Even though air pollution is responsible for thousands of deaths every year, most people in Georgia are unaware of current air pollution-related policies and remain uninformed about air quality in their residential area.

According to the World Health Organization, nine out of ten people breathe polluted air, which leads, on average, to 7 million air pollution-related fatalities per year. Air pollution is responsible for a third of deaths from stroke, lung cancer and heart disease. Exposure to polluted air is also related to numerous other diseases, including type 2 diabetes, obesity, inflammation, Alzheimer’s disease, and dementia. In Georgia in 2016, air pollution was responsible for 6,845 deaths.

These figures outline the extent of harm air pollution can inflict and underline the importance of understanding its nature and causes, as well as current air quality-related policies and needs in Georgia.

What Is Air Pollution?

According to Georgian law On Ambient Air Protection, “air pollution” covers “any substance emitted into ambient air as a result of human activities, which adversely affects or may adversely affect human health and the natural environment.”

Both natural and anthropogenic sources can emit pollution. Some of the major categories included in the latter are industry, transportation, production of energy, waste, and agriculture. Of these, this article discusses transportation and industry, since most concerns and discussions regarding air pollution in Georgia are focused on these two sectors of the economy.

How to Check the Quality of Air Around Us?

Official data on air quality can be accessed through the air.gov.ge portal. The online portal allows the viewer to continuously monitor live updates on air quality in four cities: Tbilisi, Rustavi, Kutaisi, and Batumi.[1]

Air quality monitoring stations track six major pollutants: particulate matter (PM10 and PM2.5[2]), nitrogen dioxide (NO2),[3] ground-level ozone (O3), sulfur dioxide (SO2), and carbon monoxide (CO). According to the 2020 data, in all four cities only the particulate matter concentration exceeded the norm.

However, apart from automated air quality monitoring stations, information is also gathered at additional points in 25 points, where indicative data is gathered during two-week measurement periods four times a year. These are conducted by installing sampling tubes that are later sent for analysis to an accredited laboratory in the United Kingdom. Results are published on the air quality portal.

In 2020, 12 out of 25 indicative monitoring points in Tbilisi captured concentrations of nitrogen dioxide exceeding the norm. In 8 cases, the concentration exceeded the norm by 50% or more. Results were relatively better in 2021, when nitrogen dioxide concentration exceeded the norm at 9 points out of 25.

Compared to stationary monitoring, regulation regarding the quality of data gathered through indicative measurement is less demanding. For example, the acceptable range of measurement error is as high as 50% for particulate matter and 25% for nitrogen dioxide. Therefore, for a full and precise picture of air quality, the expansion of the automated stationary network is crucial.

When discussing the dearth of automated monitoring stations, it is especially concerning that the mobile air quality monitoring station owned and operated by the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Agriculture was left idle[4] for more than a year and a half in Poti, its capacities unused for data collection.[5]

Unfortunately, the management of data collected is sometimes as much of a problem as gathering sufficient measurements. This problem is not exclusive to environmental governance and is also discernible in other fields, including public health. As a result, there is no framework that would ensure the ability to draw reliable conclusions regarding possible connections between air pollution and the prevalence of disease. Lack of sufficient data curtails the capacity of researchers to conduct such studies, which hinders evidence-based environmental policymaking.

Recent data from various agencies confirms the fact that the inefficient implementation of policies aimed at improving air quality is producing a heavy social burden, affecting not just public health, but also the economy. According to a 2019 report from the Office of the Public Defender (Ombudsman), in 2016 alone, the government had spent 120,050,566 GEL ($59,139,562 USD) to cover medical costs of treating diseases related to air pollutants (NO2, SO2, CO, O3, PM10 and PM2.5). A World Bank report from 2020 further estimates that the medical burden stemming from ambient and indoor air pollution equals $560 million USD, comprising 3% of Georgia’s GDP in 2018.

Safe Levels of Pollution

Available data indicates that chief pollutants exceeding safe concentrations in Georgia’s cities are particulate matter and nitrogen dioxide. Therefore, below we will focus on them. The World Health Organization (WHO) revised and decreased acceptable levels of concentration of these pollutants in September of 2021. The revisions aimed at curbing emissions as much as current capacities allow.

