The process of linguistic decolonization had intensified in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In the former Soviet states, this means a rejection of the Russian language in favour of their national languages. In many of these countries, linguistic nationalism has become part of the protest and struggle for a better (real or illusory) future. However, protest and linguistic nationalism are incompatible in Azerbaijan, where the colonial influence of the Russian language remains strong.

Too Close to Home

(Tbilisi, July 2023)

This text is taking its excruciating time, as if resisting to come out. Every thought that comes to mind seems too banal or dubious, every phrase sounds false and unconvincing. This is in part because much has already been said on the subject of the Russian language in this context. More so, because this topic is a personal one to me. Russian is my native language, although I am a pureblood Azerbaijani. My linguistic space plays an important role for me, as it does for every writer. It is, after all, sensible that those of us who write are usually represented by our language first, which often does not coincide with our ethnicity, place of birth or residence.

Take Franz Kafka for instance, a Jewish man born in the former Austria-Hungarian territories that are presently known as Czechia, who is before all else, a German-language (though not a German!) writer. It is unlikely that he would have stopped writing in German, even if he had lived until 1939 and fled the Holocaust to the United States, like many other Jewish people did.

Speaking of the German language. German is not Kafka’s language, or Goethe’s language. Neither is it Hitler’s language. English is not “the language of Shakespeare”. Or Hemingway. It isn’t the language of Trump. Likewise, Russian is not the language of Pushkin or the language of Putin. It isn’t exclusively the language of “great literature” or the language of Sovietization. These are languages that have been used by millions of different people for a multitude of purposes at different times. No language is intended specifically for enslavement nor the purpose of writing poetic masterpieces. Even if it is hard to admit and accept it now.

Thus I have a right to have a voice in these heated debates, even if only because I am, in fact, one of those very “victims of colonialism” whose welfare everyone cares so much about. Linguistic decolonization, first and foremost, concerns those like me - whose Russian happened to be their native language due to historic root causes beyond their control.

Perhaps it’s wrong but too late - fait accompli. I have never lamented my being Russolingual: it would be silly to feel bad that you naturally have free command of one of the most commonly known languages in the world. To be ashamed of your linguistic identity, which has nothing to do with your political identity, and to renounce it in favour of the current political climate would mean to once again be pawns in other people’s geopolitical games, allowing someone else to decide for you.

As luck would have it, one of the positions closest to mine on this subject did not come from some Yesenin scholar at the Sorbonne (I wonder, do such people actually exist?) but the former Minister of Internal Affairs of Ukraine, Arsen Avakov, an Armenian by birth and a self-proclaimed “Russolingual Ukrainian nationalist”. On the other hand, it sounds even more authoritative coming from a real Ukrainian nationalist who’s an ethnic Armenian, rather than from the mouth of a hypothetical Western professor…

... A year before the war, Avakov stated that “the Russian language does not belong to the Russian Federation” and that it’s “no trademark with exclusive rights of use”. He said it is time to rid Russia of its monopoly over the Russian language, instead of voluntarily giving it this monopoly. Regardless of my feelings about Avakov, I completely agree with him here.

. But even if it is not simply a trend, and linguistic nationalism and decolonization via the rejection of the imperial language can in some cases be actually constructive, necessary and meaningful, the notion is still not applicable to Azerbaijan today. The situation here has formed in such a way that any aspiration for development of society or country is incompatible with any type of nationalism, including the linguistic kind.

Making It [Among the People]

The core population of the village of Surakhani, 17 km away from Baku, are Tats - a Persian-speaking people who have lived in Azerbaijan since time immemorial and have almost fully assimilated. Nevertheless, some of them still remember their own language, Parsi. For one, the, 58-year old journalist Shahin Rzayev:

“We spoke Parsi at home but I studied Azerbaijani at school. Though, Russian was taught to us too, of course. Although I knew how to speak Russian already, before going to school: I watched cartoons, and my parents taught me. As a result all three of the languages are native to me. And I don’t understand those who boast about not knowing Russian. After all, clever people should not be boasting of not knowing or not wanting to know something. But, alas, there is such a tendency now”.

