In the article, the author analyses the current practices of pesticide usage, examines the challenges faced by consumers and producers, and presents his vision for short- and long-term regulations of pesticide usage in Georgia.

Pesticides are agrochemical compounds whose main purpose is to eliminate pests. Agricultural products, as well as stored harvests, need protection from three major types of threats, like disease, insects and weeds, as well as nematodes and rodents. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), on average, 40% of agricultural products are lost due to pests, threatening the food security of the world’s growing population. At the same time, the unsustainable use of pesticides harms the environment, biodiversity and human health. At this stage of agricultural development in Georgia, when the sector is transitioning from extensive to intensive production, it is crucial for farmers to adopt rational practices of using these toxic compounds. The issue is even more important in the context of Georgia’s aspiration to join the European Union, which prioritises food safety, labour rights, waste management and the protection of the environment and biodiversity.

Pesticides and Georgia’s Agricultural Industry

Agriculture plays an important role in Georgia’s socio-economic development. According to official statistics, almost one-fifth of the country’s active population is employed in this sector. Since the fall of the USSR, agriculture has been a major source of subsistence and income for Georgia’s rural population.[1] Georgian farmers mostly produce grains, fruits, vegetables, dairy and meat.[2] Storage, processing and other value-added systems are still not sufficiently developed. There are ongoing efforts to introduce international standards and certification programs, while the regulatory framework and its enforcement are weak. Productivity is very low[3] (even compared to other countries in the region), which is explained by a number of factors, including the predominance of smaller plots and the lack of agricultural education. Additionally, agricultural jobs are among the lowest paying and the sector is therefore not competitive. Due to rapid urbanisation and high rates of emigration, young people are leaving villages and moving away from agriculture, making it increasingly more difficult to find qualified personnel and develop the agricultural business.

Due to the low purchasing power of Georgian consumers and the factors mentioned above, bio-organic businesses are rare and this area of agriculture is still embryonic. The main products that are bio-certified are exported wine, wild fruit/herbal tea and small amounts of natural honey.[4] Contrary to the common belief that we primarily consume "ecologically clean" fruits and vegetables in Georgia, the reality is that most local agricultural products undergo processing with pesticides.

According to the Law of Georgia On Pesticides and Agrochemicals, pesticides are “chemical or biological preparations used against plant diseases and their vectors, pests and weeds, against diseases of stored agricultural products, pests, rodents and zooparasites , as well as for the regulation of plant growth, for the removal of leaves from plants prior to harvesting (defoliants) and for drying plants (desiccants), for disinfecting storage facilities, warehouses, transport facilities, greenhouses, soils, products of plant origin and any other products subject to phytosanitary control.”[5] Some pesticides, mainly those based on organic compounds or copper/sulphur solutions can be used in bio-organic production, but most pesticides imported and used in Georgia are synthetic. Legislation and regulations set identical requirements for both types of pesticides, regardless of origin.

According to GeoStat, from 2006 to today, pesticide use in Georgia has increased five-fold and the total area treated with pesticides, including forests and other types of productive land, has reached 3 million hectares.[6] In 2022, farmers applied pesticide to 70,000 hectares of perennials and 47,000 hectares of annual plants.[7] The government also uses pesticides. In 2023, it treated 227,148 hectares of land just to control the stink bug (Halyomorpha halys) infestation in western Georgia.[8] The government also treats land in eastern regions as part of the campaign to control locust infestation (under the program: Combating and Supporting Control of Locusts) In 2022 it treated more than 90,000 hectares for this purpose.[9] The government also encourages farmers to use pesticide against rodents.