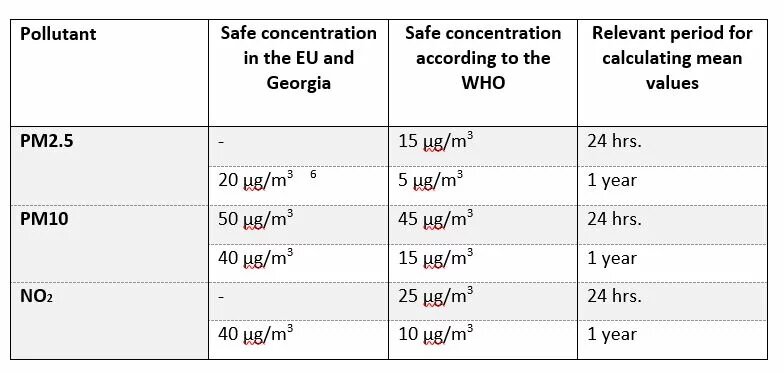

According to revised standards, the safe concentration of PM2.5 is set at 5 μg/m3 (which means that the mean annual concentration should not exceed 5 μg/m3); the safe level of mean annual concentration of PM10 is fixed at 15 μg/m3, while 45 μg/m3 is the new threshold concentration for the daily mean; the safe annual mean concentration of nitrogen dioxide has been decreased from 40 μg/m3 to 10 μg/m3.

EU standards, which set the threshold concentrations in Georgia, are more permissive. The thresholds for the mean annual concentration are 20 μg/m3 for PM2.5 and 40 μg/m3 for PM10; for nitrogen dioxide, the threshold value is 40 μg/m3. The maximum allowable daily mean concentration of PM10 is 50 μg/m3 but it is considered safe only if the threshold is exceeded on 35 days or fewer in a year. Unfortunately, such days are more frequent than this standard allows in Rustavi. According to the 2021 fulfillment report of the “Action Plan to Improve Air Quality in Rustavi (2020-2022)”, the concentration of particulate matter of the smallest size in the air exceeded the norm by 60%.

To better understand threshold values of safe concentrations of major pollutants, the chart below compares regulations from the WHO, EU, and Georgia.

Foundations of Air Quality Regulation in Georgia

Threshold concentrations of harmful pollutants in Georgia correspond to those mandated by the EU, but their enforcement has been a persistent challenge.

The law On Ambient Air Protection was ratified in 1999. It “regulates protection of ambient air from harmful anthropogenic impacts in the territory of Georgia.” It does not cover indoor air quality.

The law specifies, that “the legislation of Georgia in the field of ambient air protection consists of the Constitution of Georgia, treaties and international agreements of Georgia, the law of Georgia on Environmental Protection, the law of Georgia on Health Care, this law and other legal and subordinate normative acts.”

The original, 1999 version of the law On Ambient Air Protection stipulates, under section D of the Main Goals and Tasks of the Law, that one of the goals of this legislation is “to support gradual entry into force, in the territory of Georgia, of legal norms established under EU legislation in the field of protection of ambient air from pollution.”

The passage demonstrates that EU legislation was given special importance from the very beginning of the process. Today, this stipulation is further complemented by commitments included in the 2014 EU-Georgia Association Agreement (AA).

Between 1999 and 2022, 22 edits were introduced in the law On Ambient Air Pollution. The majority of these edits concern administrative matters and reflect institutional changes in the Government of Georgia. But there have also been substantive revisions of the law. Recent changes are mostly related to efforts to harmonize air quality legislation to that of the EU.

Chapter 3 of the EU-Georgia Association Agreement concerns environmental policy. Article 302 of the chapter stipulates that “cooperation shall aim at preserving, protecting, improving and rehabilitating the quality of the environment, protecting human health, sustainable utilisation of natural resources and promoting measures at international level to deal with regional or global environmental problems, including [among other things] in the area of air quality.”

The AA also discusses the importance of supporting the modernization and restructuring of industrial production in ecologically sustainable ways.

