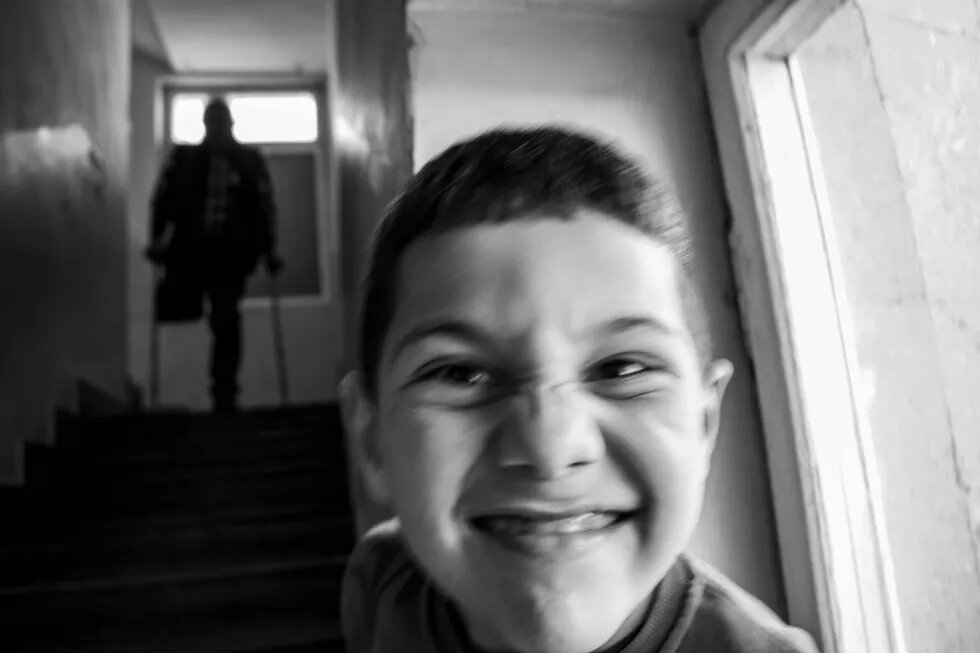

In the corridor, the ashtray was filling up fast; the men sitting on the old sofa were smoking quietly and passing the single ashtray to each other. The sun was warming up the bare floor. Dust particles were glistening in the sunlight, swirling with the smoke. Children’s voices were echoing through the empty corridor ‒ a poignant reminder of a childhood left at the bottom of the gorges. Everyone’s thoughts turned to their village, garden, yard and home.

“It’s difficult for a person who has devoted his life to cultivating the land to stay within four walls,” said Slavik. “Everything grew in our garden. We had a cattle shed and produced everything we needed: fruit, vegetables, cheese, milk, yogurt, etc. In one day we lost everything we’d created for years. Now I have to start all over again, although at my age it’s hard to do so. I smoke a lot out of idleness. I need to find a job, I can’t live like this anymore.”

The children bustled towards us.

“Stop running, Taron, you’ll sweat,” Marine said angrily.

“Watch what I’m doing,” Taron said, jumping and spinning in the air.

“Where did you learn that skill?”

“In gymnastics class. I need to practice a lot. I want to be a policeman.”

“And what are you going to be, Tigran?”

“A pilot.”

“And I’m going to be a football player. Come on, I’ll show you our football pitch,” Karen said and ran out of the building.