Recently, Shahin asked his mother why his parents tried so hard for him to learn Russian back then. “So he makes it among the people”, she answered. A similar principle drives Azerbaijani parents today, when they enrol their children in Russian-taught classes, or the “Russian sector” as it is known in Azerbaijan.

According to official statistics for 2023, about 160 thousand children receive education in the Russian language in Azerbaijan’s public school system. Not the highest number for a country of 10 million population, but one and a half times more than five years ago. This does not mean that they all perceive Russian as their native language (just as students of English-language schools do not turn into native English speakers), but it does confirm the growing demand for Russian-language education. The Russian sector is most usually the choice of monolingual Azerbaijani speaking families: they believe that Russian-language education is better. Plus, they might feel that knowledge of the Russian language will come in useful in life, so why shouldn’t the child learn at the expense of the state?

In real life, the quality of Russian-language education is inversely proportional to the number of people who seek it: there simply are not enough teachers for that many pupils.

“My daughter’s class has 48 people. What quality of education can you speak of when a teacher can’t spend at least a minute on each child? The government doesn’t close the Russian sector, but also doesn’t supply it with human resources. They simply left it to run itself. But the Russian sector does have its advantages. For example, there children aren’t forced to read aloud the verses in honour of Heydar Aliyev’s birthday, there isn’t that level of military and nationalist propaganda and drilling they get as in the Azeri sector”, says 45-year-old Samira Akhmedbeyli.

Bilingual nationalism

Samira doesn’t want her 8 year-old-daughter to grow up Russian-speaking. But even more so, she does not want the girl to become a nationalist. That is the significant difference of Azerbaijan from many of its post-soviet neighbours.

Perhaps the example of Belarus is most demonstrative in this sense. There, linguistic nationalism, just as nationalism at large is seen as part of standing up against authoritarianism.

In Azerbaijan, however, the concept “nationalism” and all its derivatives (“unity of the nation”, “national interest”, etc) carry negative connotations for the protest-motivated part of society. This is the result of deployment of these concepts by the regime as part of its militaristic propaganda and consolidation of power. Moreover, the mainstream traditional opposition has not gone too far from the government on this point.

“In fact, the regime has appropriated such concepts as “nationalism”, “national unity” and so forth. This is why, to be a dissident in Azerbaijan today means to protest any nationalism, including linguistic”, the historian Altay Goyushov explains.

In turn, being a Russolingual Azerbaijani often correlates with ardent nationalism and loyalty to the leadership (who by the way are also originally Russian-speaking).

If before the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War there was a common opinion that Russolingual Azerbaijanis “spat on their homeland” and were “fifth column” through and through, it became clear in September 2020 that it was not so. In everything to do with Nagorno-Karabakh on social networks, Azerbaijani Russian speakers have shown no less categorical and militaristic patriotism than Azerbaijani speakers. It is even possible to say that they stood at the forefront of the information warfare, since they could broadcast to a wider, foreign audience and debate Armenians, proving to one another, who is wrong here, employing a rich arsenal of Russian obscenities.

“I think that for many of them this was a method to, for once in ages, feel a part of society.

To prove to themselves and others: I am one us, I am a real Azerbaijani, even if I am Russian speaking”, suggests Orkhan Sultanov, the 31-year-old photographer who noticed the uptick in patriotism among his until recently largely apolitical friends since renewal of military operations in Nagorno-Karabakh.

Russian-language media in Azerbaijan are also almost fully pro-government and decidedly concerned with “national interests”, doing their part in state approved information warfare.

However, Pedagogic University lecturer Shalala Mamedova suggests that assumptions cannot be made based on media and social networks activity alone.

According to her personal observations, the majority of Russian-speaking Azerbaijanis - especially the senior and the middle generations, who had witnessed the period when Armenians still lived in Baku - neither supported the military solution to the conflict nor were overcome with Armenophobia. The caveat is that they prefer to keep their opinions to themselves:

“Everybody knows that the public space in Azerbaijan is kept under strict control and that expressing a position that contradicts the official position of the state is dangerous. This is why social networks are mostly full of “patriotic” posts and gratitude to the president. This concerns both Russian and Azerbaijan language users. Keeping in mind the existing censorship and self-censorship in the country, one can only guess society’s moods”.

