Tigran Amiryan, founder of the Cultural and Social Narratives Laboratory, reflects on the foreign agent law adopted by the Georgian Parliament earlier this year in a broader regional context. The new law will be a major stumbling block to cooperation between Georgian civil society and its Western partners on the road to European integration and will have a negative impact on the democratic order in the region. Civil society representatives have expressed their concerns and dissent not only in Georgia but also in Armenia.

In the spring of 2024, Georgia’s ruling party again pushed for the adoption of the foreign agent bill, which sparked protests in Tbilisi and other cities. Despite widespread unrest and pushback from civil society, the bill was approved by a majority vote in late May. It is an unprecedented leap backwards in Georgia’s democratization and a major blow to its hopes of EU accession. Foreign critics warn that the new law is incompatible with international human rights standards and suggest increased support for the Georgian opposition and civic initiatives. On the other hand, Georgian human rights organizations see the law as an attempt by the authorities to suppress civil society and create favorable conditions for the ruling party ahead of the upcoming parliamentary elections in October.

“The elections in October are not normal elections – we see it as almost a referendum between Russification and EU-integration. This is the choice for Georgia,” Georgian human rights defender Baia Pataraia says in an interview. This turn toward “Russian-style authoritarianism” has changed the political landscape not only of Georgia but of the entire South Caucasus. Representatives of Armenian civil society organizations, deeply concerned about the changing regional politics, expressed solidarity with their Georgian colleagues who fought against the bill throughout the protest movement in Tbilisi.

The Caucasus Map of Democracy

For many years, Georgia has been the democratic frontrunner in the South Caucasus. Its aspiration to become part of Europe, or at least Eastern Europe was not just an ambition of Georgian civil society but was reflected in clearly articulated action plans. Until 2018, Armenia lagged behind Georgia, whereas Azerbaijan was rapidly slipping towards authoritarianism. Thanks to the proper functioning of democratic institutions and the transformation of the country as a whole, Georgia made significant progress in democratization and moved closer to the EU not only in the South Caucasus but throughout the post-Soviet space. Georgia’s accomplishments didn’t go unnoticed by the neighboring countries. In particular, for Armenian civil society, Georgia was not just a geographical neighbor, but also as an inspiration and facilitator of democratic governance.

Despite Georgia’s success story, the situation in the region has been changing in recent years. The democracy scores of these countries have been transformed, which happened not only because of the political developments in Georgia, but also in Armenia: the Velvet Revolution (2018), the Second Nagorno-Karabakh war (2020), the Azerbaijani offensive in Nagorno-Karabakh (2023), etc. According to polls conducted until 2022, a significant proportion of Armenians still believed in Russia’s support and influence, which contrasted sharply with the sentiments of Georgian society, especially the youth who mostly support the process of rapprochement with the EU. However, the perception of regional security among Armenians changed dramatically after September 2023 when Russian peacekeepers failed to intervene during Azerbaijan’s military offensive and forced deportation of the entire Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh. Over the past year, the general opinion of Russia in Armenia has become increasingly unfavorable: both as an aggressor state that invaded Ukraine, and as incapable of providing security in the South Caucasus. At the same time, Armenia has been deepening its cooperation with the EU in various areas, ranging from economic diversification to strengthening academic and cultural ties, and most importantly, increasing the EU monitoring mission on the Armenian side of the Armenia-Azerbaijan state border. These cardinal changes and their outcomes have demonstrated that Georgia is no longer the only country in the region where its citizens choose the path of democracy. At the same time, for Armenia, due to its isolated position, Georgia’s political stance is extremely important; Armenian society closely follows the developments in Tbilisi. The adoption of the “Russian law,” or the law on “transparency of foreign influence” could not leave indifferent the representatives of Armenian civil society organizations which have close ties with their Georgian colleagues both within the framework of the Eastern Partnership and due to their geographical location.

Voices of Support

Shortly after the first reading of the foreign agent bill in early April, a number of Armenian NGOs voiced their concerns and issued a letter of support to their Georgian colleagues. In their statement, several prominent representatives of Armenian civil society expressed their solidarity with their Georgian partners in their struggle against the bill, which would restrict civil liberties and fundamental human rights — a danger known from recent history to both Armenian and Georgian society. During the mass street protests accompanied by brutal police crackdowns in Tbilisi, Armenian civic activists voiced their support for the protesters in Georgia. Armenian media regularly covered these events. Political analysts shed light on the possible negative consequences both for Georgia and Armenia, which seeks to distance itself from Russian influence. The “Russian Law” became the main topic of discussion at closed-door meetings and several conferences originally planned with a different agenda.

