This article discusses several key policy features relating to ethnic and religious minorities thirty years after Georgia’s independence. Some of the central questions explored in this paper include how the state has responded to the significant socio-cultural transformation that has taken place among different ethnic groups, and how the government’s policy towards religious minorities has essentially replicated the Soviet policy on religions, which was manifested in the supervision of religions by the state. To some degree, the state’s policy is a reflection of Christian-Georgian normativity, which only hinders society’s recognition of minorities as equal citizens.

Introduction - Nowruz lesson

In 2020-2021, several incidents occurred that dramatically underscored the state’s controversial policy towards national minorities[i], along with the dangerous effects of Christian normativity within society, and the xenophobia nurtured by it. We cannot say that this is entirely new. However, the pandemic seems to have exposed the state’s religious non-neutrality beyond the rights guaranteed by the constitution. It has also laid bare the shortcomings of its policy on civil integration.

Imagine that at the government’s initiative, Nowruz was declared a public holiday in Georgia. At first, we might view this initiative with skepticism, attributing it to populist politics in an effort to win the hearts of minorities – especially if it happened during the lead up to an election. In reality, everything happened differently. In February 2021, civil activists within Georgia’s Azerbaijani community filed a petition demanding that Nowruz be declared a national holiday. The argumentation of the request is especially important: “For many years, there has been no integration policy implemented in Georgia that makes the ethnic minorities in this country feel like full-fledged citizens of Georgia. Representatives of various ethnic minorities living in Georgia consider Georgia as their homeland, but their participation in the political and cultural life of the country is almost invisible. [...] Nowruz has a long history. It is also mentioned in Shota Rustaveli’s 12th century masterpiece ‘Knight in the Panther Skin’. We think this holiday will bring us even closer to the different ethnic groups living in our common family in Georgia. We value the fact that the petition is signed not only by ethnic Azerbaijanis living in Georgia but also by Georgians and Armenians,” noted Samira Bairamova, a civil activist and one of the authors of the petition.[ii]

It seems that this should be the goal of the state’s integration policy, which is mentioned in the petition and for which it was prepared. In addition, according to the State Strategy for Civic Equality and Integration 2021-2030: “Civic integration means the inclusion of all citizens of various ethnic identities living in the country in a multi-ethnic society, which includes their activity in public and political life, the formation of a strong, positive emotional connection with the state, and the creation and strengthening of a sense of identity and belonging.”

In general, there is a mismatch between the government’s declared goals and real action, but here, another side of the problem can be seen. Initially, the government responded with indifference as it considered the initiative (it has no plans to discuss the initiative in the future either). In fact, the state did not see the new process taking place among ethnic Azerbaijanis (Georgia’s largest ethnic and religious community) when the community attempted to define its place in Georgia as a political entity by using its culture and traditions to find ways to coexist harmoniously with the dominant groups in Georgian society, rather than separate itself from the majority and isolate itself. In contrast, for years now there has been no effort made by the state to provide real protection or empowerment to minority culture. Instead, the government has offered official congratulations on the dates allotted on the calendar to celebrate minority holidays, or has staged carnivalesque events based on a dramaturgy elaborated through the Georgian gaze.[iii]

Another example of the fears and stereotypes rooted in society pertains to the Azerbaijani community in Georgia. It showed how Azerbaijanis living in the Kvemo Kartli region became “familiar strangers” in times of crisis. The non-recognition of minorities, which has become the norm in everyday life, was manifested in anger and disgust when during the first wave of the pandemic in March 2020, the coronavirus was confirmed in a 62-year-old ethnic Azerbaijani woman in Kvemo Kartli. Because epidemiologists found it challenging to identify the first source of infection, the government decided to declare the municipalities of Marneuli and Bolnisi (heavily populated by ethnic Azerbaijanis) a strict quarantine zone. A wave of hatred and xenophobia erupted on social media during the assessment of the case. The ethnization of attitudes became clear in numerous comments and discussions. Their ethnicity explained the “main” guilt of the Azerbaijani community in spreading the virus. At that time, another label was given to minorities – their perception as “guests”: “Let them leave Georgia. They have been doing nothing more than causing trouble to the country for a long time (…) why shouldn’t the Azerbaijani government take them away? Or let them [the Azerbaijani government] explain them [Azeri community in Georgia] and accept the care we give them!”[iv]

This encourages us to ask once again and with new urgency two important questions: Is the tolerance constantly emphasized in Georgia today an “optical illusion”? And after the systemic transformations that have taken place since independence, what exactly is the state policy towards ethnic and religious minorities?