Thus, authoritarianism and nationalism are bilingual in Azerbaijan .The language factor plays no major role in countering both, and division between “us and them” is rather principled on ideology, not lingual belonging.

Protest in Azerbaijani

Modern-day protest as envisioned by Azerbaijani independent groups and organisations, including the Baku Research Institute directed by Altay Goyushov, does not envision linguistic decolonization for decolonization’s sake. As they recognize the importance of Azerbaijani language for the developing society, they stand against counter-positioning it to any other language, its sacralization and equating its use to having a civic position. According to these organisations, the best that can be done for Azerbaijani, and with that, for the society at large, is creation of Azerbaijani content that advances the importance of democracy and anti-authoritarianism, including a critique of nationalism and a debunking of certain national myths. For example, in the summer of 2023, the publishing house Egalite had translated and published the British historian Eric Hobsbaw’s 1991 book “Nations and Nationalism after 1780”. The Baku Research Institute regularly publishes original and translated academic articles on topics that otherwise remain mainly untouched in the official information space.

But it is not only marginal dissidents who lament the absence of quality publications, and especially scientific materials, in Azerbaijani language. According to Shabkhaz Khudoglu, a most known publisher in the country, the 32 years of independence did not see the creation of a normal education system. Absence of quality textbooks in Azerbaijani means youth can only acquire a higher education if they have strong command of foreign languages - Russian, English, or Turkish.

No matter how hard one might try, these shortcomings cannot be written off to treachery of Russia, the West, Türkiye, masons or bad-wishers from outer space; this is an internal Azerbaijani problem, or to be more precise - a part of a complex problem.

Even the quality of translated popular fiction, says Khudoglu, who publishes such fiction - leaves much to be desired. The situation is confounded by the absence of professional literary translators or a teaching institution of creative translation as such.

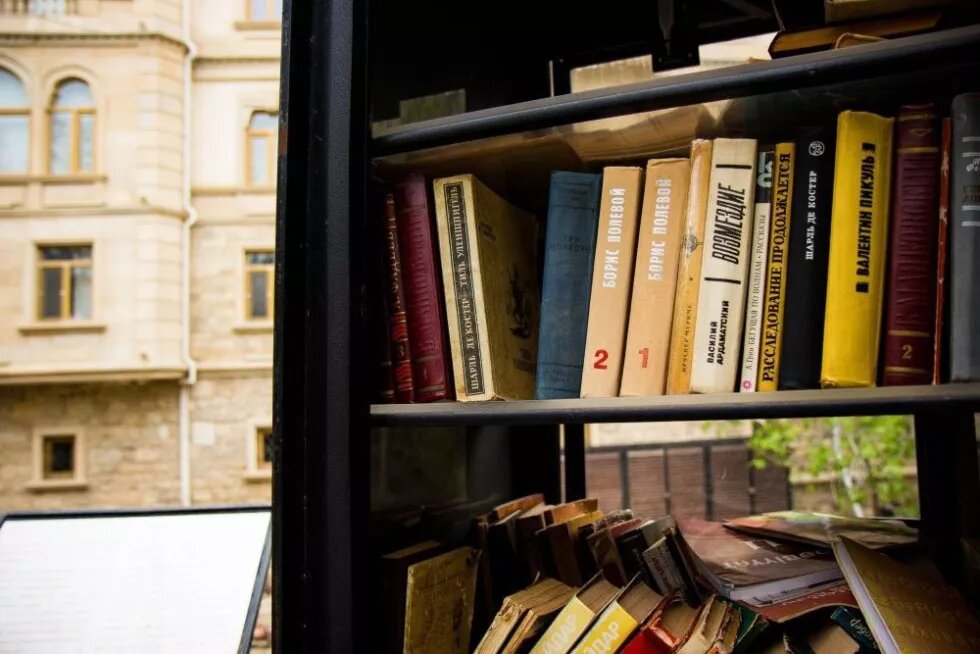

“In my childhood and youth even our village library had shelves overstocked with translated literature, and the quality of translation was good. But when Azerbaijan switched from Cyryllic to Latin in the early 1990s all these books were literally taken to the dump”, Shakhin Rzaev recalls.

