Anti-LGBTQ+ rhetoric has been a central element of the Georgian Dream’s anti-democratic turn towards the far right. How do anti-LGBTQ+ statements and policies help GD expand its grip on power, and why does this strategy work?

Introduction

The anti-democratic turn of the Georgian Dream (GD) has attracted a lot of attention in the past few years. Initially coming to power on a self-declared center-left platform, the party has done a complete ideological U-turn, coopting local and international far-right ideologies. A central element of this turn has been anti-LGBTQ+ rhetoric, increasingly present in the discourse of GD leaders. This change opposes the party’s early rhetoric and policies and solidifies GD as a far-right party itself.

How do anti-LGBTQ+ statements and policies help GD expand its grip on power, and why does this strategy work? In its 12 years as a governing party, GD has learned that coopting far-right ideas can be an effective way to avoid accountability and mobilize public support. This strategy works in two stages: first comes the party’s claim that it represents the “people” and protects them from “enemies” who are blamed for any political, social, or economic problems in society. Second is the consolidation of power justified by this supposed protection. In this process, GD simplifies complex issues, shifts responsibility for solving problems, and ultimately, centralizes and consolidates political power.

Defining “The People:” Nativism and the Far Right

In its anti-democratic turn, the GD follows a tried-and-true blueprint from far-right parties in Europe and beyond. Since WWII and the Holocaust, far-right parties have been trying to salvage their reputation by rebranding trying to distance themselves from the Nazi party and appear more moderate. A key part of this process is the use of democracy and human rights language to obscure the inherently anti-democratic nature of far-right ideology. A democratic government is one that represents the people; accordingly, a common strategy has been to redefine “the people” itself and then claim legitimacy by supposedly representing popular interests.

This strategy rests on nativist ideology, a core component of the far-right. Nativism is a form of nationalism that divides society into two groups: the “people,” or “us” that belong in society versus the “enemies,” or “them,” that do not. Far-right ideology presents both groups as homogeneous and inherently opposed to one another, and then claims to represent the “people,” prioritizing their rights and protecting them from the “enemies.”

The far-right division between the two groups is inherently fluid, and can take many forms, depending on context. It can be based on different components that make up one’s identity, like gender, sexuality, religion, ethnicity, and so on, whereas everyone beyond the narrow definition of the “people” is to be considered as foreign to the nation, someone who does not belong. The exact definitions of these groups depend on the issues that are most salient in each country context. So, the far right may emphasize some personal characteristics over others and combine them in different ways. For the Indian far-right movement “Hindutva”, it is the Hindus versus Muslims, for the Ukrainian far-right, anti-Russians opposing pro-Russians; for the Hungarian far-right, ethnic Hungarians against the Roma; for the German far-right, white Germans versus Muslim immigrants; for the Russian far-right, Russians against “the West.” For the Georgian far-right, the two groups are heterosexual Georgians and LGBTQ+ people.

Regardless of contextual differences, far-right ideology usually emphasizes traditional gender roles and heterosexuality. In it, the family – defined narrowly as a father, mother, and their children – is seen as a cornerstone for the stability and continuation of the nation, or the “people.” Thus, everything and everyone going beyond this narrow definition – a gay couple, a trans person, a woman deciding not to have children, a working mother – are considered foreign, as they threaten the vision of a homogeneous, ever-multiplying nation. This is why far-right movements worldwide have rallied against LGBTQ+ rights, abortion, and feminism.

“The People” in the Georgian Context

For the Georgian far right, “the people” has mostly meant cisgenders, heterosexuals, ethnic Georgians and Orthodox Christians, those with a heteronormative family and children. While these identity markers are often fused together in a perfect example of someone belonging to “us,” in the past few years, gender and sexuality have become more and more central for the Georgian far right. For more than a decade, far-right groups in Georgia have mobilized to allegedly protect (heterosexual) families and their children from LGBTQ+ people who are defined as a threat.