According to Gevorg Ghukasyan, Executive Director of “Restart Gyumri” Civil Youth Centre, “For the past decade, Georgia has been a beacon of democracy in our region. Soon Saakashvili came to power, thousands of students participated in exchange programs, which had a great impact on the formation of a vibrant civil society. Armenia has in many cases based its reforms on Georgian experience adopting their formats. If the Georgian authorities opt for rapprochement with Russia, while we are preoccupied with economic diversification and searching new security partners in the West, it will mean that Armenia will be left alone with its aspirations surrounded by authoritarian regimes.” Gevorg Ghukasyan also points out another sensitive issue that is usually overlooked in many public discussions: “The conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan was most often discussed in Georgia, and meetings and dialogues between civic activists of these two countries were held there. This law will limit the opportunities for dialogue between our societies.”

A Space for Dialogue

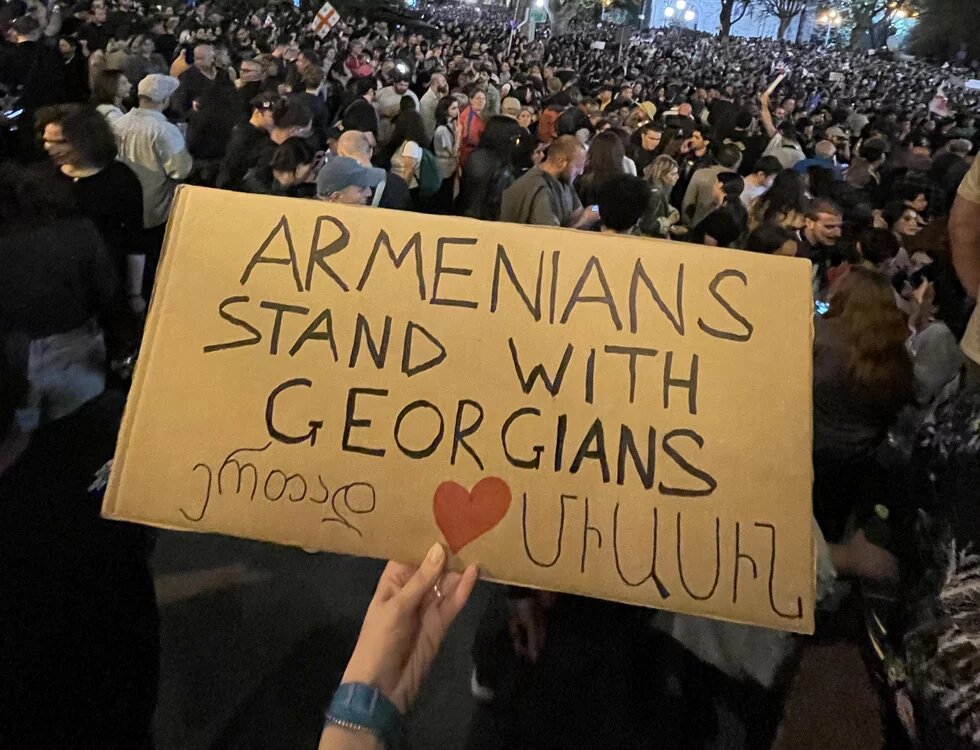

During the almost 30-year history of the post-Soviet conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, a whole generation of people has grown up in both countries who have never interacted with citizens of the opposing sides. Georgia has often become a neutral territory where meetings and dialogue were possible not only for government officials, but also for young activists interested in a peaceful resolution of this conflict. Shortly after the first reading of the foreign agent bill, among the peaceful protesters in the streets of Tbilisi one could spot a placard of a female activist with the slogan “Armenians Stand with Georgians. Together!” A day later another placard held by young protesters on Freedom Square in Tbilisi appeared in the media. This time the inscription read: “Armenians and Azerbaijanis in solidarity with Georgians. This affects us all!” Tbilisi has once again become a place where solidarity between the peoples of the region is possible.

Researcher Mariam Yeghiazaryan, who is actively involved in dialogue projects between Armenia and Georgia, speaks of the importance of Georgia as a neutral meeting place for Armenians and Azerbaijanis: “Apart from the fact that I am now the manager of the annual Georgian-Armenian Dialogue, what connects me to Georgia is that I studied at GIPA (Georgian Institute of Public Affairs). This is a unique chance for young people from Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia to go through the educational process together, to discuss both the consequences of regional conflicts and the ways to resolve them.” Mariam also notes that GIPA is an American initiative that gives young people the opportunity to get a quality education without leaving the region. It is also a space for dialogue. The GIPA program is structured in such a way that from Georgia you go to other European countries to continue the educational process. So Georgia becomes a kind of bridge between Armenia and Europe.” Mariam works at the Cultural and Social Narratives Laboratory (CSN Lab), an organization that for many years has served as a platform for local and regional dialogue between human rights defenders and cultural activists. In mid-April, CSN Lab published another letter in support of its Georgian colleagues, stating that the adoption of the foreign agent bill would be a serious obstacle to cultural cooperation between the two countries and, consequently, to a peaceful atmosphere in the region.