Policy of errors

The pairing of ethnic and religious minorities in the article is not accidental. Indeed, the history of each ethnic group and religious minority, the degree of their integration, and their challenges, are all different. Yet they are united by the same policy on the part of the state – control or indifference. It is also a common experience for the majority to perceive them as unequal and to be overshadowed by Christian-Georgian supremacy. Supremacy is everywhere – in language, calendars, textbooks, and even in street names. Of course, this is not unique to Georgian society. However, soon after Georgia gained independence, the issue of understanding these issues and uniting minorities in a common cultural and political space was not on the agenda. On the contrary, ethno-religious nationalism began to grow and strengthen in the country. The situation of minorities is determined not only by legal guarantees but also (and perhaps more so) by a consolidated view of who belongs to the Georgian nation. Framing the Georgian identity has been interrupted many times over the last two centuries, and each time it has been shaped by a new political situation. In the most recent historical period under the Soviet system, the status of a titular nation and the “encouragement of nationalism” gave rise to the ideological formation of the cultural “uniqueness” of the Georgian nation. The culture of the titular nation, along with Soviet supranational ideology, both served to overshadow ethnic diversity in the country. As for religion, the Soviet policies of both militant and forced secularism significantly changed the religious environment in Georgia. This started with the anti-religious policies of the 1920s, then with the so-called “taming of religions” (putting them in the service of Soviet rule under Josef Stalin), and ending with constant control of religions. Against this background, knowledge, perception, and, of course, the representation of religious diversity has completely faded. Georgia went beyond one of the most critical processes in the 20th century: the political, cultural, and legal understanding of religious diversity in modern society, the discussion of “minorities” as a new political idea, and their reflection into laws.[v]

Therefore, for the first time since independence, the Georgian state has to realize the majority-minority binarity of the nation-state, the “newly discovered” religious pluralism, ethnic diversity, and the need to maintain political unity. Many scholars believe that since the 1990s, ethnic nationalism in Georgia has been stronger than civic nationalism. Ethnic nationalism in the form of the culture of Georgian exclusivity and reverence to national pride can be seen as a reaction to the post-Soviet transition period. However, as noted, it is more appropriate to trace its roots to the Soviet or earlier historical period.

Ignorance or a lack of knowledge of historical experience often contributes to the easy creation of stereotypes, as well as baseless accusations made towards minorities. A large segment of contemporary society is unaware of the inherited barriers that hinder the political and social integration of minorities. For example, one does not know the (Soviet) historical-political and structural reasons why so many Armenians and Azerbaijanis living in Georgia do not speak Georgian today. In fact, during Soviet times, minority communities received their secondary education in their mother tongue, while learning Russian as the state language. The strategic rethinking of the political integration of ethnic minorities came late in post-independence politics. And yet, it should be noted that it was essential to introduce teaching Georgian as a second language after the Rose Revolution and launching the so-called 1 + 4 program in 2010. Thus, the representatives of ethnic minorities are given the opportunity to receive education in higher education institutions of Georgia in a simplified manner.[vi] The “Preferential Policy” increases the enrollment numbers in Georgian universities along with Georgian language proficiency.[vii] Meanwhile, the policy of teaching Georgian as a second language continues with inertia today. However, we can not say that it has entered a new stage or that the Georgian language can be mastered in regional schools populated by ethnic minorities.[viii] In addition, minority integration challenges are often reduced to the knowledge of the state language, and a number of other issues are completely ignored, such as the stigmatization of minorities, their disengagement from political and public life, and the lack of proper focus on minority issues. In the latter case, there is a danger that their cultural traditions, and native languages (e.g., Avars, Laijs, Tats, Udis) will weaken and disappear. The State Strategy for Civic Equality and Integration rightly mentions the need to protect and promote the cultural heritage of ethnic minorities. However, in reality, the political will to do so is very weak. This in turn, is a reflection of public attitudes. For example, the official website of the Autonomous Republic of Adjara, which describes the culture and religion of the region, does not say anything about the Muslims living there, nor does it say anything about the half-century-old wooden mosques that can be found in the region – some of which have been given the status of cultural heritage monuments. The sparse representation of various religious-cultural artifacts and traditions indicates that they are not perceived as part of the common Georgian cultural heritage.