Appendix XXVI of the AA lists specific deadlines for fulfilling commitments entailed in the document, including for the five directives under the section on air quality.[7] Directive 2008/50/EC includes, among other commitments, an obligation to establish and classify “zones and agglomerations” and to prepare air quality plans for those zones and agglomerations where pollution levels exceed limit/target values (Article 23); preparation of short-term action plans for those zones and agglomerations where “there is a risk that the levels of pollutants will exceed one or more of the alert thresholds” (Article 24). Consequently, the law On Ambient Air Protection was revised on May 22, 2020 and the territory of Georgia was divided, for air quality preservation and improvement purposes, into zones and agglomerations. Plans for addressing air quality is to be prepared based on this demarcation. Similar plans have previously been prepared for Tbilisi and Rustavi, but the fulfillment of both was marred by multiple problems.

For example, according to a fulfillment report on the 2017 program “Supporting Measures to Reduce Ambient Air Pollution in Tbilisi”, 45% of measures had not been carried out. These included key interventions, timely implementation of which would have helped, among other things, decrease pollution from the transportation sector.

In the case of the “Action Plan to Improve Ambient Air Quality in Rustavi” ratified in 2020, implementation deadlines are often missed, especially for legislative changes.

Apart from these issues, the AA also discusses air quality in the chapter on industrial pollution and hazards and includes obligations that are to be fulfilled within 12 years of the document’s coming into force. These include the commitment to deploy “best available technology” and to prepare national transitional plans to reduce total annual emissions from the industrial sector.

Fourth National Environmental Action Programme of Georgia (NEAP 4) acknowledges the problem that there is no unified, comprehensive legislative framework that would regulate industrial production and address all hazards characteristic of the sector. However, through the AA, Georgia has committed to an obligation to gradually make its laws and regulations in the field of “industrial pollution and hazards” compliant with that of the EU. More specifically, Georgia is to harmonize its national legislation according to the obligatory articles of the directive on Industrial Emissions. This would also include the introduction of an integrated licensing system and measures to deploy best available technology.

The website of Georgia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs publishes fulfilment reports on the action plans related to the agenda of the AA, allowing us to access information on those related to air quality as well.

These reports further demonstrate that most measures aimed at improving air quality are related to the AA. These include legislative changes, introduction of corresponding decrees and technical regulation, expansion and automation of the air quality monitoring network, delivery of timely and comprehensive information on air quality to the public, creation of the air.gov.ge portal, the establishment of air quality management zones and agglomerations, preparation of action plans aimed at improving air quality and more.

Air Quality Legislation – Main Challenges in Environmental Oversight of the Industry

Over the past few years, laws regulating air pollution from industrial sources have improved.

Revisions to the law On Ambient Air Pollution passed by the Parliament on March 2, 2021, made it mandatory for some industrial factories to automatically monitor and report emissions of any harmful waste. Despite this, Rustavi’s example shows that the law contains numerous loopholes in terms of enforcement mechanisms. A year and a half after the ratification of the revisions, only 4 out of 25 factories comply with new regulations. Other environmental regulations have faced similar enforcement challenges.

Another problem that demonstrates insufficient enforcement is that some industrial factories required by law to install air filtration systems at the start of operations have still not met this requirement. Some factories have been in breach of this regulation for more than ten years.

Another important challenge concerns factory inspections. Apart from being infrequent, most inspections are insufficiently thorough and planned in advance. It would be desirable to increase the number of unplanned inspections carried out without prior notification. Industrial plants are usually able to prepare for planned inspections, allowing them the opportunity to present a better picture than their normal, everyday operations would paint. For example, if they have installed filters but do not use them every day, they might make sure to turn them on specifically for inspection.

Inadequate inspections are also related to the fact that factories often do not comply with terms and conditions specified in the environmental decision and in the environmental impact assessment (EIA). Consequently, factory performance might look good on paper, but be very different in reality.

Additionally, according to NEAP 4, efficient regulation of industrial emissions, which is a consequence of not having an integrated licensing system, is a major challenge for Georgia.