It should also be noted that since 2020 Georgia has become a place of work both for Belarusian activists expelled from their country and for many Russian CSOs banned and forced out by the Kremlin’s “cannibalistic” laws after the invasion of Ukraine. Thus, Georgia gradually acquired the image of a “safe haven” not only for Armenian and Azerbaijani NGOs but also a space for free dialogue for free dialogue and activism of regional significance.

Cooperation vs. isolation

After the final adoption of the foreign agent bill, the EU was forced to move from words to deeds; letters of concern or solidarity, warnings and recommendations by many international organizations were replaced by a political decision to halt Georgia's accession to the bloc. This was followed by anxious anticipation of the upcoming parliamentary elections in October. During this period, both Georgian and Armenian experts are trying to analyze possible scenarios that will develop in the region.

Political scientist Hovhannes Galstyan notes that the reaction of Armenian NGOs was rather weak: “Apparently, we don’t fully realize the grave consequences of the adoption of the foreign agent law in Georgia and the alienation of this country from its aspiration to become part of the EU. It should be said that the reaction of Armenian civil society followed not so much after the reintroduction of the bill but after thousands of protesters took to the streets of Tbilisi. The new law will certainly have a negative impact on Armenia. Georgia’s connection with the EU is our way of dialogue with the bloc and if Georgia finds itself cut off from Europe, we’ll be left without an important mediator along the path of European integration. And even if today the government and civil society try to align more closely with the EU, this cooperation will eventually weaken without Georgia.”

The adoption of this law and the suspension of Georgia’s EU candidate status will not only fundamentally reshape the map of democracies in the South Caucasus, but also the ways in which the EU cooperates with post-Soviet countries. In her commentary, political scientist and orientalist Anna Davtyan-Gevorgyan notes that over the years the Eastern Partnership (EaP) project has become more and more challenging and now the idea of cooperation with Europe in tandem will become even more complicated for these countries: “If you look at all six countries of this partnership, almost none of them are interested in cooperation in this format anymore. Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine were already one step ahead of what this platform could offer recently, Belarus has stopped cooperation — there is interaction only with civil society in exile — and Azerbaijan is interested only in the energy component. It turns out that we are left practically alone on this platform. Anna Davtyan-Gevorgyan also notes that Georgia's new path will reduce Armenia’s room for maneuver, and at some point opposition forces in Armenia may propose to duplicate the foreign agent law.”

Despite the efforts of NGOs and various media platforms, it was difficult for the Armenian public to draw attention to the events in Georgia due to the aggravated political situation in Armenia. As a result of the delimitation of the Armenian-Azerbaijani border in the Tavush region, four villages were ceded to Azerbaijan, which became a trigger for a new opposition movement led by Archbishop Bagrat Galstanyan. At one point, the squares of both capitals were crowded with protesters: while in Tbilisi young people demanded the abolition of the foreign agent law, Galstanyan's movement gathered thousands of people, demanding the resignation of Nikol Pashinyan and chanting “Armenians - Armenia - God - Fatherland.” The latter turned out to be a veiled translation of Russian nationalist slogans such as “For Faith (God), Tsar, and Fatherland” or “Russia for Russians.” Against the backdrop of these protests, parliamentary and extra-parliamentary opposition forces, dissatisfied with the ruling party’s political course, are increasingly advocating the adoption of a foreign agent law along the lines of Russia or Georgia. Justifying the decision of the Georgian authorities, the representative of the parliamentary opposition Lilit Galstyan stated that the law is aimed at strengthening Georgia’s security and should not cause such a reaction from civil organizations.

Thus, the adoption of the foreign agent law in Georgia raises serious concerns in neighboring Armenia for a number of reasons, including Russia’s growing footprint in the region, the obstacles in the way of the the EU-Armenia dialogue, and the isolation Armenia will face due to its peculiar geographical position in the South Caucasus. As experts argue, a beacon of democracy cannot survive for long surrounded by autocratic regimes. While for Georgian civil society, the upcoming parliamentary elections are a new hope for a change of government, Armenia waits for them in the hope of not becoming completely isolated.

The content of the publication is the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Heinrich Boell Foundation Tbilisi Office - South Caucasus Region.