Environmental protection and climate change have never been a top concern for any elections in Georgia while the political establishment has been not-so-Green. The 2024 elections not only seem to be continuing this tradition but show even more neglect for these topics, as the campaign is centred on Democracy vs autocracy and Europe vs Russia. However, the outcome of the elections is not inconsequential for the future of environmental and climate protection as Georgia’s legislative progress has largely depended on EU accession while practical efforts relied on activism; both could be accelerated or halted. Therefore, even if not clearly visible, on the 26th of October, environment and climate are on the ballot

Environmental protection and climate change have never been a top concern for any elections in Georgia. Even municipal elections usually lack genuine conversation about green issues such as mobility and public transport, parks, and recreational spaces. However, this lack of policy focus goes beyond environmental matters. Georgia’s politics is rather a personality contest where there are “good guys” and “bad guys” while policy is not a relevant variable.

2024 elections not only seem to be a continuation but a worsening of this tradition, as parties focus on strictly geopolitical, and only such heavyweight issues as unemployment and economic hardships. Will Georgia remain flawed but still a democracy and continue the path towards Europe or cement autocratic rule of the current government and transform into an isolated regime? Indeed, given the historic character of this parliamentary election which could decide the fate of this country for decades to come, this is understandable. Nevertheless, I would argue that these elections will largely determine the future of environmental protection too. There are two main reasons why: first only in liberal democracy, even if not perfect, the interest groups have a chance to mobilize and have space, tools, and freedom to advocate for their concerns; Second, positions of Georgia’s political establishment offer little hope regarding most of the issues, and especially climate and environment. Moreover, nearly, if not all, legislation concerning climate and environment has been passed through the framework of EU accession as required under the Georgia-EU association agreement. Therefore, though still insufficient as there is a significant gap between the legislation and its implementation—the only progress we have in this regard is largely due to reforms linked with integration with the EU[1]. The latter is already seriously damaged and is likely to be completely halted in the case of Georgian Dream’s victory in October[2].

In addition, for the upcoming October elections, the manifestos of major[3] opposition parties seem to be truly secondary due to the agreement they had signed. This is the “Georgian Charter” which was initiated by President Zourabichvili. The charter outlines an action plan for the coalition government, should they get enough seats after the elections. The action plan is solely focused on bringing back Georgia on the EU integration track and implementing all recommendations and necessary institutional reforms. Primarily directed towards restoring the independence of the judiciary, releasing political prisoners arrested during protests against the so-called “Russian” foreign influence law, depoliticising key institutions such as the Ministry of Interior Affairs and Anti-Corruption Bureau, as well as introducing fairer rules for elections and guaranteeing the neutrality of Central Electoral Commission. The charter outlines that the coalition government, made up of opposition parties, will be composed of non-partisan professionals led by the PM fulfilling those criteria. The mandate will be solely focused on implementing reforms and will be dissolved in a year, allowing free and fair elections in October 2025[4]. Considering that all major opposition parties have signed the charter, their policies thus, we can assume, are less relevant since, as suggested by the Charter, they will not be implemented for this mandate. This argument was explicitly put forward by one of the leaders of the Coalition for Change, which did not release a comprehensive electoral programme, stating that the priority is ousting the Georgian Dream, for which only the Charter matters[5]. However, some politicians and parties have already raised questions regarding certain aspects of the document, particularly concerning early elections[6]. Consequently, since, on the one hand, it is not so certain that Georgia will face early elections, and the 2024 parliament will not be a policy-shaping institution; on the other hand, given that these parties will likely run in the forthcoming elections, potentially with the same platforms, it remains valuable to examine their positions on environmental and climate protection.

