Although Tbilisi officially aims to become a "Green City," the reality on the ground tells a different story. There is limited access to functional green spaces, rapid urban sprawl and a tendency to prioritize aesthetics over ecological considerations. This article critically explores how governance, design and environmental policies intersect to influence the city's sustainability efforts.

Introduction

Although Tbilisi has seen a noticeable increase in new plantings, the city still faces a significant shortage of green spaces. Recent estimates indicate access to only 1.3 m² of green space per capita, a figure well below the often-recommended minimum of 9 m² and European averages. Although Article 29 of the Constitution of Georgia guarantees environmental protection and the efficient and sustainable use of natural resources, the reality in Tbilisi differs markedly. While some public initiatives yield ecologically grounded projects, most developers and city planners prioritize visual appeal and ease of maintenance over ecological functionality and resident well-being. Despite a significant rise in new plantings throughout Tbilisi, particularly in central districts where the streets now look greener and more modern than they did ten years ago, the city still struggles with a critical lack of genuine green spaces.

As landscape architect Sarah Cowles mentioned in a recent online interview with us, poorly designed or purely ornamental “green” projects can worsen urban crises instead of alleviating them. The lack of proper drainage, shade and biodiversity contributes to severe flooding, extreme heat and declining air quality - issues that Tbilisi is already experiencing acutely (see photos 1, 2 and 3 below). Green projects often involve the planting of expensive, non-native trees chosen for their aesthetic appeal while native species that provide shade and ecological benefits are often overlooked. All of this reflects how short-term economic considerations outweigh long-term sustainability goals.

Rhetoric Versus Reality

Politicians and developers - the real authors of urban change - know that “green” is an effective marketing tool, even when it amounts to little more than a half-truth. What limited greenery they add to their projects does not offset the damaging environmental effects of reinforced concrete construction (the material used in virtually all projects in Tbilisi), increased traffic and flawed implementation.

On paper, Tbilisi is committed to being a “Green City.” Specifically, the General Land Use Plan outlines four main objectives for the city, stating that it should be compact, green, well-connected and resilient. The ‘green’ objective mandates green space ratios, supports the development of recreational spaces and envisions green buffer zones to manage the city’s growth while ensuring residents have access to natural spaces within walking distance. All this is ecologically grounded. In practice, however, the municipality routinely undermines these commitments.

When projects conflict with the Land Use Plan, developers apply for permits to amend it. After a months-long process, the municipality typically grants the permit, adjusting zoning regulations accordingly. A second permit then authorizes construction. In practice, almost no large-scale development project is blocked, leaving the General Land Use Plan largely ineffective.

This happens in cases of both intensive and expansive development: either the municipality increases the maximum allowed building volume by changing an existing residential zone (intensive development) or it changes an area where construction is prohibited into one where it is allowed, expanding the boundaries of the built urban area (expansive development/urban sprawl). The latter is far more problematic for several - perhaps counterintuitive - reasons.

Two Types of Development

More often, critics focus on the adverse effects of intensification. A common objection to densification is that downtown areas already suffer from heavy traffic. However, this argument is inverted: the center is walkable and the suburbs are almost always car-dependent. Since those who live in suburbs still have to reach the center, this results in significantly more motor traffic and, by extension, increased pollution. Furthermore, sprawl requires extensive infrastructure: more streets, pipes and lighting. In Tbilisi, this type of development has become increasingly prevalent in recent years. A comparison of satellite imagery from different years reveals how previously recreational areas were gradually eroded by low-density suburban development. Below are two satellite images of Didi Dighomi: the first is from 2005 and the second is from 2024.