The existing licensing procedures do not involve the obligation to deploy best available technology (BAT), do not set corresponding and specific threshold values for emissions from stationary sources and issue environmental decisions that never expire. Therefore, for effective environmental oversight of the industrial sector, creating a flexible and regularly updated licensing procedures that would address actual conditions in the factory is of crucial importance.

When it comes to oversight, another problem stems from the fact that there are no digital instruments supporting compliance with legal requirements. Such instruments could provide a medium for monitoring compliance with regulations, track implementation timeline in a systematic way (through, among other things, an online database of environmental assessments), provide businesses with compliance reminders and simplify procedures for relevant agencies.

For example, for six months, the Gavigudet (We Are Suffocating) movement demanded the formulation of a schedule indicating when each factory would install air filtration and continuous, automatic monitoring systems. Circumstances pointed to the fact that the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Agriculture began putting such schedule together only after Gavigudet planned protests. This is a further demonstration of current failures in environmental oversight.

To sum up, regulating emissions from stationary sources remains riddled with problems. Apart from a lack of political will, dearth of human resources, competence, and resources, as well as legal loopholes might also be contributing factors. Therefore, it is necessary to strengthen institutional capacity in the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Agriculture, support training of key personnel and help share relevant experience from the EU.

Transportation and Air Pollution: An Overview

Besides industry, transportation – and automobiles in particular – is a major contributor to air pollution.

Cars are responsible for 43% of nitrogen oxide emissions. Insufficiently developed public transportation helps increase emissions from the transportation sector. Both inter-city and intra-city routes remain problematic. Consequently, even people who would rely on public transportation if they could, have to purchase private cars. Due to economic difficulties, most people are unable to afford new vehicles – 83% of registered cars (1.47 million) are 10 years or older; 23% are more than 30 years old. Older vehicles are more polluting.

Public transportation must be developed further, while sidewalks and bike lanes must be improved – these would help decrease demand for private vehicles, especially in light of the fact that automobiles account for 85% of all vehicles on the road.

What’s more, despite the fact that technical inspection requirement was reinstated for automobiles in 2018, effective functioning of this mechanism has become a challenge.

In an interview he gave us, Noe Megrelisvhili, the Head of Ambient Air Division at the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Agriculture, noted that some car owners pass technical inspection with rented parts, which they return after successful completion of the tests. Legislative changes have been initiated to address this issue. Cars in need of maintenance will incur higher fines, while the Department of Environmental Supervision will begin testing exhaust on the road. To achieve this, the Department of Environmental Supervision will acquire a vehicle and instruments detecting and measuring carbon monoxide, as well as soot, and will begin with patrolling in the major cities. These measures have already been included in the budget for 2023 and negotiations are underway with potential donors to finance the purchase of the vehicle and the instruments.

Apart from the poor state of vehicles, air pollution from automobiles is also related to the quality of fuel. A number of steps have been taken to improve fuel quality controls and relevant laws have been made more restrictive. It is now against the law to import, domestically produce or consume fuel that does not comply with standards. Permissible levels of lead, benzol, arenes and sulfur concentration in gasoline have been gradually lowered. Acceptable concentration of sulfur in diesel has also been decreased. Beginning in 2023, concentration of sulfur in diesel must not exceed 10 mg/kg – a dramatic reduction from 350 mg/kg allowed in 2010. Noe Megrelishvili indicated that the enforcement of this revision was delayed multiple times, since one of the major importers of diesel was unable to adjust its operations and provide fuel of this quality. However, regulation can now be complied with, and its enforcement will not be delayed any further.

Another problem relates to smaller gas stations, where inspection has detected excess sulfur in diesel. Specialists at the ministry think that these incidents are due to local processing and solvents. A special inquiry will address this issue to determine the cause and sources of excess sulfur in diesel. If solvents are discovered, appropriate fines will be applied. These incidents form only a small portion of total fuel consumption and most of it will comply with standards.

Noe Megrelishvili points out that raising fines for selling sub-standard fuel at gas stations has been another important development. Previously, the fine amounted to 8,000 GEL ($3,000 USD). The amount has now been increased to 20,000 GEL ($7,500 USD). Additionally, the penalty now includes an extra fine based on the amount of product prepared for selling – so apart from the fixed fine, non-compliant gas stations have to pay five times the market price of all fuel in their reserve tanks.