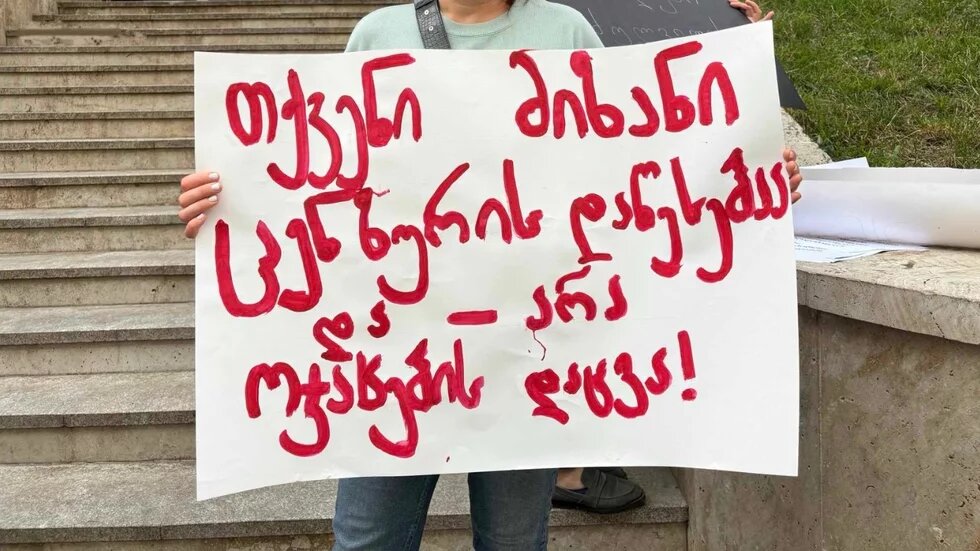

As a result, anti-LGBTQ+ protest has been the issue that mobilizes the Georgian far-right most often. The most infamous example was May 17, 2013, when thousands of protesters attacked a small group of activists celebrating the International Day against Homophobia and Transphobia. Anti-LGBTQ+ protest have also targeted other events organized by human rights and Pride groups, such as movie screenings and festivals, and even the display of a rainbow flag outside the Tbilisi Pride office. Far-right activists have also attacked those they perceived as LGBTQ+ allies, for example, football player Guram Kashia, who wore a rainbow armband during a match abroad when he played for a Dutch football club.

The rise in anti-LGBTQ+ mobilization in the Georgian far right has made LGBTQ+ people an attractive scapegoat for GD. In its 12 years in office, the party has learned that coopting anti-LGBTQ+ ideas from the far right can be an effective way to avoid accountability and mobilize public support.

As a result, GD gradually coopted the far-right definition of “the people.” Thus, the term came to represent heterosexual families with children. Anyone beyond this group is presented as an enemy. In addition to LGBTQ+ individuals, this includes everyone who supports LGBTQ+ equality, or even more generally, criticizes GD.

Nativism in Words and Action

Over the years, GD has been one of the parties in Georgia using homophobic hate speech most often, coming second after openly far-right parties like the Alliance of Patriots and Conservative Movement. In anticipation of Tbilisi Pride in 2019, for instance, a GD member warned that “the Georgian people” would never allow a Pride march. In 2021, then-PM Irakli Gharibashvili argued that holding a Pride event was “unreasonable” because “the people” were against it. Speaking at the Conservative Political Action Conference in 2023, then-PM also pledged to “protect the rights of the majority who believe in the definition of marriage as the union between a man and a woman” against those who promote “LGBT propaganda.” In statements like this, heterosexual families are presented as the majority, “the people” that GD claims to represent and protect – a definition that inherently excludes LGBTQ+ people and presents them as enemies. The rights of families on one hand and LGBTQ+ people on the other are presented as a zero-sum game.

The nativist turn of GD is also visible in legislative initiatives spearheaded by the party. As early as in 2017, the GD-majority parliament effectively banned same-sex marriage by changing the definition of marriage in the constitution (even though same-sex marriages were never legal in the first place). Finally, in 2024, the party delivered the most explicit blow to LGBTQ+ equality by adopting the law “on family values and protection of minors,” effectively banning adoption by same-sex couples, gender-affirming care, and depictions of LGBTQ+ people in media.