Not-so-Green political landscape

The irony of Georgian politics where environmental protection and climate change never managed to galvanize voters or get enough attention from decision-makers, is that the liberation movement seeking independence from the Soviet Union found its birth in the protest movement against environmental degradation, namely the construction of Khudoni Hydroelectric Power Plant (HPP) and Transcaucasian Pass Railway[7]. In the early days of Georgia’s independence, Green party, as the name would suggest, a pioneer of environmentalism in politics, played a role but soon fell into political irrelevance to never come back. During the past three decades, especially since late 2010s, we have witnessed numerous environmental movements of different scale and popularity, some of which dominated the national media landscape for days, even weeks, and months, such as the quite recent Save Rioni Valley protest mobilised to stop construction of Namakhvani HPP. However, the issues of these movements never managed to materialise into political discourse and were either largely ignored by the political establishment or criticised as a “destructive” force[8] harming Georgia’s economy, which, according to their view, is more important than protecting the environment. It is important to note that Georgia’s political establishment rarely takes interest in ongoing environmental movements, outside of times they seriously challenge commercial interests. Again, this lack of interest is not unique to environmental issues; rather, it reflects a broader trend where Georgian political parties generally show limited involvement with different social issues and movements. For instance, currently, there are several active social issues and movements in the country: the labour strike at Evolution Gaming, the anti-mining protest in Shukurti, and the expropriation of a national park waterway in Balda Canyon. All of them are either fully ignored by all parties or their support does not go further than one or two statements on Facebook. Consequently, even when politicians decide to get involved, their actions are perceived not as genuine but rather as opportunistic moves to attract voters and get media attention. In other words, they capitalise on ongoing issues without offering meaningful paths to resolve them.

Going back to the prospects of environmental protection after the elections, considering the recent protests and the dynamics of the green movement with the state actors, it should become clear why and how the October elections will decide the fate of “nature” as well. Since the 2012 elections, which changed the party-in-power, the space for civic activism has opened up, resulting in numerous social and green groups mobilising for a cause. It is worth noting that in many instances, local population or activist groups received support from well-established NGOs, mainly in the form of expertise and analytical input. What was the response by the government (local or national) to these protests or advocacy campaigns? Rather simple: opposition. Let’s take the example of one the largest movements of this kind – Save Rioni Valley. As usual, the ruling Georgian Dream was outspoken against the movement, initiating a disinformation campaign[9], targeting its leaders as unmodern i.e. being against development and thus being Russia’s assets. We must highlight that the opposition parties were, at best scenario lukewarm towards the protest while some openly argued against the movement and advocated the construction of the HPP[10]. The public campaign was accompanied, as per tradition, by intimidation by state security services and demonstrations of force[11]. The movement succeeded, and the planned construction was halted as the Georgian Dream realised it lost the narrative on the issue, the project became too damaging, even among its electorate. However, this success will most likely be temporary and, if the current government maintains power, construction of Namakhvani HPP will be re-initiated[12]. The Georgian Dream never fully backs; instead, it takes a step back only to advance two steps forward. This was evident in the withdrawal of the "Russian" foreign influence law in 2023, which was reintroduced a year later and ultimately adopted after a more carefully planned and managed response.

To have an even better understanding of the current state of play between democracy and environmental protection it would be more accurate to look at the movement organised to stop the privatisation of Balda, a beautiful canyon and a waterfall in Samegrelo region. Unlike the Rioni Valley Movement, Balda did not manage to rump up media attention or gather support outside the region. At the same time, the GD government, which has grown more aggressive since 2022, has dealt with protesters brutally, not shying away from orchestrated violence and even arrest of one of the leaders with trumped up charges[13]. This very well shows the trajectory of GD rule that previously tried to deal with movements by disinformation campaigns and limited use of force. Now the “dark side” has come to light and arrests and violence have become the new normal. Furthermore, the attempts to discredit and silence NGOs will become more intensive after the elections. This will significantly weaken future environmental and social movements, as they will lack the strong professional and expert support needed to complement activist campaigning with legal strategies.

Concurrently to shrinking space for environmental activists to initiate protest or advocacy campaigns, the government is likely to diminish environmental regulations to accommodate local oligarchs or bigger capital in order to keep loyal and/or generate economic growth, or at least a simulation of the latter. For Georgia’s political elite, there is a conflict between environmental protection and economic growth. In the context where movements and NGOs do not have sway over politicians and green issues do not have high priority in voters’ agenda, EU integration remains the main - and usually only - hope. While there is considerable criticism of the new environmental regulations within the EU and a perceived lack of practical tools to accelerate the green transition, in the case of Georgia, it is primarily the EU Association Agreement that holds the potential to introduce progressive legal and policy frameworks for environmental and climate protection.

Where are environmental and climate change issues on the voters’ agenda?