Turkish Trace

The transition to the Latin script began after Azerbaijan acquired its independence in 1992, and took nearly ten years to complete. The generation that started school in that period had learned how to read in Latin but books printed in Latinic typeface would not appear. And even if they read in Cyrillic, they still ran up again a deficit of literature of any content, but especially scholarly books and journals. Those who still wished to read, watch and listen would get used to doing it in Turkish, and thus, grew up in a Turkish-language information space.

As a result some became adepts of Turkish pop-culture, others got into pan Turkism, and yet others were influenced by the leftist poet Nazim Khikmet and translations of Foucault and Marx. The second category excellently fits in the current situation: after all, Azerbaijani nationalism of today is clearly “Turkic''; the government and even to a greater degree, the opposition, use every opportunity to restate that Azerbaijanis and Turks are brothers, that we are of “same blood” and must keep together, and stand against foreigners and foes. Those in the third category, on the contrary, have turned into anti-nationalists of left or near left persuasion.

Meanwhile, Turkish language continues to influence daily speech of Azerbaijanis. I would add, it does so unnoticed by them, since the two languages are of the same linguistic family and are similar. Banovsha Mamedova, the Dean of the University of Foreign Languages and translator from Italian, notes that many of her students now and then use Turkish words, not even realising that they are Turkish and not Azerbaijani.

Unreliable Currency

“Literature, theatre - in this and many other fields, the “national” in Azerbaijan exists as a small island, cut off from the developed world. There are many talented young people, but they lag in their knowledge and values, since there are no Azerbaijani-language sources from which that knowledge and these values may be attained. It’s necessary to make all this accessible for those young people who don’t have a strong enough command of foreign languages,” says Altay Goyushov.

In recent years, an increasing number of young people (practically all of those with intellectual or financial abilities) leave Azerbaijan to complete their bachelor or graduate level studies abroad. Their destination: Europe, US or, in extreme cases, Türkiye. A significant number of them do not return to Azerbaijan as they find the best use of their foreign-earned degrees elsewhere.

Knowledge of foreign languages, Russian at least, is also needed to find good work inside the country. Though even that does not guarantee you employment. Being connected through friends and family ties is a much simpler and reliable option.

In this light, Azerbaijani language remains an “unreliable currency”, one that won’t “buy” you a good future nor help you “make it among the people”. But this obstacle is not even the main one on the path to sound standing of Azerbaijani language at least within its own borders.

Sociologist Samira Alakbarli reminds us that practically all languages that are nowadays referred to as “world languages” have attained that status precisely because they were initially colonial: “English, French, Spanish… All these languages spread around the world through colonial policies of their “state carriers”. And these very colonisation policies allowed these countries to accumulate enough resources for their development, making their languages attractive. They created socio-economic conditions in which learning of the imperial language was beneficial. Same nowadays, this most significant socio-economic factor can’t be ignored in the process of linguistic decolonization.”

****

(Tbilisi, September 2023).

This text took its excruciating time. It resisted. In the span of that time, came the “anti-terrorism operation” in Nagorno-Karabakh, and the arguments between Armenians and Azerbaijani’s on social media flared up again. They argue and curse and blame one another for all earthly sins again, mostly in Russian. To the majority of them, it remains the most comfortable lingua franca. They are using the language that was spoken relatively recently in the “international” Soviet Baku. Perhaps it would really be better if they had completely forgotten it after the fall of the USSR?

Irony would have it that eventually it will happen: they will forget it and likely only in 10-15 years new generations of Armenians and Azerbaijanis will befriend or curse one another in pure English. If, of course, they could still be friends, and not only quarrel. And if by then some historic events do not “devalue” English just as well.

P.S. Do you remember the legend about the tower of Babylon?... What if it was actually different, and it was not God who divided people, forcing them to speak in different languages and scatter in different directions, but it was them who began to use the only existing language at the time for quarrelling and mutual blame? So God was compelled to take measures to end this mess… It is since then that people keep searching for their lost common language.