As mentioned previously, the government did not consider it important enough to approve the initiative of the Azerbaijani community of Georgia in declaring Nowruz a national holiday. Further, the request of the community to cancel the pandemic-related curfew for one day to celebrate the holiday was not met.[ix] Were it not for the government’s different approach to minorities and the dominant religious (Orthodox Christians) group, this decision would have been considered a strict adherence to regulations. In fact, we witnessed tactical discrimination. Namely, the government had repeatedly lifted the restrictions imposed during the curfew on other occasions, including on a religious holiday, for example, when the Georgian Orthodox Church celebrated Easter.

Over the years, the state’s politics of indifference and error have been met with silence by the minority community, and have shaped the perception of minorities as a passive group. In recent years we have seen various communities trying to break through the closed circle and themselves give voice to the problems of their community. We observe such tendencies among the Kist community in the Pankisi Gorge, the Azerbaijanis of Georgia, and the Muslims of the Adjara region.[x] In 2018, the Kvemo Kartli municipality prepared a video of the region that did not include any pictures, symbols or cultural artifacts – things that would prove that Azerbaijanis live there.[xi] Such an expression of cultural dominance was followed by criticism from Azerbaijani community activists. In response, the municipality produced an alternative video showing the region’s heterogeneity.[xii]

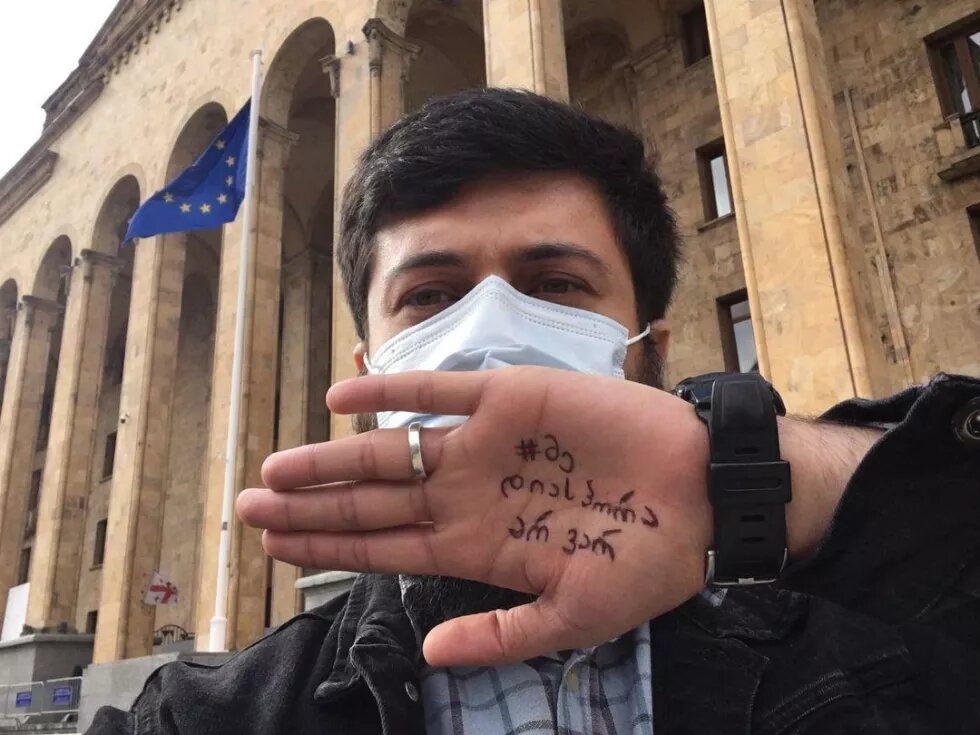

Another manifestation of the “error policy” was when on March 15, 2021, the Scientific Advisory Council for National Minorities was established based on the Committee on Diaspora and Caucasus Issues of the Parliament of Georgia. The existence of such a council in the legislature is welcome. However, its creation within the frames of the Committee on Diaspora Issues questions the topic of minority integration by the state.[xiii] This decision is a registration of the rhetoric and “temptations” that have been heard in recent times in the political space when Georgian citizens see ethnic minorities as having a stronger connection with another country than with Georgia. Representatives of the minority community and non-governmental organizations alike protested against the decision and held a small rally in front of the parliament building on March 18.[xiv] Defining the diaspora and national minorities as a “diaspora” undermines the integration process and strengthens the perception of minorities being “guests” in society.

State, Religious Minorities and the “Christmas Pass”

Certain rights and freedoms, including freedom of assembly, were restricted by the state of emergency declared by the decree of the President of Georgia on March 21, 2020. From April 17-27, 2020, driving was also prohibited due to the high risk of population mobility. However, the clergy, chanters, and chaplains of the Georgian Orthodox Church could travel by car to celebrate Orthodox Easter. The government did not provide such privileges to other religious organizations. A similar discriminatory approach was repeated on December 25, when a segment of Georgia’s Christian churches celebrated Christmas in 2020, and again when they celebrated Easter in 2021. Various religious organizations were forced to change the time and format of their feast and celebrations. For example, after a