As mentioned above, environmental protection and climate change are not the most pressing issues for the Georgian electorate. It has never been, and it is even less likely to be in the 2024 elections. However, it is not as unimportant in voter’s minds as we might intuitively think. The data published by CRRC earlier this year[14] clearly indicates that people are worried about their environment, and climate change is seen as an important issue (Figure 1). Georgia has seen numerous devastating natural catastrophes[15] in recent years, which were largely exacerbated by the climate crisis. This is something that voters also resonate and are concerned with.

In this context, voters also agree that the state must do more to tackle climate change. The majority of them are even ready to pay higher taxes for that purpose (48%). When it comes to policies, Georgian voters also seem rather open-minded, state subsidies have 90% support while such a controversial issue as banning the sale of gasoline and natural gas cars by 2030 is supported only by 44%. However, I believe this must be taken with a pinch of salt since environmental issues have not been politicised but rather treated as the domain of technocratic solutions. Once it gets into the political mainstream, it is more likely for some policies to get more controversial and climate becomes a polarising issue, instrumentalized by some political parties through the lens of economic growth vs environment. However, despite voters’ willingness to act more on climate change, parties have always neglected this issue.

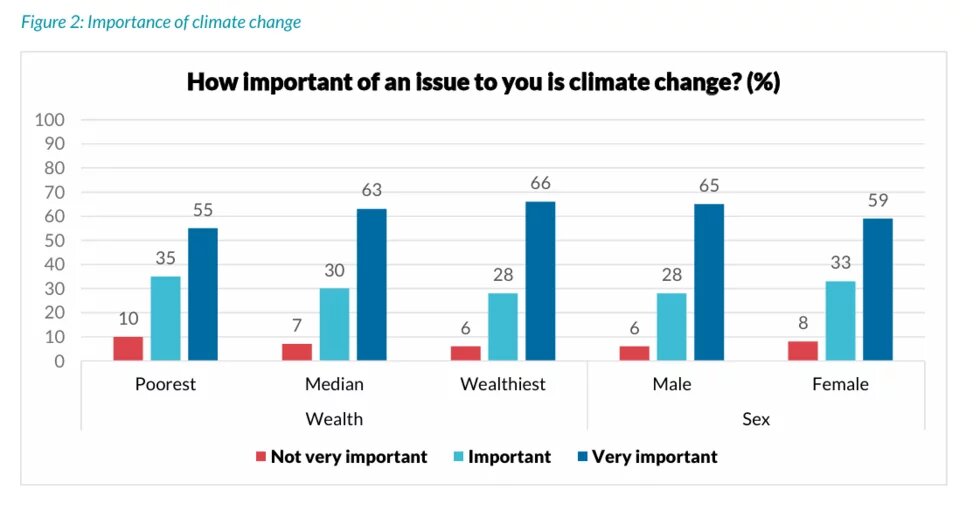

Moreover, in Georgia’s political context, electoral platforms or manifestos have never been a focus of election campaigns. If we closely examine the positions of major parties, we will see clear incoherence and flip-flopping positions over time. In addition, when voters are asked what influences their political choice and what factors are most important when making a voting decision, 49% did not mention electoral platforms and promises (Figure 2)[17]. Indeed, this is a rather large figure and could explain why parties do not invest in developing comprehensive programmes. However, it is also worth noting that 34% of voters who consider that platforms are important is not an insignificant share. At the same time, as mentioned above, Georgian elections are not about policies but between “good guys” and “bad guys” who, in the end, might have rather similar policy positions.

What do the parties say about Green issues in 2024?

The present article is being written on the 2nd week of October and only 15 days before the crucial election day. As of now, several major parties, including the governing Georgian Dream and the biggest opposition party, Unity - National Movement (UNM), have not published their election programmes. Furthermore, the mentioned parties’ websites, which would be expected to outline main priorities, policies and positions, are defunct or have not been updated for months. Therefore, to understand parties’ positions on Green issues, we will look at some party programmes but since not everyone has them, we will draw positions using data aggregated by the Political Compass[18].