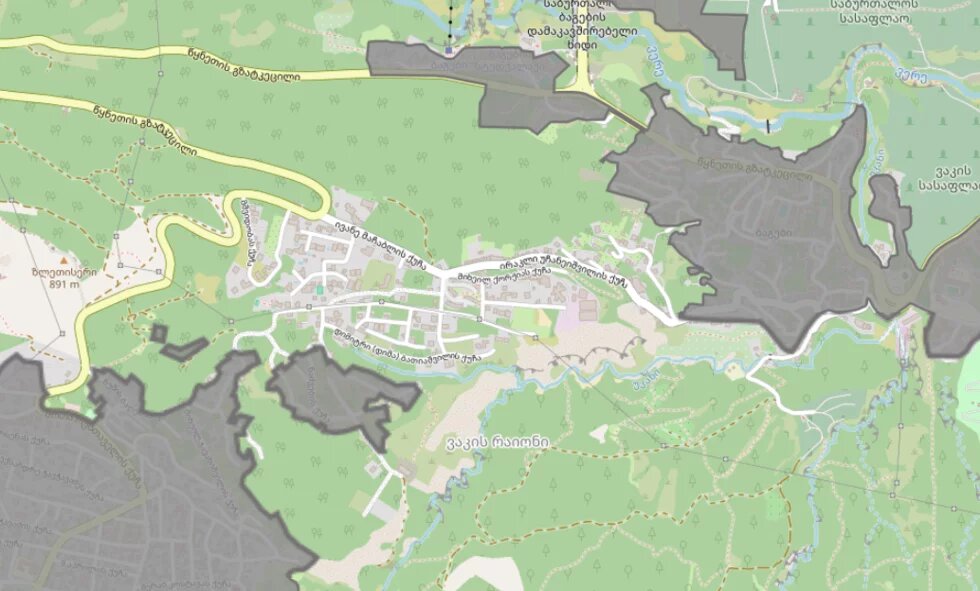

This example is not the most drastic, as in the cases of Kaklebi (image 1) and the area east of Lisi Lake (image 2), suburban developments extend directly beyond the allowed construction area (development contour) outlined in the General Land Use Plan. In the maps below, you can see the “development contour” in gray.

These types of developments also generate traffic, rely on unsustainable materials and impose infrastructure costs. Yet, perhaps the most immediately visible ecological consequence - and the one we should now turn to - is the loss of greenery.

Functions of Greenery

Green spaces provide aesthetic and recreational value but their ecological functions are equally - if not more - critical. They regulate temperature, mitigate floods, reduce noise pollution and improve road safety. Since streets comprise around 80% of urban public space, their design makes a significant difference.

As cities develop, vegetation is replaced with concrete and asphalt. These materials absorb the sun's heat and then radiate it back into the atmosphere. This leads to the urban heat island effect whereby cities are significantly hotter than their surrounding areas. Trees combat this by providing shade and preventing surfaces from heating up, resulting in air temperature differences of up to 4 degrees Celsius and road surface temperature differences of up to 15 degrees. Since virtually all streets - and even most sidewalks - in Tbilisi are made with impermeable, dark asphalt, the shade provided by trees is necessary to mitigate heat island effects. This requires trees with large canopies, not merely decorative species. As Sarah Cowles said during our interview, shade should be prioritized over shape.

Since asphalt and concrete are impermeable, they also create problems in terms of drainage: the higher the ratio of impermeable surfaces, the smaller the areas where rainfall can go. This can have dire consequences in cases of flooding. The drainage pipes in Tbilisi cannot handle the increased water volumes which is why we get mini-floods on almost every rainy day. This is especially problematic around the Mtkvari River. Surrounded by impermeable motorways on both sides, there is no way for rainfall to drain into the river besides overburdened drainage pipes. In Tbilisi, the drainage function of urban greenery is often compromised in implementation: spaces for greenery on streets and parks are typically elevated slightly above the ground and bordered with thin metal sheets, preventing surrounding water from draining naturally into the earth.

When planned well, green spaces can even improve road safety. When a driver perceives a space as narrow, they will slow down. Making spaces seem narrower is where trees can help, even without actually narrowing anything down: studies show that increasing visual complexity through canopied, dispersed trees can make drivers slow down. In contrast, a continuous barrier (like a concrete wall or hedge) can have the opposite effect. In Tbilisi, however, street design and greenery are handled by different departments of the City Hall with little to no coordination, resulting in public spaces that contradict each other.

Another significant problem in terms of implementation is biodiversity. In our interview, Sarah Cowles explained that since there is no local market for native species, most newly planted greenery is imported from Turkey or Italy and these species struggle in a non-native climate. Here, too, procurement decisions are rarely made in consultation with environmental experts. As with infrastructure or construction materials, economic considerations usually outweigh ecological ones, leading to choices driven by cost rather than sound environmental policy.

Conclusion

Weak enforcement of the General Land Use Plan has reduced greenery to an aesthetic afterthought. The municipality’s routine approval of zoning amendments, poor coordination between departments and lack of consideration for sustainability result in self-defeating designs.

The existence of international experience and local expertise suggests that alternative models are both possible and necessary. Initiatives such as the Tbilisi Urban Forest project and internationally supported green infrastructure programs show that ecological functionality can be integrated into urban design. They emphasize biodiversity, storm water management and climate resilience.

What is missing is enforcement. Bridging the gap between rhetoric and implementation requires three main changes: blocking unreasonable amendments to the General Land Use Plan, mandating coordination between City Hall departments and giving ecological function equal priority to aesthetics.

The Content of the article is the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Heinrich Boell Foundation Tbilisi Office - South Caucasus Region