Some of the measures directed at improving the quality of fuel have been effective and, according to the online air quality portal, gasoline tests conducted across different sectors in different laboratories have all confirmed that no gasoline currently on the market contains lead. Improvements in fuel quality have led to a significant decrease in the airborne concentration of pollutants like sulfur dioxide, benzol and arenes. Sulfur dioxide concentration is well below the acceptable level throughout the country, while cases of benzol concentration exceeding the norm are practically nonexistent.

Indeed, in May 2020, the Department of Environmental Supervision collected 252 samples of gasoline from 251 gas stations across the country, testing them for lead and sulfur content. Lab results have shown that the concentration of both lead and sulfur were below the norm in all samples, while the octane value was flagged for just a single sample.

Despite these improvements, some challenges remain. In April 2020, the Department of Environmental Supervision collected 43 samples of diesel and 49 samples of gasoline from 29 gas stations across the country.

Diesel samples were tested for cetane value, density, and sulfur content. 14 out of 49 samples had excess sulfur; one sample was sub-standard for its density, as well as sulfur content.

Gasoline samples were tested for octane value, lead and sulfur content. 18 out of 49 samples were shown to have octane values below that mandated by the decree of the Government of Georgia.

According to Noe Megrelishvili, financial constraints present another problem, affecting the capacity to conduct inspections with the frequency mandated by EU standards. Inspection of gasoline and diesel products now includes testing for additional components (new technical measurements like steam pressure, ignition temperature and water content), making quality tests significantly more expensive.

***

As this article demonstrates, the issue of air pollution is complex and multi-layered. Due to the limitations of this form, we have not been able to cover numerous important topics, like natural sources of air pollution, indoor air quality, agricultural sources, emissions from the energy sector, waste management and more. We have also not been able to discuss how air pollution affects workers’ rights.

It is important to take timely action to address each of these issues. If political will to do so will be lacking, citizens must make sure that air pollution remains on the political agenda.

This has been the driving mission of Gavigudet for 5 years. Progress has been slow, but noticeable – representatives of the ministry and of factories in Rustavi agree that the advocacy efforts of the locals have ensured that more attention is now being paid to air pollution than ever before.

For faster progress, more people should get involved and they should be included in the decision-making process, this would help generate and sustain political will inside the government to solve this urgent problem.

The content of the publication is the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Heinrich Boell Foundation Tbilisi Office - South Caucasus Region

[1] For brief instructions on accessing data from the monitoring stations, you can see a short video concerning the example of Rustavi.

[2] Of these four cities, particulate matter concentrations are most concerning for Rustavi. Additionally, PM affects more people than any other pollutant. Excessive concentration of PM can cause asthma, bronchitis, lung damage, cancer, poisoning with heavy metals, irriation of the eyes, and adverse impact on the cardiovascular system. Exposure to high PM concentrations can also affect cognitive function and mental health outcomes.

[3] Exhaust from automobile engines is the primary source of nitrogen dioxide emissions. Exposure to high NO2 concentration increases susceptibility to respiratory infections, irritation of the airways and respiratory symptoms (coughing, chest pain, trouble breathing, etc.).

[4] According to Poti’s Residents for Their Rights, the station near a port terminal only gathered data for five months. In this period, concentrations of PM10 and PM2.5 exceeded the norm on 52 days. But the National Environmental Agency turned off the station for maintenance purpose. Residents in the area distrusted the Agency and did not let its representatives to take the station away.

[5] In October, 2022, the National Environmental Agency transported the station for maintenance and promised locals that it would be returned thereafter.

[6] According to the Directive 2008/50/EC (Appendix XIV) and Ordinance 383 of the Government of Georgia („Technical Regulation – On the Ratification of Ambient Air Quality Standards”), starting from January 1, 2020, the acceptable annual mean concentration of PM2.5 should not exceed 20 μg/m3.

[7] Directives 2004/107/EC, 1999/32/EC, 94/63/EC, 2004/42/EC and Directive 2008/50/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 May 2008 on ambient air quality and cleaner air for Europe.