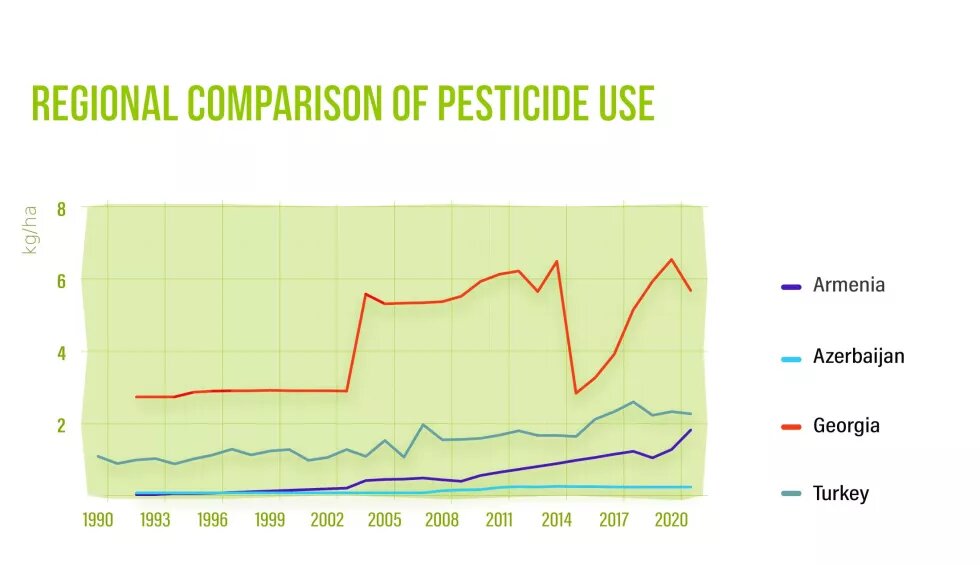

On average, Georgia uses more pesticide per hectare than other countries in the region, including Armenia, Azerbaijan and Turkey.[10] Of these countries, only Georgia has signed an Association Agreement with the European Union and has become, along with Turkey, a recognised candidate for membership. This means that Georgia’s laws must approximate and comply with those of the EU, including on the use of pesticides.

Diagram 1: Regional Comparison of Pesticide Use Per Hectare (kg/ha)[11]

The Farm to Fork Strategy, a part of the European Green Deal, stipulates that the use of hazardous pesticides and associated risks must decrease by 50% by 2030.[12] This objective contradicts the trend of increasing pesticide use in Georgia. Georgia is not a signatory to the Farm to Fork Strategy, but to ensure that Georgian products can be exported to the European Union, we must comply with its requirements and standards of production.

Diagram 2: Fungicide, Herbicide and Insecticide Use in Georgia[13]

Practices of Pesticide Use in Georgia

It is widely known that pesticides harm the environment, biodiversity and ecosystems. At the same time, these chemicals pose a threat to food safety. People who are directly exposed to pesticides are especially vulnerable.

The process of using agrochemicals generally involves these steps:

- The process begins with the purchase of an agrochemical compound in a store. A pesticide can be sold in various forms, including in the form of a powder, liquid, gas, paste, briquette, granules, gel, emulsion, and concentrate.

- The second stage involves the transportation and storage of pesticides. Farmers often buy and store an entire season’s stock of agrochemicals in a single purchase. Sometimes they buy for a single use.

- The most common method of applying a pesticide involves dissolving it in water and spraying the resulting solution. In the best case, empty pesticide containers (plastic bottles, bags, etc.) are thrown into trash cans.

- Pesticide-containing solutions are poured into a sprayer, which can either be small and portable (handheld sprayer) or attached to a tractor (boom sprayer).

- Pesticide is applied to plants to protect them from disease and/or for combating pests that live on the plant.

- At the end of the process, a pesticide sprayer is washed and stored.

Observing the practices of pesticide use in Georgia, several issues related to occupational safety, treatment of agricultural crops or weeds and waste management deserve special attention.

Occupational Safety

Anyone can buy pesticides, including non-farmers, without demonstrating any basic knowledge of chemicals and how to use them. Applying pesticide without proper personal protective equipment (PPE) could lead to significant harm. The extent of harm depends on various factors like the type of pesticide and the extent and duration of exposure. Pesticides can cause immediate and serious negative effects, as well as long-term and chronic problems.

Protective equipment that must be used when working with pesticides include respirators, glasses and goggles covering eyes and the face, chemically resistant gloves, uniforms and rubber boots. High quality PPE is expensive, while work culture at farms often does not include their use. At the same time, the nature of agricultural work means that personal equipment can interfere with breathing and cause, in hot weather, overheating, as well as excessive sweating. PPE can also be generally uncomfortable. As a result, the adoption of PPE in Georgia is almost non-existent. Agricultural plots also often lack even minimal infrastructure, which would have allowed farmers and others employed in agriculture to clean and safely store their PPE after treatment.

Treating Agricultural Crops or Weeds

Pesticide use is an important determinant of the environmental impact of agricultural activities. First and foremost, it is important to regularly check and calibrate the sprayer used in the treatment. Such calibration is necessary for ensuring that the sprayer emits the exact quantity and concentration of pesticide needed for covering target plant surface area with the least amount of concentrate. In Georgia, sprayers are almost never calibrated.