Christmas service was held at the Evangelical Baptist Church, parishioners stayed in the church until morning and waited there until the curfew expired. In comparison, the government lifted the restriction on movement on January 7 for the Orthodox Church. The Orthodox congregation was not required to meet any additional requirements for attending the service. Non-dominant religious organizations should apply to the State Agency for Religious Affairs for a one-time “Christmas pass,” and a list of parishioners and clergy members should be submitted.[xv] No less discriminatory was the justification of the privileges of the dominant religion by their personal religious views in this context. The incumbent Deputy Prime Minister Maia Tskitishvili explained the exception made to the restriction of movement for the Orthodox Church by saying that the majority of the population of Georgia is Orthodox.[xvi] The refusal of public officials to adhere to the principles of a secular state – at least formally – is symptomatic of today’s political discourse. It is also symptomatic of the establishment of the State Agency for Religious Affairs in 2014, reminding of the Council of Religious Affairs established during the Soviet era. Its mandate and official function was very similar with regard to its role as mediator between the government and religious organizations and the construction of religious buildings.[xvii] Later, it appeared that the agency also had an unofficial mandate similar to that of the Soviet-era Religious Council. Human rights organizations criticize the agency’s work because, in their estimation, it is in fact, the oversight body over religious minorities.[xviii]

Who defines “who belongs to the Georgian nation”?

State policy towards minorities in Georgia has one peculiarity: It is closely linked to the Georgian Orthodox Church. Ecclesiastical-religious discourse sets the tone for the rhetoric of social and political elites. The Georgian Orthodox Church and the national discourse nurtured it indirectly, but strongly formulate the view of “who belongs to the Georgian nation.” During the crisis of the post-Soviet transition, the church appeared in the people’s eyes as a counterweight to an unreliable political space. The tactical “political neutrality” of the patriarch of the Georgian Orthodox Church (GOC) turned out to be the desired mode for society. The myth of neutrality still works today, especially against the backdrop of weak state institutions and the weak concept of a civic nation. That is why the church still holds the “test of nationality.” If we recall the 1990s, the ecclesiastical discourse at that time defined the minority religions as “traditional” and “non-traditional”, and it was the GOC that judged their “credibility”: “It is time for everyone to realize the threat posed to our country by the raid of foreign religions and totalitarian sects. These years of experience have made it clear that they deny and insult our national feelings, our past, our history, and our sanctity, and lead thousands away from the path of truth, ” stated Patriarch Ilia II in the Christmas Epistle from 1998.

During the rule of President Eduard Shevardnadze, the state appeared to have ceded the issue of religious minorities to the church, whilst turning a blind eye to religious discrimination. During this period, defining Jehovah’s Witnesses and other Protestant denominations as a threat provided the green light for radical religious groups. At the same time, it strengthened the normativity of Orthodoxy within society.