Strong Georgia[19]

The coalition[20] Strong Georgia is a merger of 4 political units. It is mainly based on social-liberal Lelo and includes two prominent figures leading their own parties - Ana Dolidze and Aleko Elisashvili, and the newly established Freedom Square, which has its roots in the NGO sector, led by Levan Tsutskiridze. The coalition has an extensive election program that spans 50 pages including 3 priorities, called Ilia’s Way, and is followed by an action plan entitled the Marshall Plan for Georgia. Its focuses on geopolitical (EU integration, protection from Russia) and socio-economic (pensions, reducing unemployment) issues. Green issues are mentioned as well. First, within the second priority on creating new jobs, it is underlined that the party will ensure compliance with EU’s Green construction standards and take into account environmental and public interests when approving large-scale infrastructure projects. In addition, the plan features the chapter “Environmental Protection, Climate Change, and Ecological Security”. It repeats the central points mentioned within the second priority and adds the promise to work towards reducing risks associated with environmental disasters. Importantly, it formulates the idea to (re)establish a separate Ministry of Environmental Protection and Resource Management, which has been merged with the Ministry of Agriculture.

For Georgia[21]

The party led by former Georgian Dream Prime Minister Giorgi Gakharia has recently repositioned itself as a centre-left force. It has an extensive programme titled the Manifesto for Dignified Living, which includes 30 pages, and a dozen subchapters followed by a more detailed action plan. The manifesto is comprehensive and includes policy positions on nearly all important issues spanning from healthcare, democracy, EU integration, culture, sport, and environment. As the name suggests, the primary focus is on socio-economic issues, building elements of a welfare state, including calls for minimum wage. As for the focus of our article, the manifesto has two subchapters: Energy and Development of the Green Economy, and Modernisation of the Mining Industry. The subsections are unusually detailed for the Georgian context. The party promises to incorporate a Green economy, promising to accelerate investment in renewable energy as well as Green start-ups and establish sustainable urban policy. It calls for institutional reforms to “ensure effectiveness”; this includes the re-creation of the Ministry of Environment, strengthening the role of municipal governments in decision-making processes, and plans to establish an environmental prosecutor’s office. The section also highlights the importance of climate protection and calls for policies directed towards energy efficiency as well as the revitalisation of the existing interagency climate change council to include ministers, MPs, and municipality representatives. The party devoted attention to the mining sector, but this section is less detailed. The party promises to change the mono-industrial development model of the industry, develop strategies to address ecological crises associated with mining and diversify the economy to reduce dependence on fossil resources.

Parties without published programmes

Georgian Dream

The governing party’s election campaign focus has been unusually devoid of any economic or social promises as it mostly revolves around notions of sovereignty, promises to ban the “collective UNM”, advancing a conservative agenda including further restrictions on LGBTQ rights, keeping peace with Russia and restoring Georgia’s territorial integrity through dialogue[22]. The electoral programme, presented by PM Kobakhidze on the 7th of October, has enriched the campaign with more social, economic and infrastructure-related promises[23]. However, we still do not have a written version of the programme available. Throughout the campaign period, there has been no mention of environmental and climate protection from the governing party. If we draw from the Political Compass data, Georgian Dream supports the proposition that businesses that pollute the environment should pay higher taxes, while the party opposes banning the construction of large HPPs due to environmental concerns.

Unity - National Movement (UNM)

The UNM coalition includes Strategy Aghmashenebeli, European Georgia, and several prominent public figures, and is still the main opposition party set to earn 2nd place. The coalition has focused its campaign on EU integration and its benefits, and socio-economic issues such as increasing pensions and reducing unemployment. It is important to note that, as we also see on the Compass, UNM policies, which were traditionally centre-right to almost libertarian have shifted leftwards in some areas such as support towards free school meals as well as gender quotas in party lists. Since there is no programme available, we can only use Election Compass to assess its positions towards climate and environment. The party disagrees that businesses that pollute the environment must pay extra taxes into the budget as UNM favours less regulation. Similarly, the UNM coalition opposes the ban on large HPPs.

Coalition for Change

Finally, Coalition for Change, which brings together former UNM leaders from the parties Ahali, Girchi, and Droa and has a more liberal outlook, is less focused on concrete policy proposals but rather on the overall need for changing the government, strengthening democratic institutions, need for coalition government and EU integration. The coalition recently published its manifesto, which is modest in size and content[24]. The manifesto has four priorities: Implementation of the Georgian Charter, Education, Economic and Regional Development; and includes promises to reduce taxes, strengthen municipal governance, make higher education free from 2028, increase budgets for primary and preventive healthcare as well as a gradual transition from public to private insurance. The manifesto does not address environmental or climate issues, although the mention of high-speed rail under regional development could be seen as a related point. Furthermore, according to the Political Compass, the coalition opposes banning the construction of HPPs, while there is divergence between parties regarding increasing taxes on polluters; Ahali supports this measure, while Girchi and Droa oppose it.