It is also important to focus on the concentration of the pesticide-containing solution - the proportion of pesticide and water that corresponds to the area considered for treatment. Miscalculated concentration leads to ineffective treatment and the need for repeating the procedure; alternatively, it can cause excess toxicity, harming not just the pest, but also the plants.

Since currently the most important source of agricultural extension[14] are vendors behind the counter at agrochemical stores, they have an incentive to sell as much product as possible. They advise the farmers on the choice and concentration of pesticides. Unfortunately, it is common for consultants to advise concentrations far exceeding those indicated on product labels, justifying them with the supposed motive of “increasing the effectiveness” of pesticides.

The timing of pesticide use and environmental conditions like relative humidity, temperature and velocity and direction of wind are important factors that affect the success of treatment and the minimisation of soil and water pollution. Pesticides should be used in the evening, when bees and pollinators are no longer present, and the chemicals will only target the pests.

Waste Management

We must mention that empty pesticide containers, as well as pesticide residue in the sprayer and the wastewater used in cleaning the sprayer are classified, according to the Waste Management Code of Georgia, as hazardous waste and must be managed accordingly.[15] If the total amount of hazardous waste accumulated on a farm during the course of a year exceeds 120 kilograms, the farmer must employ an environmental manager, prepare a waste management plan, ensure the proper training of personnel exposed to hazardous waste and commence separation of such waste. For disposal/destruction, hazardous waste must be transported with a designated vehicle to an environmentally licensed commercial incinerator.

These increase the cost and effort Georgian farmers must expend. But the market does not value good practice and often punishes the producer for higher production costs. As a result, almost no one follows waste management rules to the letter and the problem of pesticides expands from agricultural plots to other fields. At the same time, farmers deposit pesticide-containing solutions and sprayer residue in the ground, contaminating the farm’s soil, or in irrigation canals and the sewage system. Solid waste, like empty containers, are placed in trash cans or incinerated with other refuse. In the worst case, solid waste is deposited in adjacent plots or in irrigation canals and rivers.

Pesticide Use Regulation in Georgia

Importing pesticides is not subject to the value-added tax (VAT), which keeps their price low and accessible. This also helps stimulate the consumption of pesticides. The diagram below shows the difference between pesticide imports and exports, revealing the quantity of pesticides that stays and is used in Georgia. Over the past two decades, pesticide use has increased almost five times.

Diagram 3: Pesticide Use in Georgia 2006-2022 (based on the comparison of imports and exports; data from GeoStat)

The current legislative framework regulating the use of pesticides in Georgia dates to the adoption, in 2012, of Food Products/Animal Feed Safety, Veterinary and Plant Protection Code.[16] The adoption of this code is related to the signing of the Association Agreement between Georgia and the European Union, which includes a commitment to introduce European approach and principles on food safety and to develop mechanisms of state oversight. The Law of Georgia On Pesticides and Agrochemicals, adopted in 1998, predates the food safety code and, despite numerous changes, remains in force.[17] It continues to define the legal basis for regulating the efficient and safe use of pesticides and agrochemicals.

According to the Association Agreement Implementation Report prepared in 2021, only 20% of commitments related to food safety and veterinary and plant protection have been fulfilled, despite the fact that we are already halfway through the planned timeline.[18] One reason for this lag is the fact that the legislative harmonisation encoded in the agreement specifies the timeline of adoption of legislative changes, but not of their entry into force. As a result, an established practice has emerged, in which Georgia adopts normative acts, but their enforcement only begins years later.[19]

One good example of this practice is the technical regulation regarding the Maximum Level of Pesticide Residues in Food(s) of Plant and Animal Origin/Animal Feed(s), which was adopted on December 29, 2016 and was planned to enter into force on January 1, 2020.[20] However, as of this writing (December, 2023) the technical regulation is still not in force and it is unclear when it will be so. One reason behind this is that no laboratory in Georgia can determine the level of pesticide residue for more than 70 active compounds,[21] while more than 500 such compounds are currently registered and in use in Georgia.

The responsibility to regulate the use of pesticides is distributed among multiple state institutions. The National Food Agency, a legal entity of public law under the Ministry of Environment and Agriculture, undertakes state monitoring functions within the Georgian territory, while cross-border flows fall under the jurisdiction of the Revenue Service, a legal entity of public law under the Ministry of finance. The State Sub-Agency of Environmental Supervision is tasked with identifying, preventing and addressing environmental pollution. The Labour Inspection Service, under the Ministry of Health, Labour and Social Affairs, oversees compliance with the Labour Code, including on farms and in relation to the use of hazardous agrochemicals. The National Center for Disease Control (NCDC), under the same Ministry of Health, Labour and Social Affairs, is responsible for studying and monitoring health risks (determinants), issuing recommendations for preventive measures, monitoring and analysing population health and keeping medical records, as well as developing methodology for collecting and analysing health-related statistics. The NCDC is also responsible for publishing statistics on food poisoning, which is directly related to food safety.