However, after Shevardnadze resigned following the Rose Revolution, the integration of minorities gained the state’s importance for the first time. The new political team claimed that the ideas of civic nationalism had been the dominant voice in society, at least discursively. However, the legacy of the same period is the closeness of the state and the church and the protection of the idea of a secular state in such a way as long as the church allows the state to do so. With few exceptions, the state always considers the sentiments of the Orthodox Church and its faithful.

Consideration of the religious-national views of the dominant culture can also be seen in the case of the new mosque in Batumi. The local Muslim population has been demanding the construction of a new “Freedom Mosque” in Batumi for several years, and the legal dispute has been ongoing for more than four years.[xix] On May 5, 2017, City Hall rejected the application of the Batumi New Mosque Construction Fund to issue a permit for its construction.[xx] In 2019, the Batumi City Court found discrimination in the mosque case and annulled the decision made by City Hall rejecting the construction permit, which Batumi City Hall appealed. However, on April 14, 2021, the Kutaisi Court of Appeals upheld the decision. Muslims are still waiting for the execution of the court decision from City Hall.

During the 2021 local self-government election campaign, all Batumi mayoral candidates answered ambiguously when asked whether a mosque should be built in Batumi. Their response was that they would act within the law.[xxi] In this protracted and discriminatory process of building a mosque, we must see the great challenge religious diversity poses for Georgians, especially if it is visible in public. The unresolved problem of building a new mosque has become a symbol that reminds Georgia’s Muslims that it is their religion that is the cause of various social and cultural barriers. However, a notable trend that has emerged from the Batumi mosque saga is the fact that as a non-dominant religion, Islam is now entering the public space using human rights-based rhetoric. In the fight to build a mosque, Muslims are demanding the protection of religious principles and the principles of a democratic state. Unfortunately, each case of religious or ethnic harassment leads to a chain reaction, resulting in a common atmosphere of exclusion among minorities.

One of the manifestations of the state’s controversial religious policies and its failed attempts to overcome alienation, was a conflict that arose in January 2021 between the Muslim and Christian communities of the village of Buknari. The state responded to all disputes not by identifying the root of the problem accurately, or through strategic policy, or by undertaking structural changes, but by “intervening” and “restraining” through the actions of the State Security Service. In general, the use of security language in matters relating to religious and ethnic minorities and/or referring to citizens in the context of the interests of another state, completely distracts the state from the real problems and needs of the minority community.

Political participation of minorities

The political participation of minorities significantly determines the degree of social integration of minorities. In addition to making minorities feel part of one sovereign political body, they must participate in the institutional processes of democratic self-organization and policymaking. The participation of ethnic minorities in political life is weak in Georgia.[xxii] Barriers to this are complex and systemic. These include a lack of integration of minorities in various spheres of public life, language barriers, lack of political will,[xxiii] a distrust of state institutions, discreditation of political activism, lack of legal incentives by political parties to encourage an increase in the number of ethnic minority representatives in political parties,[xxiv] unhealthy electoral processes in regions densely populated by minorities, the controversial “involvement” of local elites (including clans and religious organizations) in the recruitment process by the government, and the lack of a vision on the party agenda for grooming professional politicians in the minority community.[xxv] The controversial influence of the ruling party and law enforcement agencies on voter behavior over the years, which is reflected in the ruling party’s support in minority regions, should be noted separately. One of the reasons for this loyalty is their feeling of being a “minority” and the desire to gain a sense of security.[xxvi]

A 2017 study by the Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Multiculturalism (CSEM) shows that ethnic minorities are underrepresented in the governance of municipalities that densely populated by ethnic minorities.[xxvii] Here we must pay attention to not only the numerical indicator, but also to the quality and context. Because the ethnic Armenian population in the Ninotsminda district forms an almost absolute majority, this figure contributes to the high share of minorities in public service.[xxviii] The meagre number of ethnic minorities in the parliament does not ensure their full political involvement. As past and present experience shows, the parliamentarian is not a representative of the virtual community, but instead, the most loyal person to the ruling party from the region who may not even know the state language. Such “political engagement” is criticized by active representatives of the minority community: “They [the ruling party] prefer to have people who do not know Georgian in the parliament and the Sakrebulo, and do not understand what is being talked about there and only know how to press the remote control button.”[xxix]