Conclusion

Environmental protection, climate, and energy policy are not important issues in the 2024 elections, and it is highly unlikely voters will choose a party based on their position on these topics. The tradition in which policies are secondary while personalities – decisive – continues. However, this election is also very different from anything Georgia has experienced previously. Voters will face one simple question at the ballot box: democracy or autocracy. The answer will have grave implications on the future of environmental and climate protection in Georgia.

If Georgian Dream manages to retain power, it will continue exploiting natural resources while completely disregarding environmental concerns. However, this time they may face no resistance from civil society groups or international organizations, nor any restrictions under agreements with the EU. Conversely, should the opposition win and form a coalition government, bringing Georgia back on path of democratisation and EU accession, it could have positive effects on climate and environmental protection over time.

First, the new government would be obliged to further harmonise with EU environmental and climate legislation, and as past experiences show, even if the government is reluctant, they still comply due to the significance of EU integration. Second, a change in government and perception of higher political freedom can create a more favourable environment for activism. Moreover, strengthening judicial independence and depoliticising institutions like the Ministry of Internal Affairs, as outlined in the Georgian Charter, would provide practical incentives for civic engagement.

Finally, I believe that in the future elections—perhaps for the first time in Georgia's electoral history —party programs will truly matter. People will be voting for a party not merely out of opposition to another, but because they genuinely support it. Voters will be choosing parties not just because a candidate is seen as a "good guy," but because the party's policies and platforms resonate with their values, needs, and positions.

The content of the article is the sole responsibility of the aurhot and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Heinrich Boelll Foundation Tbilisi Office - South Caucasus Region

[3] In this article, I focus on four opposition parties: United National Movement, Coalition for Change, Strong Georgia, and For Georgia. Other political forces are excluded due to their low likelihood of surpassing the 5% electoral threshold, as suggested by recent polling data.

[4]Georgian Charter: President Proposes Unified Goals for Short-Term Parliament, Technical Government – Civil Georgia

[6] პარტიამ „გახარია – საქართველოსთვის“ პრეზიდენტის „ქართულ ქარტიას“ ხელი მოაწერა – Civil Georgia; ზურაბ ჯაფარიძე - „ქართულ ქარტიაში“ გაწერილი რეფორმების ერთობლივად შესრულება ქვეყნისთვის პრინციპული და მნიშვნელოვანია | საინფორმაციო სააგენტო "ინტერპრესნიუსი" (interpressnews.ge)

[7]როგორ იყო ხუდონჰესის შემთხვევაში (radiotavisupleba.ge); ტრანსკავკასიური საუღელტეხილო რკინიგზა და წინააღმდეგობა საბჭოთა საქართველოში | ჰაინრიჰ ბიოლის ფონდის სამხრეთ კავკასიის რეგიონული ბიურო (boell.org)

[8] ბოკერია ნამახვანჰესზე: მოვუწოდებ გულწრფელ მოქალაქეებს, პარტიებს, არ შეუერთდეთ პროტესტს - ტაბულა (tabula.ge)

[9] "გასცდა თვითორგანიზებულ პროტესტს, საფრთხე შეუქმნა ენერგოუსაფრთხოებას" – სუს-ი ნამახვანზე - ტაბულა (tabula.ge)

[10] ხაზარაძე ნამახვანჰესზე: დისკუსია, უნდა აშენდეს თუ არა, უნდა შევწყვიტოთ – პასუხია კი! - ტაბულა (tabula.ge); მელია ნამახვანზე: დროდადრო მათი გზავნილი გაიბლარა - ტაბულა (tabula.ge)

[11] გომელაური ნამახვანჰესზე: სპეცრაზმს შეუძლია გამოიყენოს წყლის ჭავლი ძალადობის შემთხვევაში - ტაბულა (tabula.ge)

[15] Such as the Shovi landslide and Borjomi wildfires

[17] ‘ISFED: Survey on Election-Related Processes, 2021’. Accessed 11 October 2024. https://caucasusbarometer.org/en/is2021ge/ELIMPELP/.

[20] Although Georgia’s electoral code does not permit coalitions and blocs—meaning that these “coalitions” are effectively mergers into a single party—these groups continue to present themselves as coalitions. Therefore, we will use the term “coalition” and “party” interchangeably.