Protecting “The People”

The nativist division between “the people” and their “enemies” has been an effective strategy for not only far-right parties, but also mainstream parties worldwide who have shifted to the right to steal potential supporters from the far right. Examples include countries like Poland, Hungary, Turkey, Brazil, and Russia, where far-right ideas have helped incumbents stay in power and consolidate it even further. In the far-right blueprint that GD is now adopting, the strategy of defining and blaming “enemies” is effective because it achieves three interrelated goals: problem simplification, shift of responsibility, and consolidation of power.

Simplification

By dividing society into “the people” and the “enemies,” far-right actors can simplify complex political, economic, and social issues. For GD, the root cause of every issue in society essentially boils down to the “enemies,” defined as LGBTQ+ people and their supporters. Creating such an enemy image allows GD to shift focus away from the actual grievances of Georgian society, most of which are rooted in economic issues. As public opinion polls show year after year, the Georgian population is mostly worried about poverty, unemployment and ever-rising prices. Georgian households struggle to make ends meet, almost half of the population lives in debt, and nearly 90% has no savings. In GD’s far-right rhetoric, these economic problems are simplified and externalized, overshadowed by an alleged threat from “enemies” to “the people.” Thus, GD is able to ignore actual problems that persist in the very families it is claiming to protect: in Georgia, violenceagainst women is widespread, while children have been subject to early marriage, abuse, and pedophilia in spaces that include the Georgian Orthodox Church. In this context, fighting LGBTQ+ causes serves to shift public focus from actual societal grievances and simplify complex problems that need government attention.

Shift of Responsibility

At the same time, identifying a specific enemy helps GD avoid responsibility and accountability. Complex societal problems need complex solutions, whereas specific “enemies” can be “fought” by relatively simple means. Taking steps against what it calls “LGBT propaganda” allows GD to avoid accountability in tackling the economic grievances taking a toll on much of the population. Instead, it can claim to protect the in-group, “the people,” from perceived threats from the out-group, the “enemies,” through measures like the anti-LGBTQ+ law. Finally, a shift to the far-right also helps GD achieve its principal goal: maintaining and consolidating political power. In addition to nativism, a fundamental component of far-right ideology is authoritarianism, a firm belief in law and order, with an emphasis on authority and hierarchy. From an authoritarian point of view, any deviation from what is considered “the norm” should be strictly punished. This may include emphasis on strong leadership, as well as the punishment of transgressions on authority, especially when it comes to the “enemies.”

Consolidation of Power

By dividing society, GD can not only simplify complex problems and avoid responsibility for them but also consolidate more power in its hands in the name of “the people,” while claiming democratic legitimacy. Thus, the list of “enemies” includes not only LGBTQ+ individuals and their allies, but everyone that opposes GD or disagrees with it. This is not new: over its years in power, GD has regularly tried to frame its opponents in LGBTQ+ terms (in its most offensive and derogatory form – calling them “pederasts”): protesters against the violent police crackdown on Bassiani nightclub in 2018, protesters against Sergey Gavrilov (a Communist Party member of the Russian Duma who sat in a chair reserved by protocol for the Chairperson of Parliament) in 2019, protesters against election results in 2020, those protesting GD’s reluctance to secure Tbilisi Pride in 2021, those against GD’s stance on the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, critics of the foreign agent law in 2023, and finally, people protesting against election fraud in 2024-2025.

Nativism as a strategic move

Thus, GD’s turn to the right is more of a strategic move than an ideological one. Its aim is to simplify problems, avoid responsibility and, ultimately, maintain and consolidate political power. As the newly adopted draconian limitations on protest make clear, the party intends to repress and silence dissenting voices, ultimately framing them as “enemies” that “the people” need to be protected from at all costs. This stance, presenting pro-Russian and pro-LGBTQ+ positions as a binary choice, was inadvertently captured by the response that Zviad Kharazishvili, the Director of the Georgian MIA’s Department of Special Tasks, gave to a journalist asking whether GD was conceding to Russia: “What, should we concede to ‘pederasts’[1] instead?”[2]

The Content of the article is the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Heinrich Boell Foundation Tbilisi Office - South Caucasus Region

[1] “Pederast” is a derogatory reference to a homosexual person.

[2] @Georgia is Europe (2024), YouTube, Available from: https://www.youtube.com/shorts/NwBNWs_9Nr8.