Conclusion

Modern society intends to maintain the existing identity patterns and finds it difficult to adapt to their revision. However, it does manage to resolve the issue of minority integration through political regulations and legal norms. A more complex process is cultural recognition. It is crucial that national minorities are not “skipped” in the modern narrative of the nation’s biography. In the case of Georgia, the roots of ethnic and religious diversity are in the past, and a shared history seems to create the foundation of an inclusive collective identity in the present. Indeed, we often cite examples of a culture of tolerance from the past. Yet today these examples are being transformed into a resource for touristic multiculturalism but are not being paired with human rights. Examples of tolerant culture from history are often used as an alibi for the facts of today’s discrimination.

So, the question remains: Is such tolerance an optical illusion which inaccurately depicts past images (including the more important ones that are a matter of pride) while also obscuring reality in the present? If we describe the current minority politics in two words, it is control and indifference: the oversight of religious organizations and the ignorance of the significant socio-cultural transformations and needs of various ethnic groups. The shortcomings of the current policy are in line with the ethno-religious nationalist sentiments within society, which in turn, is strengthened and supported by the Georgian Orthodox Church.

Of course, it is a great challenge for all societies to overcome the normativity of a dominant culture or race. But developing an integration strategy on one hand and promoting ethnic or religious superiority on the other is a policy that is doomed to fail. Enhanced ethnic nationalism in the post-Soviet period undermines the perception of minorities as equal citizens and as a part of one sovereign political body. Here it is worth mentioning that the establishment of such political unity is at a standstill today. Thirty years after independence there is a strong, developed, pluralistic civil society, which includes the participation of minorities, where civic values are formed. However, civil society has so far failed to force the state to commit to these values.

The content of this article is the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Heinrich Boell Foundation Tbilisi Office - South Caucasus Region

[i] The term "national minority" is a disputable but still accepted concept, which is loaded with political and legal content. It refers to various ethnic, linguistic, religious, and cultural groups living within the political boundaries of the nation-state. The text uses "ethnic minority" and "religious minority" to highlight the problems of a particular minority group.

[ii] “Citizens petition to declare Nowruz a national holiday”, Netgazeti, 2.03.2021, https://batumelebi.netgazeti.ge/news/331791/ (last access 28.09.21)

[iii] Tsotne Tskhvediani: “Nowruz - Do not forget the spring!”, Center for Social Justice, 21.03.2019, https://socialjustice.org.ge/ka/products/novruzi-ar-dagavitsqdes-gazafkhuli

[iv] A new symptom of coronavirus - xenophobia, 25.03.2020, https://www.marneulifm.ge/am/component/content/article/127-marneuli/28034-koronavirusis-akhali-simptomi-qsenofobia (last access 28.09.21)

[v] Carole Fink: “The League of Nations and the Minorities Question,” World Affairs, Vol. 157, no. 4, 1995, 197-205.

[vi] The simplified system provides for passing the general skills test in Armenian, Azerbaijani, Abkhazian, Ossetian languages and the possibility of obtaining higher education in case of accumulating appropriate grades. The young people take a training course in Georgian language for 1 year and in case of accumulating 60 credits, they continue their studies at the department of their choice.

[vii] Shalva Tabatadze / Natia Gorgadze: Study on the Effectiveness of a One-Year Georgian Language Training Program, Center for Civic Integration and Interethnic Relations (CCIIR), 2016, https://cciir.ge/images/pdf/CCIIR research document.pdf (last access 28.09.21)

[viii] Mariam Dalakishvili / Nino Eremashvili: Systemic Challenges of Education Policy towards Ethnic Minorities, Center for Social Justice, 2020.

[ix] The government did not heed the same call of the Public Defender.

[x] Sophie Zviadadze: Many Faces of Islam in Post-Soviet Georgia – Faith, Identity and Politics, in: Egdūnas Račius/Galina M. Yemelianova (eds.): Muslims of Post-Communist Eurasia, Routledge: London, (forthcoming in 2022).