Because fruits and vegetables are considered, in Georgia, low-risk products, the National Food Agency only collects and analyses samples in markets and grocery stores; furthermore, these checks are irregular and pesticide residue assessment is based on a limited spectrum of compounds. To prevent the marketisation of low-quality agrochemicals, the National Food Agency inspects specialised stores. In 2022, it fined 20 stores selling pesticides and the fines were either 500 GEL or 1000 GEL. The violations identified mostly concerned the packaging, storage, and labelling of pesticides, as well as instances of unregistered or unrecognised commerce. Up to 600 registered vendors are currently selling pesticides and agrochemicals and the government plans to inspect all of them. Inspection of agricultural enterprises, especially of smaller and medium-scale farms, is almost non-existent. Likewise, nobody inspects imported agricultural products.

Diagram 4: Probable Cases of Food Poisoning in Georgia[22]

As for the monitoring practices related to food safety,[23] 45 samples of fruits and vegetables were collected in 2003 and none displayed any pesticide residue. Such a positive result is likely a consequence of the limited laboratory capacity discussed above.

Deficiencies of the monitoring system are exacerbated by the fact that waste storage and treatment facilities are extremely limited and inaccessible to farmers. Treatment facilities and technology are especially lacking for expired and especially hazardous pesticides. As a result, as part of several international projects, Georgia exported its expired pesticides for treatment abroad.[24] These problems must be addressed in the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) component of the Waste management Code. The norm should have been introduced in December 2019, but it is still not in force.

Sustainable Pesticide Management: First Steps

The Ordinance of the Government of Georgia On Measures to Achieve Sustainable Pesticide Management, issued in 2021, entered into force on January 1, 2024 as part of the Food Safety Code.[25] The ordinance defines the legal framework of sustainable pesticide management, which aims to reduce the risks and impact associated with pesticide use, including through integrated pest management practices and such alternative approaches and methods as organic pesticide alternatives. The practices that such measures must be based on, ensuring compliance with regulations, will be published by the Georgian National Agency for Standards and Metrology.

It is important to note that the ordinance introduces requirements for both the sellers and buyers of pesticides. To put it simply, distributors of agrochemical products, as well as the personnel behind the counter at agricultural stores, are now required to be specially trained and hold a corresponding certificate. Consumers, too, have new responsibilities. This approach presupposes the existence of substantial knowledge, capacity and infrastructure, which is not currently accessible. Therefore, ensuring compliance with new requirements is likely to be complicated, necessitating the empowerment of public and private stakeholders involved.

Recommendations

Some of the major challenges related to pesticide management include the sector’s informal nature, heavy dependence on imported grains, fruits and vegetables (which, like domestically produced fruits and vegetables, are not monitored for safety), limited purchasing power of domestic consumers, a low level of competence and awareness among farmers and farm personnel, regulatory gaps, inadequacies in legislative frameworks and their enforcement mechanisms, a limited quality infrastructure (like limited laboratory capacity) and insufficient investment in research and development within the fields of medicine and education, including extension services.

Close coordination among state and private actors, as well as civil society stakeholders and educational organisations is a necessary precondition for ensuring effective and safe pesticide use. Substantial investment in infrastructure necessary for sustainable pesticide management is another key objective.

Farmers must be able to implement good agricultural practices and satisfy certification requirements. Delivering safe and environmentally friendly products would also allow Georgian farmers to gain access to better markets, like those in the European Union.

[14] “Agricultural extension” is a form of informal education, which includes providing advice and information to farmers to help increase their productivity, competitiveness and qualification.

[21] Pesticide residue is the residue left behind by plant protection solutions, including active compounds, metabolites and/or decomposing agents, as well as by-products of active compounds that remain in/on foods and pose a threat to consumers. Therefore, all pesticide products specify, along with the proper concentration for treating crops, a safe wait time, which is defined as the number of days that must pass between last treatment and harvesting.

[22] The National Center for Disease Control, 2023. https://www.ncdc.ge/#/blog/blog-list/f10b3ffb-da47-4488-94df-2f03764cf365