[xi] Ethnic Azerbaijanis are the largest ethnic minority group in Georgia (6.3%). Most of them live compactly in Kvemo Kartli. Georgians and Armenians also live in the region.

[xii] “Image clip of Kvemo Kartli from the province with only Christian monuments”, Netgazeti, http://netgazeti.ge/news/291333 (last access 28.09.21)

[xiii] The council was formed without the extensive involvement of representatives of ethnic minorities and human rights organizations. The same thing happened in July 2021, when the Office of the State Minister of Georgia for Reconciliation and Civic Equality adopted the State Strategy and Action Plan for Civic Equality and Integration for 2021-2030. Leading organizations working on minority issues, active representatives of the minority community were not invited at the presentation.

[xiv] “There was a protest against the establishment of a minority council in the parliament under the Diaspora Committee” civil.ge, 18/03/2021, https://civil.ge/ka/archives/407035 (last access 28.09.21)

[xv] Permits issued to non-dominant religious groups were limited, and in many cases only one permit was issued per religious organization, “Freedom of Religion and Belief in Georgia in and Out of the Pandemic 2020-2021 (May)”, Institute for Tolerance and Diversity (TDI), 2021.

[xvi] “Maia Tskitishvili - the government ensures the protection of the rights of all denominations” 27.11.2020, https://bit.ly/2RbFt0b (last access 28.09.21)

[xvii] Otto Luchterhandt: The Council for Religious Affairs, in: Ramet, Sabrina P.(ed.) Religious Policy in the Soviet Union. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993, 55-83.

[xviii] “Non-Governmental Organizations on the Abolition of the Agency for Religious Affairs” http://tdi.omedialab.com/ge/statement/arasamtavroboebi-religiis-sakitxta-saagentos-gaukmebis-shesaxeb (last access 28.09.21)

[xix] According to the latest census of 2014, there are 182,041 Orthodox and 132,852 Muslims living in the Adjara region. 105,004 out of 152,839 citizens living in Batumi are Orthodox, 38,762 are Muslim.

[xx] The Muslim community collected the signatures of more than 12,000 citizens in 2016 and appealed to local and central authorities to allocate land for the mosque.

[xxi] “New Mosque in Batumi – What do think the mayoral candidates, Batumelebi, 10.09.2021, https://batumelebi.netgazeti.ge/news/364096/?fbclid=IwAR1UthmvL9jTHWZzZ… (last access 28.09.21)

[xxii] Levan Kakhishvili: Competition for Ethnic Minority Votes in Georgia: 2017 Local Elections, Policy Essay, Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Multiculturalism (CSEM), 2018.

[xxiii] Kristine Margvelashvili / Ani Tsiklauri: Electoral Systems and National Minorities, Integration of National Minorities in Georgia, Policy Essays, Netherlands Institute for Multiparty Democracy (NIMD), Office of the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities (OSCE-HCNM), 2017, 9-48.

[xxiv]CSEM 2018.

[xxv] CSEM 2018.

[xxvi] According to the CSEM survey, the electoral behavior of ethnic minorities is gradually changing as observed at the parliamentary elections of 2016, 2012, 2008, and they mno longer support the ruling party on the same scale.

[xxvii] In municipalities where the share of ethnic minorities is more than of ethnic Georgians (Gardabani, Marneuli, Bolnisi, Dmanisi, Tsalka, Akhalkalaki, Akhaltsikhe, Ninotsminda), we have the following statistics: 779 ethnic Georgians have one representative in the Sakrebulo, while 1,116 ethnic Armenians and 2,945 ethnic Azeris have one representative each. See information about the representatives of national minorities in the Parliament: http://csem.ge/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Infographics_minorities-in-parliament_Geo.pdf (last access 28.09.21)

[xxviii] After the 2020 elections, 6 MPs from ethnic minorities are represented in the parliament. In 2016, their number was 11, in 2012 - 8.

[xxix] Sopho Zviadadze / Davit Jishkariani: Identity Problems in Kvemo Kartli Azerbaijanis and Its Political and Social Dimensions. Center for Social Justice, 2018.